Abolitionist and 19th century author Harriet Beecher Stowe has returned to Mandarin after a 140-year absence.

But it took a few tries to get her seated correctly Friday on a granite bench at Walter Jones Historical Park in Mandarin, so she could teach writing to two little boys who worked on her farm back in the day.

The life-size bronze sculpture of Stowe and the children was installed outside the park’s restored 128-year-old St. Joseph’s Mission Schoolhouse for African American Children at the historical Park. It was once where the children of former slaves were educated by Catholic nuns when it was first built in the nearby village of Loretto.

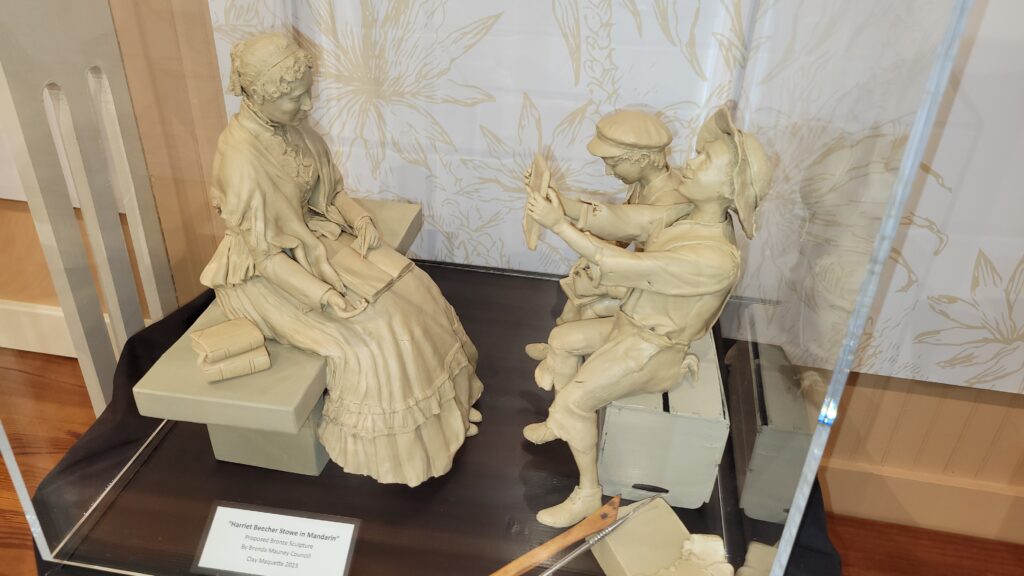

Artist Brenda Councill began the piece as a clay sculpture last winter. It was then cast at Carolina Bronze in North Carolina before shipment to Jacksonville this week. As she watched Carolina Bronze’s Nichole and Adam Kennedy do the final fettling of the sculpture on Friday, Councill said she is thrilled that this piece of history will be officially dedicated at 3 p.m. on Sunday, Nov. 17, at the park at 11964 Mandarin Road.

Still wrapped in padding and plastic to protect the work on its trip to Jacksonville, only some of Stowe’s voluminous skirt was visible as the Kennedys carefully installed it on the bench.

She now sits just up the road from where the Uncle Tom’s Cabin author lived post-Civil War.

“I felt like it was not enough just to have plaques on the side of the road signifying the landmark cottage where she lived,” Councill said. “I felt that it was important for the generation now, and generations in the future, to come sit with Harriet Beecher Stowe, have an interaction with her, and understand her impact and legacy here.”

“Beyond excited” at the sculpture’s completion and installation, longtime Mandarin Museum and Historical Society member and current board Vice President Sandy Arpen said the piece offers a slice of what daily life could have been for Stowe.

“Harriet was such an important figure to this community and to Jacksonville. She really brought changes here that we needed after the Civil War,” Arpen said. “… As far as we know, it is the only full-scale sculpture of Harriet in existence. There is a small sculpture of her up in Hartford, and a bust in Cincinnati.”

Stowe was a Connecticut resident who lived in a Mandarin Road cottage every winter from 1867 through 1884, across the St. Johns River from her son Frederick’s cotton farm in what is now Orange Park. She shared the home with her husband, the Rev. Calvin Stowe, who helped found the nearby Church of Our Saviour. Stowe also helped the Freedmen’s Bureau found a school for African American children in Mandarin, purchasing the land and hiring the first teacher, in what is now the Mandarin Community Club at 12447 Mandarin Road.

“She did write a lot – she wrote Palmetto Leaves, she wrote numerous pieces about her time in Florida and her work with the community here,” Councill said. “… Her impact here was enormous.”

Less than a mile east of Stowe’s long-gone cottage, the Historical Society opened its facility in 2004 at the main entrance to the city’s Walter Jones Historical Park. The museum fronts part of a 10-acre farm started in 1873 by U.S. Army Maj. William Webb, then taken over in the early 1900s by Mandarin postmaster Walter Jones. In 1911, Jones opened his store and post office next to the community club, both across from Stowe’s long-gone winter home.

The restored 113-year-old Historic Mandarin Store & Post Office at 12471 Mandarin Road, operated by the historical society, is where Councill began sculpting the clay version of the statue from last December through February. The North Carolina artist let visitors to the general store museum watch her at work. She noted the design included “the underage children, who, sadly, would have been employed in her orange groves.”

The sculpture is two pieces. One bronze casting, about 250 pounds, is Stowe seated in a flowing skirt, a lesson book in her lap. The other part, about 350 pounds, are two boys seated on an orange crate. Child laborers in her orange grove, one proudly shows a slate that reads “I am Eli.”

With Stowe living across from the Freedman’s Bureau, the sculpture shows something that could have happened 140 or more years ago, possibly as she taught Sunday School.

“She comes out of her house to encourage them to go across the street to the school she helped to start and get their education and how to read and write,” Arpen imagines. “That was the whole idea, that she was encouraging the whole population, black and white, to get an education and learn the basics.”

The idea to create the sculpture was approved by the city and Florida Communities Trust, its $170,000, cost paid for from donations from the community and elsewhere.

Now covered by wrapped plastic sheets, the two spotlit statues will be unveiled on Sunday, along with a special exhibit inside the historic one-room schoolhouse nearby with time-lapse video of Councill’s sculpting and Friday installation and more information on Stowe.

“People will actually be able to see the process of Brenda Councill’s sculpting from Day One to the finished product,” Arpen said. “It is absolutely amazing process to watch someone put fingerfuls of clay onto something and have it turn out to be Harriet Beecher Stowe and two little boys.”

“It’s very emotional; it’s very pleasing that this moment has come without any mishap, and I couldn’t be more pleased,” Councill added.

There is also more displays about Stowe, plus the original sculpture design maquette, on display inside the Mandarin Museum along part of the decorative woodwork that once graced her Mandarin cottage.

More information on the project can be found at mandarinmuseum.org.