Champions of the manatee representing conservation, regulatory, educational and maritime commerce interests are collaborating to protect the sea cows in the St. Johns River.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that fewer than 8,400 Florida manatees exist. They are listed as a threatened species under the federal Endangered Species Act.

The Public Trust for Conservation is spearheading a committee of community stakeholders to save manatees while also supporting recreational and commercial uses of the river. They want the two to co-exist.

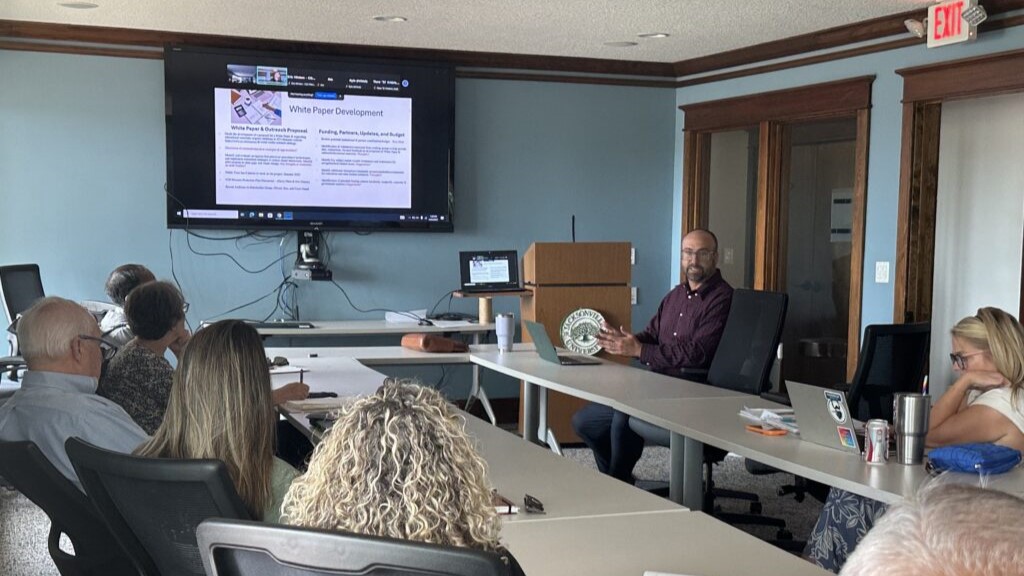

At a meeting Thursday at Jacksonville University, their discussion was especially geared to reducing manatee and watercraft collisions like the one in 2023 in the St. Johns River when a shipping vessel hit and killed five animals in a mating herd.

During 2024, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission recorded 565 manatee deaths in Florida, and about a fourth of those were caused by a watercraft strike.

“My job is to visualize where those things might conflict in time and space,” said JU Associate Professor Ashley Johnson, one of those on the committee who has expertise in technical geography and has mapped out parts of the river where the manatees hang out.

She also takes into account the animal’s seasonal migration because that affects what they’re doing. “If they’re feeding or if they’re just swimming along, they’re more apt to get out of the way, but if they are in a mating herd, they’re not paying attention,” she said.

When it comes to humans paying attention to herds of manatees, that is information that needs to get to the thousands of commercial ships that come in and out of the port of Jacksonville.

“It’s not stupidity; it’s not a lack of desire to do the right thing or a lack of concern for the animals. It’s just they just don’t know,” said Barrie Snyder, president of the St. Johns Bar Pilot Association, professional mariners who are referred to loosely as “stewards of the river.”

Snyder’s recommendation at the committee meeting was to increase information and awareness. He advocates simple, direct signage or placards of what to look for in every port.

“The ships coming in and out of here could be coming from literally anywhere in the world,” Snyder said. “And a lot of them don’t know what a manatee looks like, what the swirls will look like on the water, so what we’re going to be able to bring to them is education,” he said.

“The awareness that before we engage any equipment alongside the berth, such as bow thrusters, turning the propellers, and things like that is just a quick inspection alongside to make sure that we have no manatees there,” Snyder said. He advocates broadcasting the information and putting pilots and crew on the lookout for manatee groups.

Gerard Pinto, from JU’s Marine Science Research Institute, believes that manatees deaths from recreational boat strikes have decreased.

Speed zone signs along the river with a big orange circle tell people to go slower in buffer zones that extend 1,000 feet. Compliance has improved over the years. It doesn’t hurt that they used to have two marine officers in the area, and they now have eight.

Pinto says the group is also interested in habitat issues.

“Their habitat is suffering, and so there’s a separate focus to try to see what kind of management plans we can invoke that will help to revive the grass-fed habitat,” Pinto said. “Since 2017, habitat for manatees hasn’t been bouncing back after storms and now it’s been seven years and it’s having trouble.”

Theresa Hudson, a biologist with the environmental nonprofit law firm Public Trust, is on the committee and said members plan long-term restoration projects. They know that manatees go into the deepwater channel when they feel threatened. Hudson said.

“We’re hoping to give the manatee preferences,” she said. “We want to keep them in the shallow areas where they have food to eat and can rest. We want to provide habitat for feeding and resting, restore some shoreline that will benefit not only manatee but shoreline homeowners, and just make our community a nicer place for humans and manatee to co-exist.”

Public Trust for Conservation Executive Director John November said the group has just finished a white paper. With that document completed, they’ll secure more funding and start implementing the initiative.

“We’re entering the phase where we’re going to be utilizing new technologies and studying what best practices are available to implement here in Jacksonville, and the greatest part of all is that this could be an opportunity for other communities who are also interested in protecting manatees,” he said.