During the late 19th century, Jacksonville experienced a major industrial boom. Factories, mills and shipyards were established along the St. Johns River and near key railroad lines. By 1960, the city was home to more than 500 manufacturing and processing firms, earning Jacksonville the nickname “Industrial Capital of Florida.”

However, by the end of the 20th century, many of these original industrial sites had closed. In recent years, there has been a renewed interest in preserving and repurposing historic industrial spaces. A notable example is the Union Terminal Warehouse Co. warehouse on the Historic Eastside, which has been transformed into a mixed-use development.

At the same time, many significant industrial buildings have been lost. Here is a look at seven major industrial structures that were demolished, marking the end of an era in Jacksonville’s industrial history.

American Motors Export Company, 801 W. 15th St.

In 1921, American Motors opened in Jacksonville with the goal of manufacturing the Innes automobile. The car was the brainchild of Henry L. Innes and was intended as a revival of the short-lived Simms automobile, which had been produced in Atlanta, Georgia, only a year earlier in 1920. Innes had served as the production manager for the Simms Motor Car Co. before pursuing his own venture in Florida.

Henry L. Innes brought with him an impressive résumé in the automotive industry. Prior to arriving in Florida, he worked alongside the Dodge brothers on the development of the first Dodge vehicle, held a management position at William Durant’s General Motors and Chevrolet, and briefly served as vice president of the Doble-Detroit Steam Motors Co. Determined to launch his own luxury automobile brand, Innes chose Jacksonville as the home for his manufacturing operations.

True to its name, the Innes automobile was envisioned for the export market. It was an “assembled car,” meaning its parts were sourced from various suppliers and then put together at the Jacksonville plant. Tragically, Innes died suddenly at the age of 46, shortly after the completion of his Fairfax Street factory. At the time of his death, only six Innes automobiles had been produced. The plant was later repurposed by the Continental Can Co. to manufacture aluminum cans for the nearby Jacksonville Brewing Co., as well as by Howard Feed Mills.

From 1980 to 2010, the site was occupied by Wood Treaters, LLC, which specialized in pressure-treating utility poles, pilings, heavy timber and plywood products using the wood-preserving chemical chromated copper arsenate. The company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2009. Subsequently, low levels of arsenic contamination were discovered in nearby Moncrief Creek. The long-vacant former auto assembly plant was ultimately demolished in 2015.

Jacksonville Municipal Electric Light Plant, 4215 Talleyrand Ave.

In 1910, the Jacksonville Municipal Electric Light Plant was constructed near Talleyrand Avenue and East 30th Street along the banks of the St. Johns River. Originally known as the Talleyrand Generating Station, the facility was renamed in the 1960s in honor of J. Dillon Kennedy, a former City Council member who played a pivotal role in the growth of what is now JEA.

At the time, electricity in Jacksonville was supplied by the now-demolished Southside plant and a floating World War II-era power plant near NAS Jacksonville known as the Inductance. Both the Kennedy Generating Station and the adjacent National Container paper mill burned high-sulfur fuel oil, which periodically blanketed the city in black soot.The historic J. Dillon Kennedy Generating Station building was ultimately demolished in 2007.

Ford Motor Co., 1901 Hill St.

In 1923, Henry Ford purchased 10 acres of former shipyard property along the St. Johns River from the City of Jacksonville for $50,000, intending to establish a major automobile assembly plant. Constructed between 1924 and 1926, the arrival of the world’s largest automobile manufacturer marked a pivotal moment in Jacksonville’s rise as an economic hub. The total cost of construction and equipment reached approximately $2 million. To support the plant’s operations, the river channel was dredged, enabling Ford’s oceangoing freighters to dock directly at the site.

The original assembly plant encompassed 115,200 square feet of enclosed space. An adjacent powerhouse was equipped with a 500-horsepower boiler to generate steam for the plant’s electric turbo generators. The facility also featured its own fire protection system, supported by a water generation building that pumped river water into a 75,000-gallon storage tank. At the front of the building, a parts department and a showroom showcased finished automobiles to the public. In 1926, a 50,000-square-foot addition was built on the eastern side of the structure to accommodate growing production needs.

Designed by renowned industrial architect Albert Kahn, the Jacksonville Ford plant employed hundreds of workers during its peak. Although vehicle assembly ceased in 1932, the facility continued to serve as a parts warehouse until 1968. Despite its historical and architectural significance—recognized as one of the most important industrial buildings in Florida—the plant suffered decades of deterioration. It was ultimately demolished in 2023. The site is now home to the Jacksonville Machine and Repair shipyard.

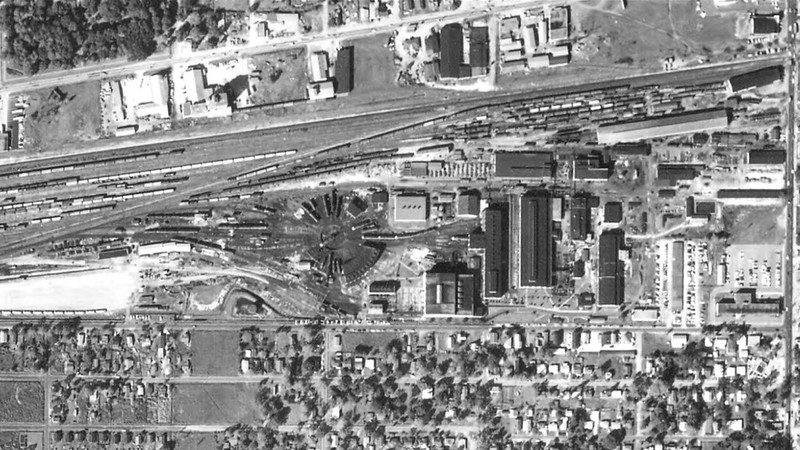

Atlantic and East Coast Terminal Co., 10 Jefferson St.

The Atlantic and East Coast Terminal Company was formed in 1910 by the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and Florida East Coast Railway. The freight terminal and supporting rail yard consumed eight continuous blocks between West Bay and Forsyth Sstreets, just west of Jefferson Street. At the time, the leading industries in Jacksonville were shipbuilding, lumber and cigar manufacturing. Partially destroyed by fire, the terminal, which included 1.48 miles of trackage, was demolished in 1979 following a relocation of its operations.

National Container Corp., 1915 Wigmore St.

Established in 1938 by Sam Kipnis, a Russian Jewish immigrant, the National Container Corp.’s paper mill replaced the former American Agricultural Co.’s Talleyrand phosphate works, which had been constructed along the St. Johns River in 1919. Under Kipnis’s leadership, National Container grew rapidly and became the third-largest box manufacturer in the U.S. by the time it was acquired by Owens-Illinois in 1956.

However, due to a court order mandating divestiture, Owens-Illinois sold the Talleyrand mill to the Alton Box Board Co. in 1965. In 1981, Jefferson Smurfit completed its acquisition of Alton Box, bringing the Jacksonville mill under its ownership. The subsequent 1998 merger between Jefferson Smurfit and Stone Container marked the beginning of the mill’s decline. As part of a company-wide reduction in capacity, 1.1 million tons were cut from operations—resulting in the indefinite shutdown of the Jacksonville containerboard mill, along with facilities in Circleville, Ohio; Alton, Illinois; and Port Wentworth, Georgia. Approximately 300 employees in Jacksonville were laid off.

For decades, the mill was known for producing a strong, unpleasant odor that permeated parts of the city. In 2005, the defunct facility was sold to Keystone Industries LLC and subsequently demolished.

Wilson and Toomer Fertilizer Co., 1611 Talleyrand Ave.

The Wilson and Toomer Fertilizer Co. was established in 1893 by Wylie G. Toomer and Lorenzo Wilson. Located on a 31-acre site along the St. Johns River and Deer Creek, the facility operated as a fertilizer formulation, packaging, and distribution center. In the 1950s, pesticide formulation operations were introduced, expanding the site’s industrial role.

At its height, Wilson and Toomer operated satellite factories across Florida in Tampa, Fort Pierce, Port Everglades, and Cottondale. The Jacksonville complex served as the company’s administrative headquarters and employed 500 workers.

Ownership of the plant changed hands several times beginning in the 1950s. Wilson and Toomer sold the facility to Plymouth Cordage, which later sold it to the Emhart Corp. in 1965. In 1970, the Kerr-McGee Chemical Corp. acquired the complex and operated two plants on-site. These facilities were used for the formulation, blending and packaging of pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers. Kerr-McGee also produced sulfuric acid on-site for use in fertilizer manufacturing and, for a time, ran a steel drum reconditioning facility adjacent to the pesticide storage warehouse.

Sulfuric acid production ceased in 1972, followed by the end of superphosphate fertilizer production in 1976. Fertilizer-blending operations were discontinued entirely in 1978. The site’s remaining buildings were demolished in 1989, marking the end of nearly a century of industrial activity.

Jacksonville Shipyards, Inc., 750 E. Bay St.

The origins of Jacksonville’s shipbuilding legacy trace back to the 1850s, when Jacob Brock established the first shipyard on the site now commonly known as the former Jacksonville Shipyards. Following Brock’s death in 1877, the shipyard was sold to Alonzo Stevens. In 1887, Stevens partnered with James Eugene and Alexander Merrill to form the Merrill-Stevens Engineering Co.

By 1918, the shipyard had grown significantly, employing around 1,500 workers and boasting the largest dry dock on the East Coast between Newport News and New Orleans. During this era, the shipyard played a notable role in global infrastructure—constructing the barges used in the building of the Panama Canal.

In the 1950s, Merrill-Stevens sold the Jacksonville operation and relocated to Miami, where the company continues to build yachts today. In 1963, the site was purchased by W.R. Lovett, who renamed it Jacksonville Shipyards, Inc. Under his leadership, the shipyards flourished and became Jacksonville’s largest civilian employer, with a workforce of 2,500 before being sold to the Fruehauf Corp.

The decline of the shipyards began in the 1980s, culminating in a temporary shutdown in 1990 that resulted in the layoff of 800 employees. Although it briefly reopened, the shipyard permanently closed in 1992 after selling its dry docks to a shipyard in Bahrain—resulting in an additional 200 layoffs. The historic shipyard buildings, which had once symbolized Jacksonville’s industrial strength, were demolished in the early 2000s.