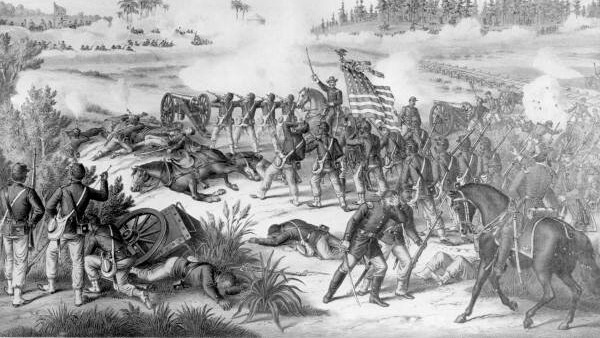

War is hell. But at Olustee, war is treated much like a county fair.

Every February about 48 miles west of Jacksonville, the Battle of Olustee reenactment is an occasion for lots of fun. This year the battle reenactment will take place from Feb. 14-16, with the festivities on Friday and Saturday. Besides a battle reenactment, there will be craft vendors, a fun run, a battle of the bands, the crowning of Miss Olustee and more.

One-hundred-sixty-one years ago, the actual Battle of Olustee was the largest Civil War battle on Florida soil, on Feb. 20, 1864.

Union forces left Jacksonville and moved inland for four reasons: (1) to procure supplies for the Union; (2) to prevent supplies from reaching Confederate forces; (3) to obtain African American recruits for the Union Army; and (4) to restore Florida to the Union, which could include participation in the 1864 presidential election. Abraham Lincoln had not been on the ballot in Florida and most Southern states in 1860.

Battle reenactments, with their theatrical fire and fury, typically emphasize acts of courage and, in the spirit of unity, occasional acts of kindness. For instance, my ancestor, Edgar W. Clark of the 3rd Michigan Infantry Regiment, wrote to his wife that he delivered water to wounded Union and Confederate troops after the Battle of Gettysburg.

But important aspects of the Battle of Olustee are much darker. Confederate soldiers at Olustee killed wounded African American soldiers rather than allow them to be captured. Thus, Olustee is linked in infamy with Poison Spring in Arkansas, Port Hudson in Louisiana and Fort Pillow in Tennessee.

Apologists for Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest have argued that he was not responsible for the atrocities documented at Fort Pillow in a congressional investigation. Well, there are only two explanations: Either he ordered the killings of wounded men or he was such a poor leader that he lost control of his troops. Similar excuses have been made for what happened at Olustee.

African American units who fought at Olustee included the 54th Massachusetts, the famed unit in the movie Glory. They protected the Union retreat back to Jacksonville.

Both Union and Confederate sources documented the Olustee casualties. For sheer violence, the proportion of casualties at Olustee was huge — more than 1 in 4 killed, wounded or missing— 2,807 casualties of the more than 10,000 troops. Most of the casualties were from Union forces — 1,861 Union casualties to 946 Confederates.

But the shocking statistic relates to missing soldiers: 506 missing Union soldiers to just six missing Confederate soldiers, a difference of 84 to 1. Why were there so many missing Union soldiers? In his after-action report, Union Brig. Gen. Joseph Hatch wrote, “It is now known that most of the wounded colored men were murdered on the field.”

This is one of the reasons that the Confederates failed to follow up their Olustee victory. Rather than attack the retreating Union forces, they were busy slaughtering the wounded.

Sanitizing the Civil War by eliminating racial references distorts history. By the summer of 1864, Union forces had been ground down by massive casualties. Consider my ancestor, Edgar W. Clark. By the summer of 1864, the riddled 3nd Corps of the Army of the Potomac had been merged into the 2nd Corps, the riddled 3rd Michigan Infantry Regiment had been merged into the 5th Michigan, and Edgar’s riddled Company G was down to just eight men. Most Union soldiers were not reenlisting.

As David Williams, retired history professor at Valdosta State University, wrote in his People’s History of the Civil War, there were multiple draft riots throughout the North, not just in New York City. Also, almost 100,000 draft-eligible Northerners fled to Canada. Then there were the insurance pools in which young men contributed money so that one of them, if drafted, could pay $300 for a replacement.

Without African American troops in the Union Army, President Abraham Lincoln wrote, the war would be over in three weeks. “There have been men who have proposed to return to slavery the Black warriors of Port Hudson and Olustee,” Lincoln wrote. “I should be damned in time and in eternity for so doing.” Those African American soldiers were ferocious because they were fighting for their freedom and they knew they were unlikely to be treated like other prisoners.

Granted, a minority of Confederate soldiers committed these acts of battlefield cruelty, but in many cases they weren’t being stopped. Also, some African American soldiers responded in kind by “giving no quarter” to wounded Southern soldiers.

After Olustee, there were two more shocking examples of brutality in Jacksonville. Just as the war ended, Union prisoners at Andersonville, Georgia, were sent to Jacksonville. As Daniel Schafer wrote in his book, Thunder on the River: The Civil War in Northeast Florida, the former prisoners arrived in appalling condition — faces grimy with dirt, feet sore from marching without shoes and suffering from scurvy. The editor of the Florida Union newspaper wrote, “Jacksonville has often been the scene of many of the terrible realities of the war, but never were the people so appalled with the horror as when the released Union prisoners arrived in our midst.”

After the war in 1866, a Union officer examined the graves at Olustee. He found Confederate graves in perfect shape but Union graves in such poor condition that hogs had dug into them — bones and skulls were scattered over the battlefield.

The racial aspect of this story makes many white people uncomfortable. Historian Gregory G. W. Urwin wrote that the desire to whitewash Civil War history has been prevalent in the North as well as the South. In his book Black Flag Over Dixie: Racial Atrocities and Reprisals in the Civil War, Urwin wrote, “The Civil War was not the chivalrous contest that white America prefers to remember.”

Urwin wrote, “Many of the middle-class white males who populate Civil War roundtables and reenactment groups prefer their history without African Americans in it. … A vicious and bloody conflict is now remembered as an ennobling experience.”

Poet Walt Whitman, who worked in Union hospitals in Washington, D.C., wrote, “Future generations will never know the seething hell … of the Secession War and it is best that they do not — the real war will never get in the books.”

It is our job to tell the true story of the Civil War. Turning horrors into entertainment does a disservice to history.

Postscript: More confirmation

The editor of Jacksonville Today asked for recent photos of an Olustee reenactment. I made several inquiries and was referred to a park ranger. The park ranger at first said there was a photo, but once I mentioned the thrust of the column, it was like throwing a skunk into a garden party. The park ranger questioned the accuracy of the killings of wounded Union soldiers, so I offered to take a look at any contrary evidence. Meanwhile, I emailed the same request to the Olustee Battlefield

Citizens Support Organization, which supports historic interpretation at Olustee Battlefield Historic State Park and runs the Battle of Olustee website. I have not heard back.

So I took another look at their website, and I found this: “A regrettable episode in the aftermath of the battle was the apparent mistreatment of Union black soldiers by the Confederates. Contemporary sources, many from the Confederate side, indicate that a number of Black soldiers were killed on the battlefield by roaming bands of Southern troops following the close of the fighting.”

Also on the Battle of Olustee website, there was a story that noted that the Olustee Battlefield Historic State Park was selected as a recipient of the 2003 Congressional Black Caucus Veterans’ Braintrust Award, which recognizes “exemplary national and community service on behalf of African American veterans.”

That story included this statement: “Letters written by the soldiers and historians’ reports afterward have lauded the heroism of the 35th USCT and the 54th Mass in holding the rear guard against the Confederate Army while the rest of the Union soldiers retreated. The African American regiments were aware that Black troops left wounded on the battlefield were being murdered by Confederate soldiers, but the regiments continued fighting until after dark. An estimated 626 members of the Black regiments were killed, wounded and captured, representing one-third of the total Union casualties for the battle.”

It is worth noting that not every wounded Black soldier was killed on the battlefield. Some were captured and sent to the Confederate prison at Andersonville. Small consolation, but at least they had a chance of survival.

Mike Clark devoted about 47 years to Jacksonville's two daily newspapers. He retired in 2020 after 15 years as editorial page editor at The Florida Times-Union, where he and his staff won local, state, regional and national journalism awards.

He is the author of the new book, “Civil War Survivor: Incredible True Story of a Union Private.”