This story is the third in a series, The Show Must Go On, based on tens of thousands of pages of public records and historical documents, as well as dozens of interviews with lawyers, local officials and current and former Douglas Anderson students, parents, teachers and administrators.

Douglas Anderson School of the Arts is among the nation’s best public high schools.

Around 1,000 students — about three-quarters female — choose to attend the prestigious magnet school, which requires an audition for admission.

The school district touts Douglas Anderson’s academic prowess: A 100% graduation rate for four years running. Above-average SAT scores. Graduating classes who collectively earn tens of million in scholarships.

Douglas Anderson students shine brightly when it comes to the arts too. They have won national YoungArts awards (putting them in a club with Timothée Chalamet, among other past winners) and they’ve been nominated for Jimmy Awards (think Tonys, but for high schoolers). Grads have performed as Aaron Burr in Hamilton on Broadway, founded major touring music acts like Limp Bizkit, starred opposite Tom Cruise in movies and had parts on sitcoms like 30 Rock.

Others use the skills they learn about artistic expression to take center stage in courtrooms or classrooms or in boardrooms or aboard Navy submarines.

But in recent years, much of the local spotlight on the school has been focused on reports of teacher misconduct.

As students shared allegations online, in court and in news reports, the Douglas Anderson community found itself asking, Was Douglas Anderson really worse than the average school?

Did something about the school lead teachers to misbehave?

And, did being an arts school play a part?

Answers to these questions are hinted at in district records and in interviews with former students. At the same time, documented issues with Duval Schools’ incident reporting practices raise the question of whether accurate comparison is possible.

Was it just Douglas Anderson?

Jacksonville Today requested the state records of employee misconduct reports from 15 public arts schools in Florida over the last decade. That request has gone unfulfilled six months after Jacksonville Today paid for the records.

Employee misconduct reports from every Duval County public school, as tracked by the district, show Douglas Anderson historically has not stood out from the local pack when it comes to recorded complaints of all kinds.

Every investigation of misconduct was until very recently meant to be entered into a central digital spreadsheet in the district’s Office of Professional Standards, according to a 2023 state inspector general’s report that lambasted Duval’s reporting. Jacksonville Today combined several iterations of the master spreadsheet, received through public records requests, and totaled up 4,026 incidents of alleged employee misconduct of all types that were reported to Duval Schools between 1980 and 2022.

Of those allegations, Douglas Anderson reported a total of 32 over the roughly four decades, placing it in the middle of the pack among Duval’s high schools. First Coast, Ed White, Englewood, Sandalwood and Terry Parker each reported more than 50 incident investigations.

Search any school’s name to see its total reported incidents:

Among all misconduct reports, about half came from elementary schools. The school with the most investigated incidents was Arlington Middle with 80. Lake Shore Middle was second with 70.

When it comes to sexual misconduct allegations specifically: Just 4% of Duval’s high school investigations over the roughly 40-year period were classified as sexual misconduct (with labels like “sex” and “sexual” in the spreadsheet). Douglas Anderson was tied with Andrew Jackson and Fletcher high schools for the most reports — with three incidents apiece.

Tap on the chart to explore the outcomes of all misconduct investigations:

The employee misconduct report data are not complete, however.

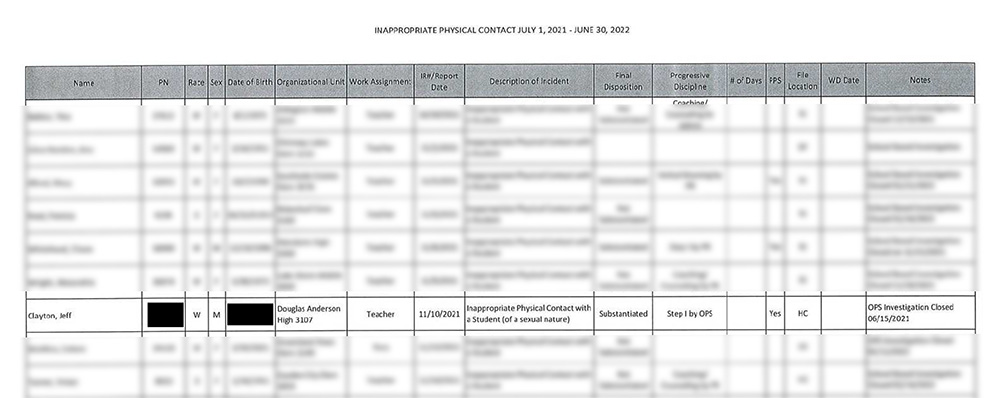

Duval Schools’ Office of Professional Standards processes more than 400 investigations annually, according to testimony to the inspector general’s office — but nowhere near that many appear in the compiled data. And a former district professional standards office employee who reviewed the data notes several memorable cases are missing. For one thing: Jeffrey Clayton is listed just twice, though he was investigated eight times during the timeframe, based on his personnel file.

Also missing from the spreadsheet is Douglas Anderson English teacher Kat Jackson, a non-arts faculty member who, in 2009, was prosecuted for a sexual relationship with a student. According to state Education Department documents, after finding an email from Jackson to her son, the boy’s mother reported her to then-Principal Jackie Cornelius. Jackson was arrested within days, pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 18 months in prison. She remains a registered sex offender, and her teaching license was permanently revoked.

When Jacksonville Today asked the district about the missing incidents, a records custodian said only that there are 5,291 entries in “the spreadsheet.” (They have not clarified whether that is the total through the current day.) A spokesperson did say a new electronic management system, which cost about $50,000, went live on June 16 — replacing the former system for tracking misconduct reports that was based on paper records and manual entry into the digital spreadsheet.

Of the more than 4,000 records available, nonetheless, there were 1,089 substantiated cases of “inappropriate communications,” “inappropriate physical contact” (which could include nonsexual physical abuse) and sexual misconduct districtwide.

D.A.’s three listed sexual misconduct investigations were Corey Thayer in 2015, Michael Higgins during the 2019-20 school year and Jeffrey Clayton in 2021. (Clayton’s investigation was the only one of the three that was substantiated.)

Labels aren’t necessarily consistently used across the spreadsheet either. A Clayton investigation in 2016, about his rubbing a girl’s shoulders and commenting on her appearance, was classified as “poor judgement.”

Categorized as “inappropriate communication” in the data was the case of D.A. social studies teacher John Vetsch. In September 2015, a student confided in another teacher that an “inappropriate relationship was developing between Mr. Vetsch” and a friend, according to Vetsch’s personnel file. The student shared screenshots of texts between Vetsch and her friend, which included this exchange:

“You sure looked nice in your black dress the other day, and I liked my hug. Hope I didn’t squeeze you too hard.”

“Thanks, I love dressing up and nah”

“I felt like my hand was on your butt and my face was in your chest!”

“But that’s because I was sitting down!”

“But I kind of liked it”

The teacher immediately — within minutes — contacted the student’s mother and reported the situation to then-Assistant Principal Melanie Hammer. Then-Principal Cornelius filed a report with the district the next day. Vetsch was fired within weeks, and the state permanently revoked his teaching license.

Duval’s reporting issues

Keeping misconduct reports organized at the district level hasn’t been Duval Schools’ only challenge. Data issues also extended to the district’s mandatory reporting of incidents to the state of Florida. Duval Schools’ reporting practices were under scrutiny in Tallahassee before Clayton was arrested.

Following the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High, the state had empaneled a grand jury to review school safety, including what are commonly called SESIR reports that serve to “track incidents and analyze patterns of violent, criminal or disruptive activity” at schools.

In an interim report publicly released six months before Clayton’s arrest, the grand jury held up Duval as an example — under the heading “One Unfortunate Case In Point.”

Their conclusion: Duval had been intentionally misreporting incidents through a system of assigning Duval County School Police case numbers to complaints without any real investigation to follow up. (Records show that in July 2019, Duval had confessed to the state its own failure to correctly report more than 2,000 SESIR cases — something the district blamed on a “technical glitch.”)

The grand jury also found district administrators had directed Duval County School Police Chief Micheal Edwards — who had been appointed to lead the relatively new police force in 2015 — to train officers not to report “petty acts of misconduct” or misdemeanor crimes to other law enforcement agencies. And, the grand jury heard district police officers’ testimony that Edwards told them to discourage victims from putting suspects into the judicial system.

Edwards resigned in January 2021, following the release of an earlier interim grand jury report that detailed some of Duval’s SESIR issues.

The initial allegation that former Film Department Chair Corey Thayer inappropriately touched a student — which the victim later testified was sexual battery — was reported to police in 2015.

Documents show Duval County School Police soon closed its investigation, citing a request from the student’s father. Since 2015, the accuser’s family has maintained the father actually asked investigators to wait to interview his daughter until after she completed a course of psychological treatment.

The student’s mother remembers a telephone conversation between a school police detective and her husband.

“On that particular call…the officer was very obtuse — he was on speaker — and acted like he couldn’t care less,” she says. “Over the course of this entire saga, I have been spoken to many times in a manner that was discouraging us.”

A former district-level professional standards investigator, who spoke with Jacksonville Today on the condition of anonymity, remembers school police as hesitant to open sexual misconduct investigations.

“[DCSP] wouldn’t take anything,” the investigator says. “They wouldn’t take anything. They only wanted guns and drugs, and that was it.”

In August 2022 — following the release of the “unfortunate case in point” report that shined a public spotlight on Duval — state Office of Safe Schools Director Tim Hay wrote to then-Superintendent Diana Greene, telling her the SESIR reporting issues required “immediate action” and that his office expected her “full cooperation.”

Documents show Duval Schools officials had already met with Hay’s office, though — at the district’s request — to conduct a “joint review of processes” and had been working to correct issues since at least May of 2019.

A district spokesperson said in August of 2022, “Because of this collaboration with the state, we are confident that our current procedures are legally sound.” That October, the school board also authorized $50,000 to retain an outside law firm to review its reporting practices.

Questions mount

The SESIR reporting issues reared their head again after Clayton’s 2023 arrest, when state officials said they could not locate the SESIR report of the district’s 2021 investigation of his rubbing a student’s back during rehearsal.

And the incident reporting scandals didn’t end there. Less than a month after Clayton was put in handcuffs in front of Douglas Anderson, then-Duval Schools Office of Professional Standards Supervisor Reggie Johnson sent the state a cache of previously unreported teacher misconduct cases that should already have been forwarded to the Education Department’s Office of Professional Practices, going back several years.

Greene would deal with the fallout of that mailing and the lingering SESIR reporting controversy at the same time she was also fielding concerns from School Board members.

Here’s a timeline:

- Week of April 10, 2023: Several School Board members asked Greene to provide documentation that showed the district correctly reported Clayton’s 2021 incident to the state, as well as information about the “number of complaints against teachers who reportedly had inappropriate contact or communication with students.”

- Week of April 17, 2023: Every day this week, district records show, Johnson, the Office of Professional Standards supervisor, swiped his badge to enter district offices around 4 a.m. — much earlier than usual. According to a resulting state Office of Inspector General report, during this week, Johnson deleted about 200 files from his computer. At the end of the week, the state received the 50 “delinquent cases” he’d mailed to Tallahassee.

- April 19, 2023: Greene received a digital letter from Scott Strauss, an administrator in the state Education Department’s Office of Safe Schools, asking her if the district reported Clayton’s 2021 investigation as a sexual harassment SESIR incident. In her response sent April 21, Greene told Strauss that the district’s findings did not warrant that kind of report, but provided documentation to show the district had reported the incident in two other ways: to Professional Practice Services and to the Department of Children and Families.

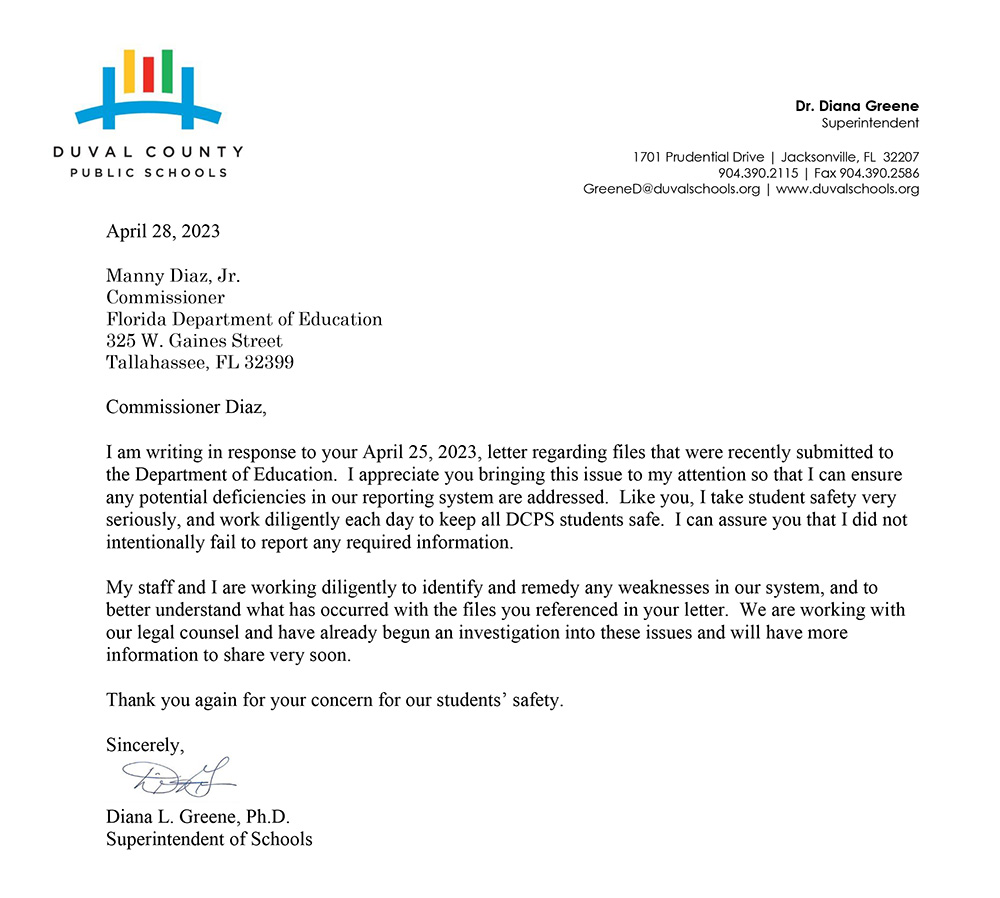

- Tuesday, April 25, 2023: Greene received a letter from then-Education Commissioner Manny Diaz threatening to slash her salary — a response to receiving the delinquent cases. She also responded to School Board member Charlotte Joyce (the current chair of the seven-member board) and provided several documents of teacher misconduct data created from the investigation spreadsheet, similar to what she’d sent Strauss the previous day. Some of these records were what Jacksonville Today used to analyze the districtwide data.

- Greene responded to Diaz on April 28: “I can assure you that I did not intentionally fail to report any required information,” she wrote.

In an email response to Jacksonville Today for this story, Greene said Johnson alone compiled the spreadsheet she distributed post-Clayton, and only later did she learn the state did not receive certain files.

“The internal processes in place at the time were built on the assumption of accurate reporting by the Office of Professional Standards. Once it became clear that this trust had been violated, corrective action was taken immediately,” she wrote.

- Wednesday, April 26, 2023: Johnson was reassigned to temporary duty and then resigned. He did not respond to requests for an interview for this story.

Since the Douglas Anderson scandal, the Duval School Board has approved policy changes to address incident reporting “weaknesses” and prevent future sexual misconduct. A district spokesperson says Superintendent Christopher Bernier — who came to Jacksonville about a year ago — has implemented “significant changes,” many of them first shared in a 20-point plan crafted by interim Superintendent Dana Kriznar. Duval Schools employees are now required to contact students only through the district’s official tools, and they must limit physical contact to high-fives, fist bumps and handshakes, for example.

What causes teachers to misbehave?

“I love Douglas Anderson, and it broke me,” says a theater grad who’s in the process of filing a lawsuit accusing former Douglas Anderson teacher Michael Higgins of “emotional, sexual and physical abuse.”

“There’s a lot of apologetics that goes on with the survivors and the victims,” he says, “but again, it’s very complex because we love these abusers.”

Charol Shakeshaft, a Virginia Commonwealth University professor who researches sexual misconduct by educators, says abuse in schools often happens not because an educator sets out to abuse but because small boundaries get crossed — sometimes unintentionally — and no one says anything.

“And then they cross another boundary, and then they cross another boundary, and pretty soon they are attracted to this student and they thought, ‘Well, nobody said anything — I guess I’ll just go ahead,’” Shakeshaft says.

She says one of the strongest predictors of misconduct is organizational culture.

“It’s a culture of not voicing concerns, a culture of not bringing up uncomfortable questions, a culture of not educating and preparing and training your faculty — not just about what is appropriate and not appropriate, but about what kind of things, if you see them happen, you need to report them,” Shakeshaft says.

She says she’s studied non-traditional schools, including arts programs, and “being an arts school” isn’t in itself a predictor of employee sexual misconduct. But schools with a creative culture can sometimes foster greater “faculty autonomy” — when teachers have “loose boundaries and a lot of freedom and not a lot of oversight” — and that can lead to issues.

And at schools like Douglas Anderson, where students perceive their future success in cutthroat industries depends on teachers’ support, students may have an incentive to keep quiet when boundaries are crossed.

Another theater department grad, who asked to remain anonymous because of his current employment, recalls students viewing Higgins as “a godlike figure.”

“We all wanted to be in his shows. So whatever he did, we didn’t question that because we wanted to be in his good graces,” he says.

Douglas Anderson alum Katie Sacks says friends she met after high school had similar experiences at other arts schools.

“There’s not a single person I know who went to a performing arts high school that didn’t have at least one problem teacher, or problems within the administration at the school,” she says.

Jacksonville Today sent requests for records about employee misconduct to six major arts high schools around the country — in cities like New York, Chicago and Los Angeles — many of which are members of the Arts Schools Network like Douglas Anderson.

All but one school did not respond. The Baltimore School for the Arts, which served as the model Duval Schools officials studied as they were creating Douglas Anderson back in the mid-80s, shared a district investigation report from when it went through its own reckoning over alleged teacher sexual misconduct and bullying during the 2020-21 school year. Baltimore, like Duval, has implemented policy changes as a result.

‘Why I fight so hard’

Early Douglas Anderson Principal Jane Condon wrote in her memoir that she purposefully hired artists at the top of their fields instead of certified teachers to teach many arts classes — something that required getting the district’s HR policy changed.

Dozens of former students and teachers tell Jacksonville Today that D.A.’s arts teachers were seen as connections who opened doors in ruthlessly competitive creative industries.

“You got to think these arts directors had contacts at Julliard, had contacts on Broadway, in Nashville, in Hollywood — these names carried weight at some point,” says Shyla Jenkins, whose mother’s tenure on the Jacksonville City Council began right after her freshman year at D.A., and who has recently become one of the community’s most vocal advocates for students.

“And that’s really, at the heart of that school, is what it is — that opportunity for geeky, nerdy arts kids like myself, to meet grown geeky, nerdy arts kids, and really have that camaraderie,” she says.

Jenkins, a gifted vocalist who has built a career in the financial services industry, remembers being mesmerized as a 5-year-old by Judy Garland’s singing in The Wizard of Oz. She also remembers feeling “expendable” as an arts student, knowing there was a long line of kids behind her who would be glad to take her spot if she struggled — or questioned the status quo.

“No, it’s not just because it’s an art school, but it’s the fact that the arts community is so small in Jacksonville and across the nation…coming forward ostracizes you not just at D.A., but also throughout. And that’s where it’s so different than any other high school,” she says.

Still, she hopes the tremendous opportunities D.A. offers are not eclipsed by the recent scandal. “It’s what I think got stolen from a lot of us,” she says.

So while she’s become a familiar voice calling for change at Douglas Anderson, she hopes the essence of the school will not change.

“In the advocacy I’ve done, what I’ve tried to reinstate at the school in building that culture back is like, ‘This is what the school is. This is what the school could be,’” Jenkins says. “And that’s why I fight so hard for it.”

This story is the third in a series, The Show Must Go On, examining the handling of reports of teacher misconduct at Douglas Anderson School of the Arts — and what’s changed in the more than two years since Jeffrey Clayton’s arrest. The final story is about the changes the district and school have made to make sure it won’t happen again.