It’s been 10 years since a white supremacist entered one of the bastions of the African Methodist Episcopal church and murdered nine people during their benediction.

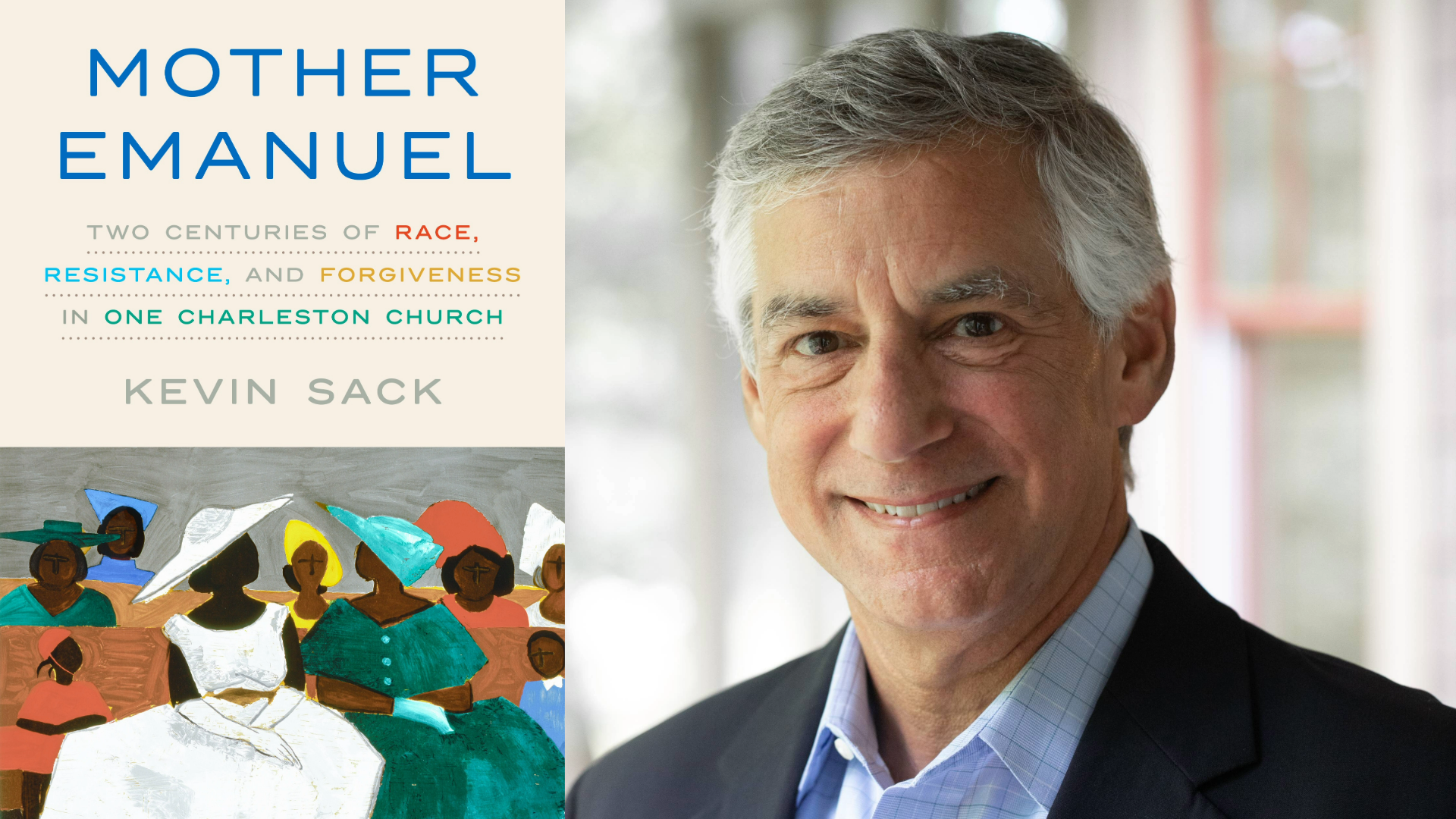

Jacksonville native Kevin Sack was in Charleston, South Carolina, in the aftermath of the shooting at Emanuel AME Church. Earlier this month, the Jacksonville native published his first book, Mother Emanuel: Two Centuries of Race, Resistance and Forgiveness in One Charleston Church.

On Friday, the Jacksonville Public Library will host Sack for a LitChat on Friday afternoon at its Main Library location Downtown on Laura Street at 4 p.m.

The one-hour conversation is free. However, people must have a Jacksonville Public Library card and register in order to attend.

It will be a homecoming for the former editor of the Bolles Bugle and Pulitzer Prize winner.

In 2003, Sack and Alan Miller combined to examine a military aircraft that was linked to the death of dozens of pilots for the Los Angeles Times.

In 2001, Sack was a part of a New York Times team that won journalism’s highest prize for its work exploring racial attitude and sentiment in the United States at the turn of the millennium.

Sack recently spoke with Jacksonville Today about his debut book.

Q: Why did you want to write this book at this hour of American history?

A: When the shootings happened in Charleston 10 years ago, I was just deeply affected, I think both as a native Southerner who had been a student of the Civil Rights Movement, and also as a journalist who had spent most of my career in the South and much of it — maybe an uncommon amount of it — in and around Black churches.

I covered the immediate aftermath for the New York Times and also came back to Charleston to cover the trial a little more than a year later. I very quickly got transfixed by the backstory of the place. So much had happened in the 200 years before that event.

What happened that night was going to become a major milestone in this country’s racial history. I felt a couple of things right off the bat. One, that it really mattered that the killer had chosen this particular target. People should understand why it mattered, and the church shouldn’t forever be known only for what happened that night because so much of import had happened before.

As I started to get more familiar with the history, I started to feel that the church provided this wonderful vehicle that would allow me to explore the history of African American Charleston over a two-century period, all within one metaphorical congregation under one roof.

Another thing that was driving this whole exploration is that … there was this amazing scene a couple days after the shooting in which a number of family members at a bond hearing for the killer stood up to a microphone and expressed forgiveness in one form or another toward this utterly remorseless 21-year-old white supremacist.

Like so many of us, I was both awestruck and befuddled by that all at once. As I dug into the history of the church, it began to occur to me that the answer to the question of how those people had stood up that day and done that might lie somewhere in the history of the congregation and of the denomination.

Q: How did your childhood in Jacksonville impact your journalism career and impact the reporting you did for this book?

A: You can argue that my journalism career started in Jacksonville. I was the editor of the Bolles Bugle. I’m very proud to say that was my first journalism job. It really did ignite my interest in the craft. …

Given that I wound up writing so much more about race over the course of my career — and, obviously, that’s the theme of this book — my life in Jacksonville was a very segregated one. I graduated in 1977. I did not have a single Black classmate the entire time I was in school in Jacksonville. …

I had very little sense of the city’s racial dynamics or of the place and history of racial strife in the South until I got to college. At which point, I was in a more integrated environment and had friends of all stripes and colors. I took history classes that led to my interest in civil rights history in particular.

I took a lot of modern American history courses that reflected on the Civil Rights Movement. I became enamored with the romance of that story. Then, my first journalism jobs were in Atlanta. I got there at exactly the moment where the city was transitioning from white governance to Black governance.

The people who were leading that transition, and who I wound up hanging around with many days, were folks like Andrew Young, John Lewis, Julian Bond, Joseph Lowry, Maynard Jackson and Hosea Williams. It was quite an early education. Black political power, and a lot of the city’s Black politics, took place in Black churches.

Q: The AME Church has this long history of promoting education, and Mother Emanuel was no different. How much do you think that considering where we are in terms of access to education and educational gaps … (describe) the way the Black church has been involved in pushing for educational advancement?

A: It’s certainly a critical role that’s been played by this denomination. Those who are familiar with the church’s place in Jacksonville obviously know about Edward Waters University, which is one of several AME colleges and universities and seminaries around the country.

There’s one here in South Carolina in Columbia, Allen University, which was attended by many of those who lost their lives on the night of June 17, 2015, including the pastor Clementa Pinckney and the youngest victim, Tywanza Sanders, who I believe was 26 years old and a recent graduate of Allen.

Yes, the denomination is closely linked to the HBCU community. And, I think there’s a lot of pride in both directions, both from the denomination and in those institutions.

It’s sort of interesting that early in the denomination — (during) antebellum and just after the close of the Civil War — there was almost an anti-intellectual streak within the denomination’s top hierarchy. Preachers were, I think, expected to be more spirit driven than to have a lot of book learning. And, that was a reflection of the times because until the Civil War, literacy wasn’t really obtainable for many African Americans.

After the war, (AME Church Bishop) Daniel Payne disdained this whole notion of an uneducated clergy and started to push for educational requirements for AME ministers.

There was some controversy over that for a while, but it was a fight that he eventually won. Now, its a highly educated and intellectual clergy.

Writer’s note: Emanuel AME Church was the first African Methodist Episcopal congregation in the South when it was founded in 1818 in Charleston.

This month is the 160th anniversary of the denomination’s presence in Florida. William G. Steward was sent from Charleston in April 1865. In June of that year, Steward founded Midway AME Church on Jacksonville’s Eastside. Mother Midway, as it’s affectionately called in AME circles and beyond, continues to open its doors from its location on Van Buren Street “in spirit and in truth”

Steward and the Rev. Charles H. Pearce were also instrumental in raising funds for a school. That school is now known as Edward Waters University, Florida’s oldest private educational institution. Edward Waters University has undergone a number of name changes since it was founded in 1866. Its current name is in honor of the third bishop of the AME Church.)

Q: You’re coming home on (Friday) to have a conversation about this book. What do you expect when you get to discuss your debut book in your hometown on Friday?

A: I think it’s going to be a moving experience. There will be friends and family in the audience. Jacksonville is not a fleeting part of my past. My entire childhood and youth were spent there, as was my wife’s. We’re both back there on a regular basis.

I think there are so many people who will be with us that day who have been with us across the entire 10-year path toward the production of this book. They have been loving, supportive and enthused. It felt really good to have that kind of hometown support. It should be a gratifying homecoming.