This June marked one year since the sentencing of Jeffrey Clayton, the former Douglas Anderson School of the Arts Vocal Music Department director who’s serving a decade in prison for inappropriately touching and kissing a student.

This story is the second in a series, The Show Must Go On, based on tens of thousands of pages of public records and historical documents, as well as dozens of interviews with current and former Douglas Anderson students, parents, teachers and administrators.

In the early 2000s, Dani Burgess was floundering under the weight of bullying at her high school. About to drop out and get a GED, Burgess says her mom convinced her to first audition for Douglas Anderson School of the Arts.

“I think my mother knew that it wasn’t just my education…at risk,” Burgess said. “I think she knew that my life was at risk.”

Today, Burgess is a professional photographer with ambitions of becoming an art teacher. Back then, she loved to make stop-motion animation movies. To audition for D.A., she used one of her favorites — a Godzilla-style story she created with some winter decorations her mom had made out of felt.

“And I got in…I don’t think I would have completed high school had I not gotten in,” Burgess says. “At D.A., I wasn’t the weird kid.”

Burgess blossomed in a class called stagecraft, where students make the high-end theatrical sets the school uses for its elaborate productions. She particularly enjoyed metalwork, a process that includes grinding metal.

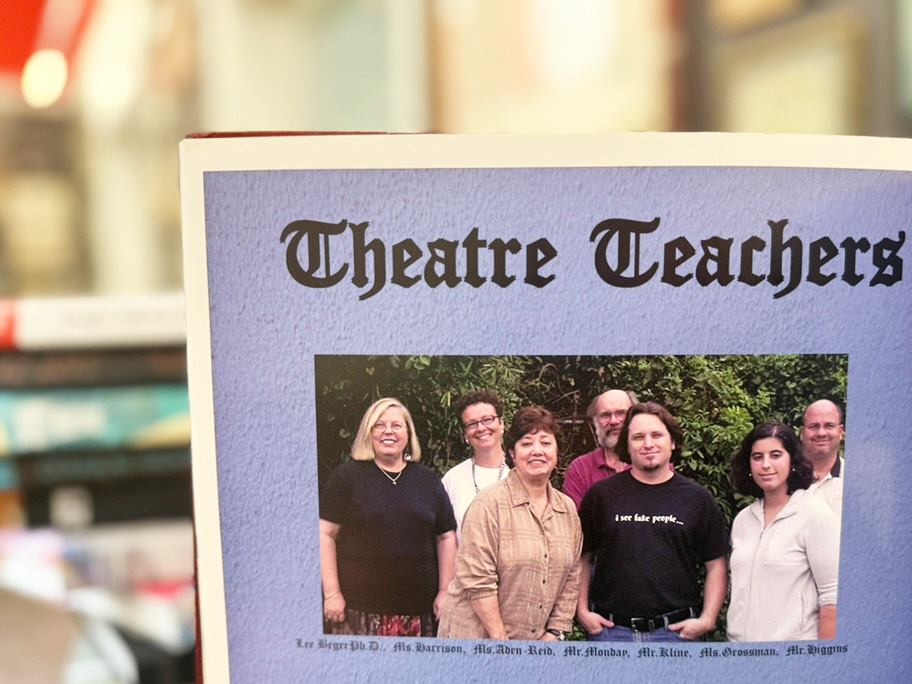

She says the teacher, Tim Kline, nicknamed her “Grinder Girl.”

Kline seemed to pay more attention to her than to other girls in the class, Burgess says. Soon, he began to push for her to come in on Saturdays for private lessons.

“After turning that down a bunch of times, it got a little less covert,” Burgess says. “It turned into him making this smug, slimy expression and saying, you know, ‘You can come grind with me anytime’ and a lot of comments like that.”

Kline did not respond to Jacksonville Today’s requests for an interview.

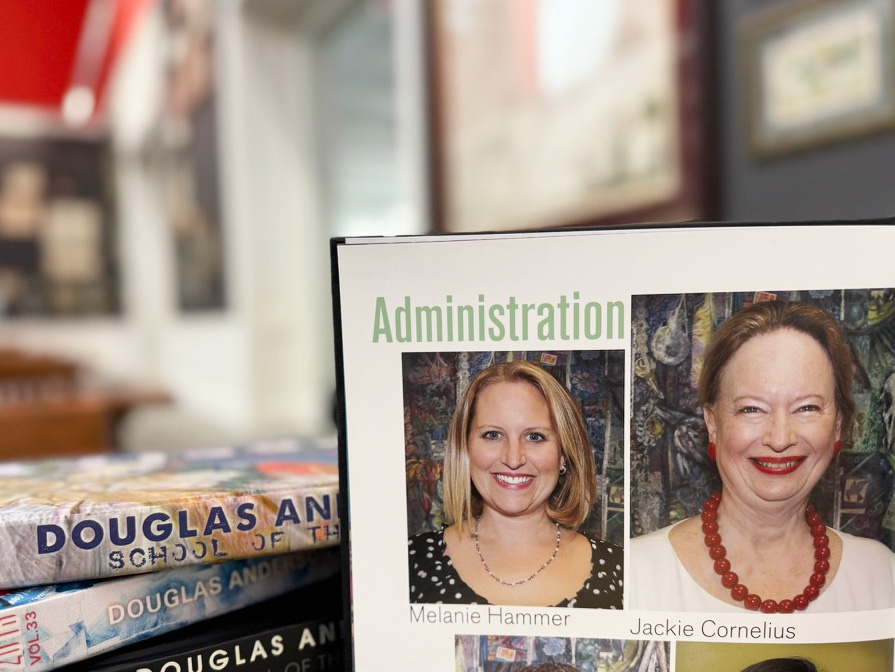

Burgess says she reported Kline to then-Principal Jackie Cornelius. She left the meeting feeling that Cornelius was not interested in addressing the teacher’s behavior.

“I kept pressing because it made me uncomfortable, and I knew teachers should not be talking to students that way — no adults should talk to children that way,” Burgess says. She recalls the principal ended the conversation with something to the effect of, “Well, you’re a young woman, and as you grow, you’ll learn to just expect to be uncomfortable.”

“And that…that really set a tone for a long time in my teens and 20s — that I should just expect for that to be what it was like for women,” Burgess says.

Cornelius, who retired from Duval Schools in 2017, declined an interview with Jacksonville Today and did not respond to a list of questions, including about Burgess’ recollection.

There is no record of a school investigation in Kline’s personnel file. He left Douglas Anderson in 2005.

Three years later, he was arrested in Walton County, Florida, and charged with sexual battery against a 12-year-old girl. Court records show he was found guilty of lesser charges of lewd or lascivious conduct and sentenced to six years in prison and restitution of $22,000 to the victim’s parents. His sentence was then suspended, and he served 10 years of probation instead. He remains a registered sex offender.

Jeffrey Clayton is the most infamous Douglas Anderson teacher, but his story is not unique. His 2023 arrest seemed to set off a reckoning: Six more teachers accused of sexual misconduct have since left the classrooms of Jacksonville’s nationally acclaimed arts school in quick succession — adding to the at least six D.A. teachers in the decades prior who had been accused of sexual misconduct against students and were removed or exited.

District spokesperson Laureen Ricks tells Jacksonville Today, in the last year, Duval Schools has changed a number of policies to “address system weaknesses, prevent employee sexual misconduct, and protect students.” Teachers accused of certain kinds of misconduct must immediately be removed from student contact, for example, and employees who don’t report misconduct allegations are themselves subject to discipline as well.

The Florida Department of Education requires schools to report sexual misconduct to the state, including sexual assault, sexual battery, sexual harassment and other sexual offenses.

Before Clayton’s arrest, many Douglas Anderson students lacked faith that school administrators would take such complaints against arts faculty members seriously. Jacksonville Today spoke with or reviewed letters from more than 20 former students, parents and faculty members who said they or a trusted adult had reported an arts faculty member for sexual misconduct, but they say their complaints either did not result in punishment or seemed to be minimized or ignored. Some of their reports appear in the district’s official records, and others do not.

‘Nothing further needs to be done’

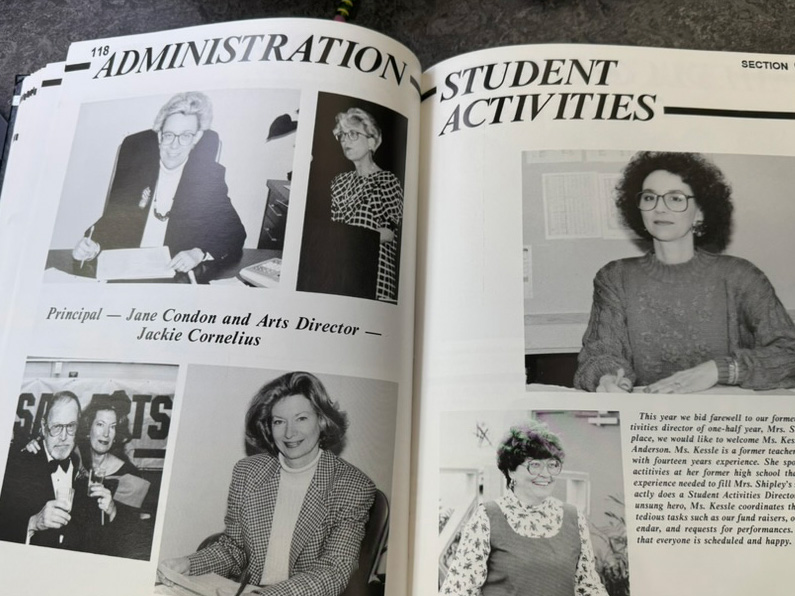

Early Douglas Anderson Principal Jane Condon died in February at age 86. In her 2021 self-published memoir, Chosen By Jane, she described a situation at D.A. that she said could have cost her and a teacher their jobs: The teacher, who was supposed to be supervising a weekend rehearsal, didn’t notice that five high school seniors had stripped naked and videotaped themselves. The racy recording came to light later, when a different teacher played the VHS tape for an art class, expecting it to be a lesson on Impressionism.

And so, along with a district employee, Condon strategized how to keep the episode off the books because the supervising teacher was one of the school’s most “creative and effective,” and Condon didn’t think it fair for either of them to be punished for the “mistake” of not noticing the nude videoshoot.

“I called a friend in Human Resources to ask what to do. He said, ‘You understand that you are NOT telling me this. I am NOT hearing this. And do NOT tell me who the teacher is. Otherwise, I would have to take action.’

‘Got it,’ I agreed.

He continued. ‘You have some choices. If you write up the incident report and give it to the teacher, you must also turn it in to me, and I would have to act on it.’

I said, ‘How about this: I write up the incident report, show it to the teacher, and file it away. If no parents come to complain by the end of the year, I will give it to the teacher, and nothing further needs to be done.’

‘That could work,’ he said. ‘Be sure you make only one copy of the report and keep the report yourself. If anyone gets hold of it, you’ll have to make it official.’

Thankfully, no children reported it, no parent complained, and I turned it over to the teacher the last day of school. Situation contained.”

When Condon exited D.A. in 1996, she selected the school’s then-arts director, Jackie Cornelius, as her successor.

“I knew Jackie had the knowledge, the skills, and the experience to run the school the way we had together,” wrote Condon.

Larry Zenke, who was Duval superintendent at the time, tells Jacksonville Today that although he does not remember the specifics of choosing Cornelius, “Jane’s support would have been very important.”

Cornelius would serve as principal for the next 20 years.

‘I can’t do everything’

One accuser’s “whole life” had been making films before she arrived at D.A., her mom tells Jacksonville Today. As a kid, she used a flip phone to make videos, and she had a corner of her bedroom devoted to staging her movies. Her mom says her teachers knew early on that she was brilliantly creative.

She was a freshman at Douglas Anderson — 14 years old — when she told her mother she was anxious about the sound booth in the school’s Film Department.

“You have to tell the principal that they have to lock that door,” her mom remembers her daughter saying. “There’s really bad things that happen in there.”

The mom says she went to Cornelius and told her that, along with other reasons her daughter was feeling unsafe on campus.

“‘I can’t do everything, Mrs. [name].’ That’s exactly what she said to me. ‘I can’t do everything, Mrs. [name],’ and it was just horrifying,” she recalls.

Cornelius did not respond to a question about the mother’s recollection.

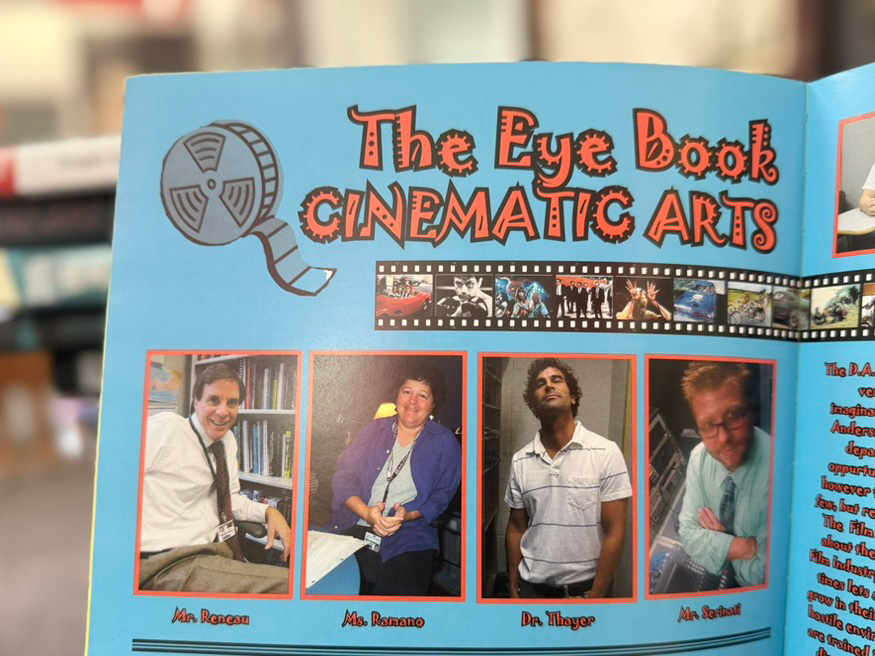

In the spring of 2015, the student’s mother filed a police report accusing Film Department Chair Corey Thayer of a “sex crime.” According to the police report, the student told a mental health counselor Thayer, then 43, had “touched her breasts and vagina over her clothing in a lewd manner.” School police soon closed the case, saying the student’s father had asked to do so — a claim the family has disputed in sworn statements to district investigators and in interviews with the State Attorney’s Office and Jacksonville Today.

Then-Duval Schools Professional Standards investigator Aaron Clements received Thayer’s case file in September 2015, but he did not investigate “due to other cases rising to a higher importance,” district records show. Jacksonville Today requested a list of cases Clements worked on that fall, but the district said it could not produce that record.

Almost a decade later, the district again investigated Thayer. The email records of several Duval Schools administrators, provided through public records requests, show the district received multiple complaints about Thayer in the month following Clayton’s 2023 arrest.

One such report came from the former student’s mother, who contacted the School Board on April 25, 2023. Then-Principal Tina Wilson sent a message to Douglas Anderson families that same day, announcing Thayer had been moved “to duties off campus and without student contact” and would be the subject of a district investigation.

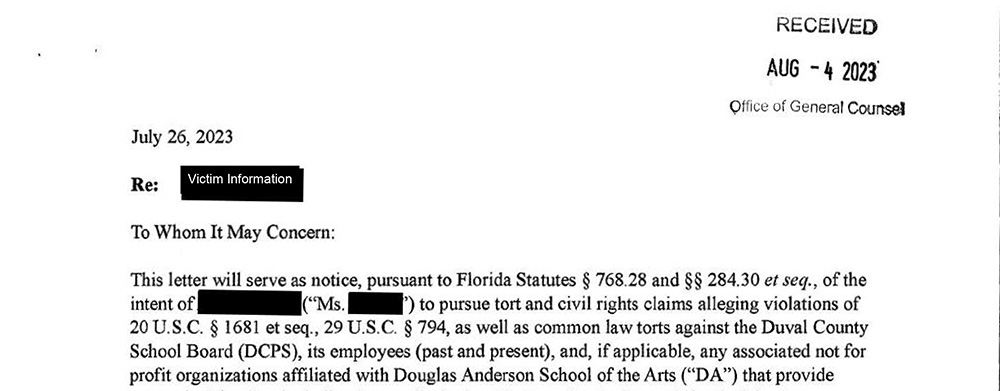

Records show district investigators did not speak with Thayer’s accuser, her lawyer or her parents during the course of that investigation, however. That’s despite district officials being made aware of the alleged “sexual intercourse” in a pre-suit notice received by the district from the accuser’s lawyer on August 4, 2023.

The resulting investigation report said allegations against Thayer could not be substantiated for “current” students (underline theirs), and Thayer was soon returned to the classroom, on Aug. 7.

A few weeks later, records show several people — including the student’s mother, her lawyer and community advocate Shyla Jenkins — questioned the district about Thayer’s return to teaching. He was again placed on administrative duty outside the classroom, where he remained until his resignation at the end of the school year. Then-Superintendent Dana Kriznar cited “new information” the district had received about Thayer’s conduct.

Professional standards investigators this time directly interviewed the original accuser. In a sworn interview, the former student accused Thayer of coercing her into sex multiple times. In the sound booth.

“I didn’t tell anybody the extent of what was going on,” she told the investigator in 2023. “I told…my friends in freshman year about how I was ‘Thayer’s favorite’ and stuff, but I never told them the extent of what happened because I didn’t — I knew that it was wrong, so I didn’t want to really share that.”

The district settled the civil complaint with Thayer’s accuser last year without an admission of liability.

After an investigation that spanned two school districts, the State Attorney’s Office last month decided not to file charges against Thayer.

“While the victim has given a very credible recounting of her abuse at the hands of Thayer, the passage of time creates significant impediments to proceeding on this case. There are no witnesses, no physical evidence, and no other corroborative evidence,” wrote Assistant State Attorney Anna Hixon, who also prosecuted Clayton.

The SAO noted the victim’s priority was that “Thayer not be able to return to the classroom.” After Jacksonville Today first reported what led to Thayer’s resignation, the state of Florida revoked his teaching license on July 9, 2025.

Thayer did not reply to Jacksonville Today’s invitations to respond to the allegations.

Opening the floodgates

Jade Collins was a theater major who graduated in 2019, the year before COVID shut the world down. She says she had a “mostly positive experience” at Douglas Anderson. But after graduation, she realized through talking with friends at college how “strange” some of the school’s culture was.

As the the viral #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter movements converged online in the pandemic summer of 2020, Collins used social media to collect stories of racial tension at Douglas Anderson. Stories of sexual misconduct soon flowed too. Collins eventually met with then-Principal Melanie Hammer over Zoom to debrief her on what she’d heard.

“I remember feeling like the D.A. alumni community was really coming together,” Collins says.

Hammer did not respond to interview requests for this story.

Shyla Jenkins, an alum and community advocate for change at the school, says, “Jade really paved the way for all of us to come forward and say, ‘This is something that has to be addressed.’ Before that, D.A. was untouchable. D.A. was the perfect school that pushed out these great, amazing kids — but many of us knew the cost of that.”

‘Higgins Boys’

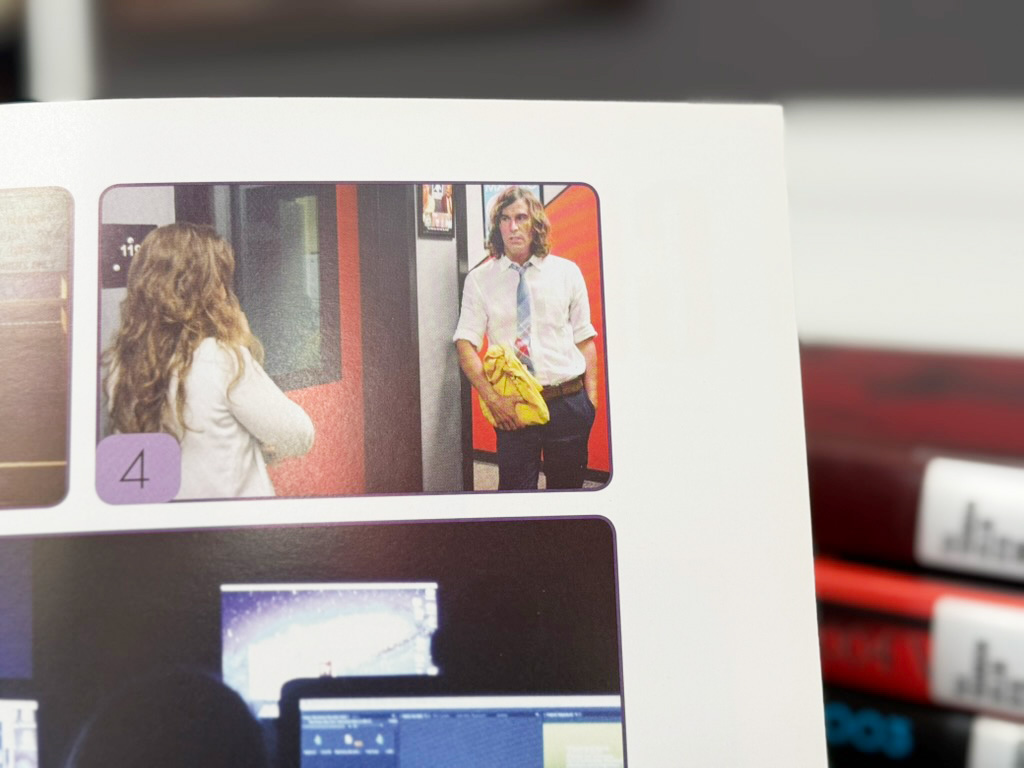

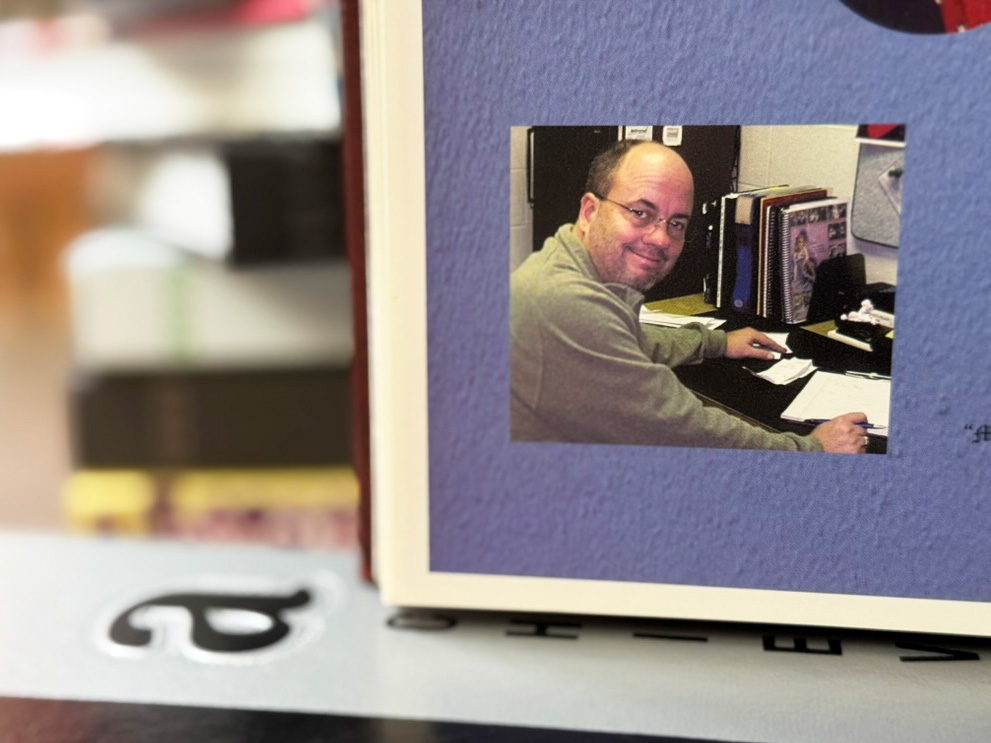

A theater teacher who’d taught at Douglas Anderson since 1993, Michael Higgins, came up again and again in the stories shared online that summer.

Higgins was investigated for alleged “sexual abuse,” according to district records, shortly before he left the school in July of 2020. The district currently faces the prospect of a lawsuit from one of his accusers, who alleges in a pre-suit notice “emotional, sexual and physical abuse, sex discrimination and sexual harassment”— and also alleges, after he was “consistently groomed and abused” by Higgins for three years, that a guest lecturer at Douglas Anderson also sexually battered him.

“So many people I’ve met in media, in theater, in film, had these lovely experiences with mentors. They have someone that brought them up and facilitated who they are and saw their gift and nurtured it. My mentors took away my gift,” the accusing student tells Jacksonville Today. “The way that I have found to be creative in the arts is fulfilling, but it’s one of those I look back and I go, ‘Damn, what if — what if that had been just a little different? And what if the safety nets that are there had caught me?’ Then I wouldn’t be broken.”

A district spokesperson did not specifically address the allegations against Higgins in response to Jacksonville Today’s questions but did refer to recent policy changes meant to “prevent employee sexual misconduct.”

In an email to then-Superintendent Diana Greene, another former student alleged that, in preparation for a role, Higgins had isolated her for hours and had another student beat her until she was black and blue.

“I was so desperate to get a full scholarship to college that I would have done anything to please that teacher,” the student wrote.

Higgins’ reputation at Douglas Anderson was equal parts brilliant and difficult, according to interviews with seven of his former students.

“Michael Higgins is a genius. What he knows about theater, how he analyzes theater and how he directs — truly is at a superior level,” one of them says. “I think the reason he stayed in high school theater was because he wanted to be so powerful and have this sense of power over the students.”

In a text message response to Jacksonville Today, Higgins said he was “offended” at the suggestion that he was “involved in any wrong-doing while serving as a teacher at Douglas Anderson School of the Arts.”

He did not respond to invitations to address the specific allegations against him.

“My experience was very positive at D.A.,” Higgins wrote. “I have been happily retired for five years and know nothing about the administration of Duval County Schools. All of the leadership has changed from my days of employment.”

D.A. alum Veronica Vale remembers a familiar scene in the mid 2010s: Down a labyrinth of brick halls behind Douglas Anderson’s impressive theater was a heavy metal door. Higgins’ office.

Vale would be coming back from making copies for Higgins. His door would be slightly cracked, the sound of laughter spilling out. Lunch with a boy. “Higgins Boys,” the students called them.

“It was always the same. It was never some random. It was like he had a target — or his favorites,” Vale says. “The joke that we had growing up was, ‘Oh, you’re a ‘Higgins Boy.’”

Earning and keeping a spot among the Higgins Boys wasn’t easy, the seven former students say. One wrong move — like a bad performance or an ill-timed opinion — would get you ousted.

“I would have done anything to be a Higgins favorite,” says one alum who fell out of the teacher’s favor. “I would have been…I would have done anything that that man asked me to do to be back in his good graces.”

All of Higgins’ former students who spoke with Jacksonville Today recall his instructing teenage boys to kiss, wrestle or wash each other while he looked on — what one self-described former Higgins Boy now calls a misuse of the Growtowski Technique, a legitimate theatrical teaching method that focuses on actors’ physicality.

“It’s five of us, in a room alone with him, getting private tutelage from this brilliant man,” recalls the alum. “And so when the older boys start taking off their shirts to get more comfortable, you take off your shirt to get more comfortable. And when the older boys take off their pants — to really loosen up because the clothing is somehow affecting our ability to grab one another — then you take your pants off, too. And all of a sudden you’re wrestling in the theater lobby in the middle of school hours for Mr. Higgins.”

Higgins retired on July 31, 2020, and collects a more than $3,000 monthly pension, according to state records.

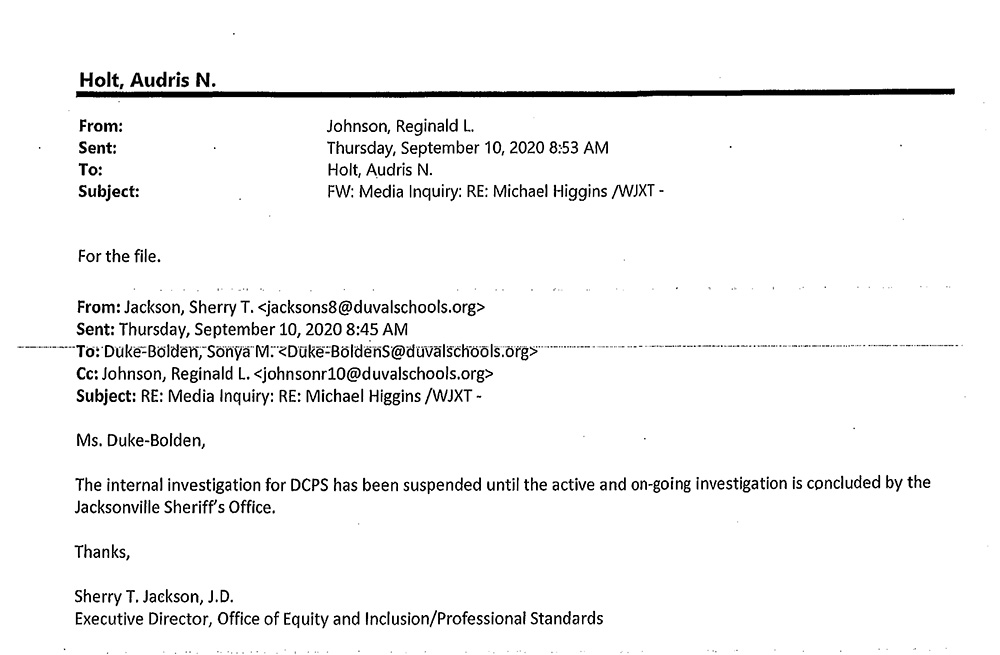

A Duval County School Police report shows the agency briefly investigated Higgins that summer and then forwarded the complaint to the “appropriate jurisdiction” for follow-up. District emails suggest the receiving agency was the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office, but JSO tells Jacksonville Today it has no record of investigating Higgins.

Records in Higgins’ personnel file indicate the Florida Department of Education in 2022 declined to investigate him after Duval Schools forwarded the 2020 misconduct complaint. The state wrote that the information provided “was insufficient in that it [did] not support a violation of pertinent statute or rule over which [the state] has authority to pursue investigation.” His teaching license remained active until June 30, 2025, when it expired.

Another D.A. teacher, Craig Leavitt, was removed from teaching last year while he was investigated for an alleged “inappropriate communication” with a student during the 2021-22 school year.

The accusing alum tells Jacksonville Today Leavitt, a special education teacher, took an interest in him after coming to his math class to help other students.

“There was no reason for him to be talking to me,” says the former student, who has retained counsel to bring a lawsuit against the district.

Leavitt did not respond to Jacksonville Today’s invitations to comment on the allegations against him.

A pre-suit notice the district received last September alleges Leavitt “lavished [the student] with praise, made romantic and sexually charged comments fixated on [the student’s] physical appearance” and told the student that he had once been “investigated and exonerated for grooming behavior.”

The student says Leavitt began messaging him during the 2021 school year through social media. Monologues that became too personal. He promised help with college applications (though he didn’t deliver) and offered financial help while at the same time complaining that he was struggling financially, his pre-suit notice says.

A few months after the boy had graduated, Leavitt began messaging him in the middle of the night through the app Grindr, screenshots reviewed by Jacksonville Today show.

“When I was in school, it wasn’t obvious, but reading that now? It’s just like, oh my God, I can’t believe he sent that to me,” the former student says. “Yeah, it’s like…it makes you want to take a shower.”

Leavitt’s personnel file also includes a record of a previous investigation in September 2019. According to a statement from a teacher, another student told him Leavitt “creeps me out” because of messages he sent in the middle of the night. That allegation was determined unsubstantiated after the student gave a written statement saying “nothing inappropriate has occurred.”

‘A list of names’

During the summer of 2020, another Douglas Anderson alum emailed then-Principal Melanie Hammer: “This is a list of names you should know, and if any still teach at the school in 2020, cover your ass and fire them… cause you aren’t the first person to get this list. And they all f*** children.”

A dozen names followed.

As of the summer of 2025, all of them have left the school, with at least seven resigning or being terminated amid sexual misconduct investigations before or after the “list” email was sent. One was arrested in Canada in 2022 on charges of sexual assault and is awaiting trial. The last one remaining, a part-time Douglas Anderson staffer, was removed on April 22, 2025, during an investigation of unspecified alleged “inappropriate conduct.”

The email’s author told Hammer that he had already talked with professional standards investigator Reggie Johnson.

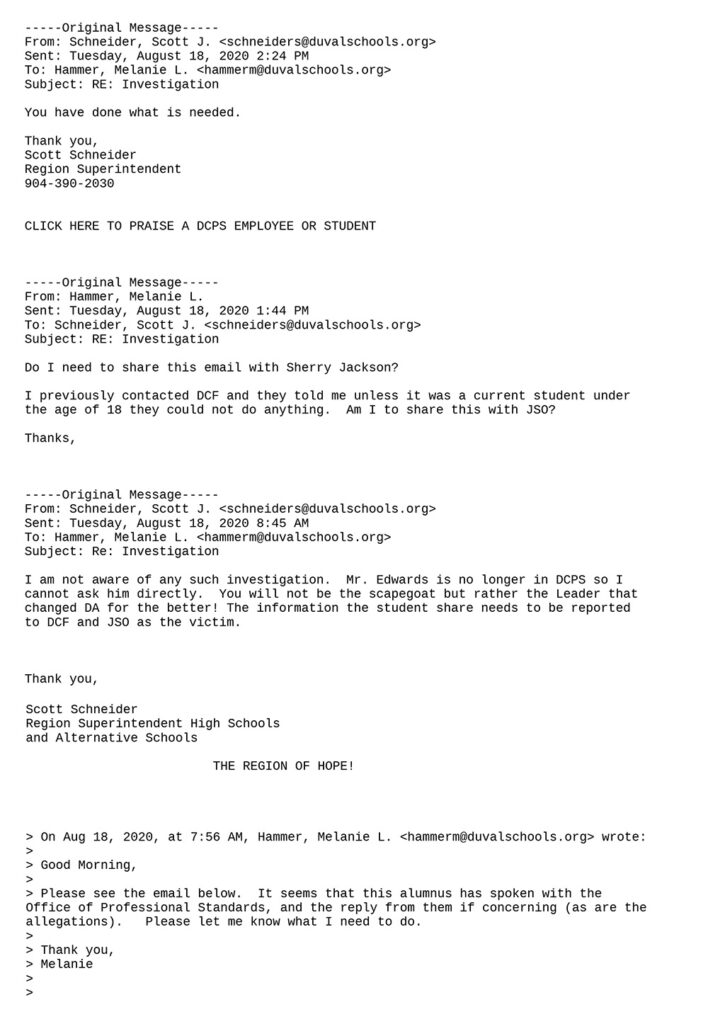

Emails provided by Duval Schools show Hammer forwarded the 2020 “list of names” email to then-Region Superintendent Scott Schneider, her supervisor, and asked whether she should report it to the state, the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office or another high-level administrator. Schneider told her she had “done what is needed.”

Jacksonville Today asked the district whether Schneider forwarded Hammer’s email or the list of names to anyone. No records were found to show he had.

Schneider, who was recently a finalist for St. Johns County County School District superintendent, is still employed at Duval Schools HQ. He declined an interview with Jacksonville Today and responded by text message, “This is still a matter of litigation so it would be inappropriate for me to address any questions at this time.”

‘The signs were there’

In 2024, the district settled a civil case with another former student who accused Film Department teacher Nicholas Serenati of sexual advances, including explicit texts. The district did not admit to any wrongdoing.

The accuser says, about 15 years ago, the department’s three faculty members, including Thayer, shared a small office. She says she spent most of her lunch periods with Serenati and even skipped classes to be with him. They spent “a pretty ridiculous amount of time together.”

Serenati did not respond to Jacksonville Today’s invitations to comment for this story. He left Douglas Anderson in 2016 and joined the faculty of Flagler College, where he stayed until last year. State business records show he now owns a youth soccer club in St. Augustine.

The former student, now an adult, says his texts came at all hours of the day and into the night. Her pre-suit notice alleged Serenati sent “hundreds of inappropriate text messages…of an explicit and deviant nature,” talking graphically about her body and asking for nude photos.

“Each day and over a period spanning months, during school hours, both in his office and in the sound booth, Mr. Serenati made sexual advances toward her including sending her sexually inappropriate messages,” says the pre-suit notice sent to the district.

She tells Jacksonville Today she wishes other adults at Douglas Anderson had noticed she was struggling, as her grades were dropping and she was “isolating” herself.

She remembers Serenati telling her that his two officemates warned him that he may be spending too much time with the girl. She says he laughed it off, telling her they were just jealous.

“The special attention was very obvious. Obviously, other faculty members noticed it,” she says. “I think that’s what’s frustrating to me now as an adult — is that the signs were there.”

This story is the second in a series, The Show Must Go On, examining the handling of reports of teacher misconduct at Douglas Anderson School of the Arts — and what’s changed in the more than two years since Jeffrey Clayton’s arrest. The next story is about how D.A. compares to other schools — and how issues with the district’s data make accurate comparison difficult.