This story is the last in a series, The Show Must Go On, examining who knew what, when, and what action they took when confronted with reports of sexual misconduct by Jeffrey Clayton and other teachers.

The series is based on tens of thousands of pages of public records and historical documents, as well as dozens of interviews with lawyers, local officials and current and former Douglas Anderson students, teachers and administrators.

Do we know there won’t be another Douglas Anderson scandal?

District administrators — including a new superintendent and new Douglas Anderson principal — say they’ve made “significant” changes to prevent sexual misconduct and ensure teacher misconduct reports are taken seriously. Parents of current students say they can see the results.

But some former students say they wonder if the changes will be enough to overcome what they see as a deeply ingrained power imbalance in performing arts culture.

The ‘transparent’ investigation

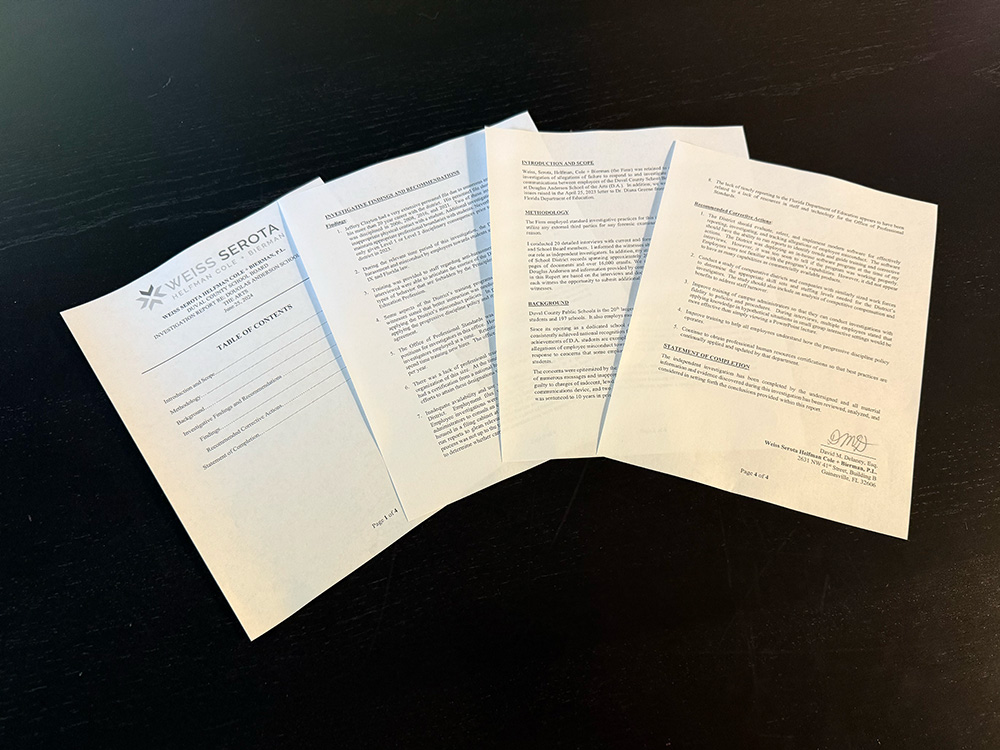

A month after Jeffrey Clayton’s arrest, the Duval School Board decided to spend $35,000 to retain an outside law firm to investigate “what happened” at Douglas Anderson, as well as what led to the district’s misconduct reporting issues.

Since that April 2023 meeting, the school board has said very little publicly about the independent investigation, and Duval Schools has yet to publish the resulting findings or alert parents to them — even though email records show the district received the firm’s final report in late June 2024.

At that 2023 meeting, city of Jacksonville attorney Jon Phillips promised the process would be “transparent.”

“Once the report is final, and we’ve had the opportunity to fix the problems, that report would become a public record so that anybody who wants to know what happened and who did what to who and and who’s been disciplined and who not — ultimately every bit of the investigation will be transparent,” Phillips said.

Records show Duval Schools has since paid at least $102,625.22 to Weiss, Serota, Helfman, Cole + Bierman — the firm it contracted to conduct the investigation — beginning in November 2023. The district says it can’t provide a detailed cost breakdown.

When Jacksonville Today first requested a copy of the report in early February 2025, both a district records custodian and the city of Jacksonville’s spokesperson said the requested record did not exist. Then, after Jacksonville Today received the report from two separate sources, the district produced it in mid-March.

The 1,095-word report is three pages long. And a table of contents.

In it, the firm says it interviewed 20 current and former district employees and reviewed thousands of pages of documents and more than 16,000 emails.

The conclusions? Duval Schools struggled with a “lack of clarity in applying the progressive discipline policy and its interplay with (faculty members’) collective bargaining agreement.” Also, the district’s professional standards office — tasked with investigating allegations of employee misconduct — was understaffed, and the office’s reliance upon paper records and a single spreadsheet was inadequate. The HR Department was also undertrained and underqualified.

Paying for it

Beyond the money paid to outside law firms to conduct reviews of its processes, the Duval School Board has so far approved more than $1.93 million to settle civil complaints with seven former students who accuse the district of mishandling reports of teacher misconduct at Douglas Anderson — most recently, an undisclosed amount they approved in July of 2025. None of the settlements admitted any wrongdoing.

Jacksonville Today requested all payments the district has made to settle litigation in the last five years. The district returned a list that did not include certain known cases and has yet to provide requested clarification.

Duval Schools currently faces at least four more similar complaints, according to Chris Moser, an attorney representing some of the accusers. In a text message to Jacksonville Today, she calls the settlements a “stark acknowledgment of systemic failures.”

“We remain cautiously optimistic that the district will finally commit to transparent practices and robust reforms that safeguard every child, rather than continuing to protect its reputation or bad actors,” Moser wrote.

What has changed?

“What is the district’s message to the D.A. community now?” Jacksonville Today asked. A Duval Schools spokesperson said, in the last year, the district has “significantly expanded” the training all staff receive on “ethics, reporting responsibilities, appropriate methods of communication with students, Title IX, and similar topics.”

Policies now require administrators to immediately remove employees alleged to have committed certain infractions — and employees who fail to report misconduct are themselves subject to discipline.

At a school board workshop this January, then-HR Director Vicki Schultz shared how the district has changed how it investigates allegations of employee misconduct.

A newly created committee evaluates all cases involving alleged child abuse, sexual misconduct, bodily harm or drugs — with representation from schools, the HR office, the district’s legal counsel, Duval County School Police and a few other departments. Investigators formerly managed each case solo, but it’s a group project now. The committee may choose to review other types of cases as well.

Schultz said the professional standards investigator presents cases to the committee, then leaves the room while they discuss. If they need more information, they can call the investigator back.

When school board members asked whether misconduct could continue to fly under the radar, Superintendent Christopher Bernier said he believes the committee approach will help prevent cases like some he’d seen — when an employee had multiple reprimands for similar offenses but was not progressed through the four official steps of discipline: verbal reprimand, written reprimand, suspension and termination.

“Discipline should be progressive,” Bernier said. “There are safeguards in place, but there is also an expectation in (the Office of) Professional Standards of ‘We just don’t keep telling people ‘don’t.’’ We move things up.”

Bernier is now expected to review the committee’s cases weekly instead of quarterly, as previous superintendents did. Jacksonville Today requested a sample of recent weekly reports given to Bernier. The district replied, “There are no records responsive to the timeframes specified. Please note that updates provided to the superintendent are communicated verbally.”

The district says it’s also erring on the side of caution when deciding what misconduct reports and incident reports are sent to the state.

“The superintendent’s preference for his team is to be asked to stop versus being required to bring more,” Bernier told the school board, talking about his own philosophy about submitting cases to the state for review.

Schultz told the board principals are also now required to notify HR of any planned employee transfers — whether between schools or between positions at the same school. Her office then reviews the candidate’s disciplinary record — including all reports of both substantiated and unsubstantiated claims.

“So even if you have five unsubstantiated [misconduct reports], and even if they’re from 20 years ago, you’re going to review them before you make a decision whether you want to move forward,” Schultz said.

Bernier said he put that procedure in place because he had “uncovered a couple of interesting situations” when an employee had transferred positions.

On her way out the door last summer, interim Superintendent Dana Kriznar published a 20-point plan to orient Duval Schools’ practices more toward student safety. Her plan, published the same week that the district received the independent investigation report, echoes the law firm’s recommendations. It’s unclear which document came first.

Last August, the district also rolled out a marketing campaign called “Know the Line,” which is designed “to help parents recognize the healthy boundaries that should exist between students and employees and how to report concerns,” says district spokesperson Laureen Ricks.

Staff must now limit physical contact with students to handshakes, high-fives and fistbumps, and they are allowed to communicate with students only through the district’s official channels.

Ricks says students can now report concerns about employees directly to the district through its website, too.

Virginia Commonwealth University sexual misconduct researcher Charol Shakeshaft compares misconduct complaints to fire alarms: Yes, there is a possibility that students would falsely accuse someone — or pull fire alarms as a prank — but, “We haven’t said, ‘Oh, kids pull the fire alarm. We’re not going to have any more fire drills…No, we have them! We should be doing the same thing with this kind of harm to kids.”

‘Culture that always needed to be at that school’

Today — just over one year after its most notorious teacher was sentenced to a decade behind bars — the district-level policy changes have some parents seeing a brighter future for the school, which hasn’t seen its enrollment drop any faster than the district as whole.

Eden is a second-generation Douglas Anderson student.

Her mom, Dallas Johns, says she’s talked with the rising sophomore, in broad terms, about why some teachers were removed from their classrooms. They’ve talked about healthy boundaries.

Johns, who graduated from the D.A. vocal program more than 20 years ago, says, despite the headlines of the past three years, it was an easy decision to send her daughter to the district’s flagship arts magnet.

Eden is a creative kid, Johns says, and she knows that having a creative outlet helps her academically. And so she sent her to D.A. as a freshman last year.

“I would worry about their safety the same way at almost any school,” Johns says of her two teenage daughters. “Stuff happens at a lot of schools — and it shouldn’t be happening — but it seems like [Douglas Anderson] has taken a bigger hit in the social eye than other schools have.”

Johns says she remembers that while she was a student at Douglas Anderson, Clayton once threw a conducting baton at her, prompting her dad to pay a visit to the school.

“It’s amazing to me that [Clayton] lasted that long at all,” Johns says. “If he had still been there, I don’t think I would have wanted my daughter to go there.”

But also, the school nurtured her creativity. Today, she owns two businesses — “creative businesses, and they have nothing to do with singing” — and she says the school gave her the confidence to build them.

Her new role as a Douglas Anderson parent gives her a front-row seat to the changes happening in the school’s post-Clayton years. New Principal Tim Feagins is working to take mental health more seriously, she notes. She says she’s noticed a “huge shift in professionalism” at the school, and Feagins is helping to create “the culture that always needed to be at that school.”

In February 2025, Feagins took the stage at the Jacksonville Center for the Performing Arts, addressing a packed house for Douglas Anderson’s Extravaganza, the school’s annual community showcase of students’ talent.

“Most of us say we have to go to work,” Feagins told the crowd. “I say I get to go to work.”

Feagins, who was just named the Florida PTA‘s Outstanding Administrator of the Year, is D.A.’s third principal since Jackie Cornelius retired in 2017.

Speaking to Jacksonville Today on the Friday before spring break, he gave a fast-paced tour around the campus, greeting students by name and offering fistbumps at every turn. Feagins’ own daughter started at Douglas Anderson as a freshman last year.

“The school has had some perception challenges lately because of — events,” Feagins says. “So how can we combat that?…We know what Douglas Anderson is, and because of some select individuals’ decisions, that doesn’t define who we are as a staff and faculty.”

D.A. is Feagins’ fourth principalship in the last 15 years. Before his transfer to the arts school, he was sent in 2019 to Riverside High — when it was still named for Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee — during a tumultuous period that included the school’s renaming and the district’s controversial disciplining of a teacher over displaying a Black Lives Matter flag. Coming into Douglas Anderson, as at Riverside, Feagins says he’s prioritized transparency with students and staff.

“They need to see those little things along the way — when they bring something up, that’s something’s being done. And, if we can’t do something, that actually I call them in and talk to them about why we couldn’t do those things,” Feagins says. “That transparency is extremely important — because once trust is broken, it’s very, very hard to regain that trust.”

Feagins had to send emails to Douglas Anderson parents twice during his first year at the arts school, announcing the removal of two teachers accused of misconduct. First, last August, he told them he’d removed Craig Leavitt from the classroom for “inappropriate communication with a student” two school years prior.

The principal told Jacksonville Today in March he never wants students or their families to suffer, “but also, the staff gets hurt too — because none of my staff here were responsible for what took place. But they still get the brunt of it, too, in a certain sense, because they come to work, and that name is still out there connected to what took place in the years past. So they’re overly cautious to make sure that policy, the underlying policy, is being followed.”

Then in April, he had to inform families that he’d removed another teacher amid allegations of “inappropriate conduct” during a previous school year. The district has yet to release details of the complaint against that part-time teacher.

Feagins says, while interviewing new hires, he asks teacher candidates not just about their arts acumen but their teaching style — like how they might react if a student misbehaves.

“That’s extremely important to me — that we’re not just looking at their ability; we’re looking at what can they actually do as a teacher, as well, in the classroom,” he says.

‘Casting couches’

While some alumni and current parents applaud the efforts of the district and Principal Feagins, some believe the efforts might be upstaged by an industry culture that goes far beyond the campus.

Douglas Anderson’s public reckoning with sexual misconduct in 2020 came amid a broader societal conversation about the entertainment industry. Harvey Weinstein and Jeffrey Epstein dominated headlines, and actors began to talk openly about “casting couches” — the idea that Hollywood and Broadway run on a system of abuse of power.

“Now does that mean it always has to be so?” asks one D.A. alum, who is in the process of suing the school district over alleged “sexual abuse” by ex-teacher Michael Higgins. “No, and there are certainly directors and people that are changing that. The casting couch is a thing of the past, but the fact of the matter is D.A. had casting couches…And the more you visited those couches, the more you got cast.”

Dani Burgess, who says she reported teacher Tim Kline for sexual misconduct in the early 2000s but saw no changes, agrees.

“I don’t know if D.A. can move past that until the industry does,” Burgess says. I appreciate this principal’s attempts,” Burgess says. “I really do. But we are not going to have healthy art academies without a healthy art industry. I just — it’s a lot more work than just getting the creeps out.”

Another former D.A. student, who settled a civil complaint with the district over her allegations against former film teacher Nicholas Serenati, pushes back on the idea that the people speaking up about D.A.’s problems in recent years are “disgruntled” and “want to see D.A. destroyed.”

“I want to see D.A. thrive. That’s the whole reason I’m talking about it — because if they can’t figure out whatever this stuff has been for decades, then I don’t know what they’re doing,” she says. “I love Douglas Anderson. I want to see it succeed. That’s why I think this is important.”

This story is fourth and final part in a series, The Show Must Go On, examining the handling of reports of teacher misconduct at Douglas Anderson School of the Arts — and what’s changed in the more than two years since Jeffrey Clayton’s arrest.