Q. Proposed amendments to Florida’s Constitution have caused a stir this election cycle. While the primary focus has been on amendments surrounding cannabis and abortion, an amendment involving public funding for campaigns is raising questions too.

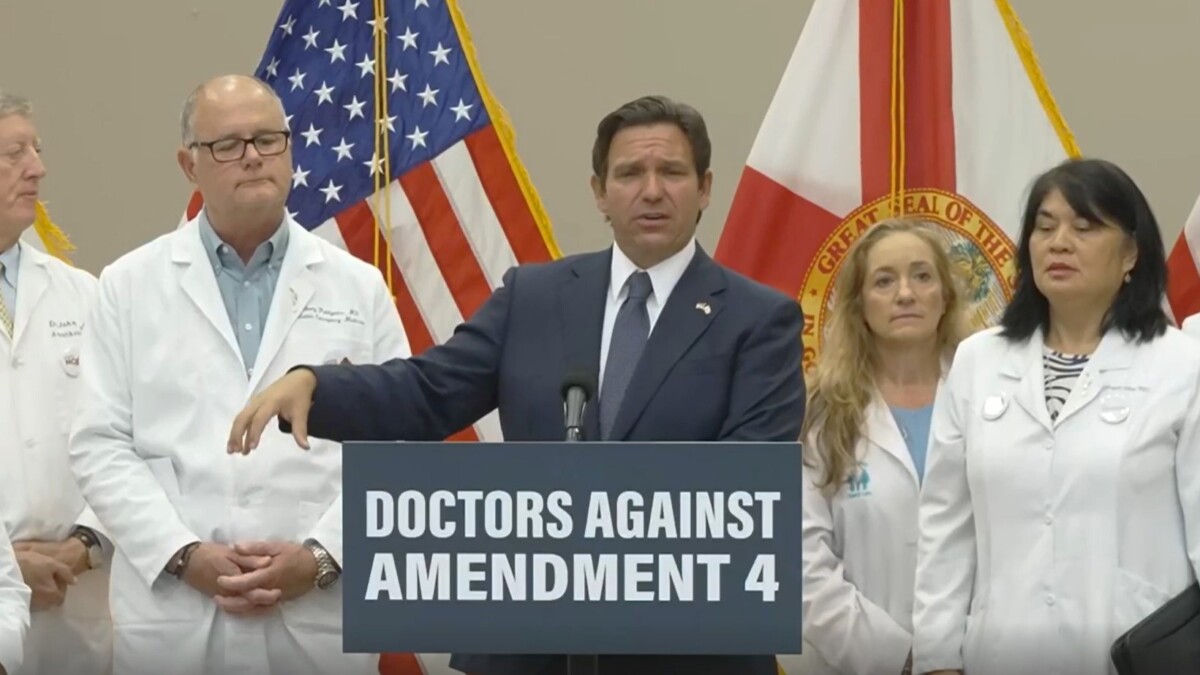

Jacksonville Today reader Matthew S. wants to know how a mechanism for candidates who lack funding led to Gov. Ron DeSantis receiving millions in taxpayer dollars for his 2018 and 2022 gubernatorial campaigns.

Matthew asks:

“I see that DeSantis took $7.3 million in 2022, which is a total much higher than any other candidate. I can’t seem to find how or why this is the case. Are you able to explain this or provide any resources that might?”

A. Campaign funds are top of mind because of Amendment 6 on the Nov. 5 ballot. That amendment asks whether voters want to do away with a pot of money that has provided public campaign funding for statewide candidates.

In 1998, voters approved a constitutional amendment that, among other tweaks to election rules, sought to level the playing field for candidates who are not independently wealthy or supported by special interest groups.

The approval of Amendment 11 created a public funding mechanism where, if candidates for governor and other statewide offices stuck to a handful of rules surrounding funding for their campaigns, they would be eligible to receive state funds matching some donations.

READ MORE: Learn about Nov. 5 ballot issues in the Jacksonville Today Voter Guides

Money for the fund comes from the fees candidates must pay to qualify to run and other state-assessed charges to campaigns. If necessary, state statute notes that additional funds from the state’s revenue can be added.

Money provided to campaigns that follow the state’s guidelines is determined by their donations. Donations of $250 or less from Florida residents are eligible for matching funds from the state.

In 2022, state candidates received a total of $13 million from the public campaign finance fund, and the incumbent DeSantis was the recipient of more than half — $7,302,617.03 — of that.

But he received more funding for his campaign because he out-fundraised his opponents by a sizeable margin.

Funding rules

To be eligible for public funds, as of 2022, candidates have to stick to the following limits:

- A candidate must have at least one opponent.

- Candidates for governor can’t spend any more than $2 per registered Florida voter from their campaign coffers, and candidates for cabinet officers like the commissioner of agriculture can’t spend more than $1 per registered voter. That means candidates for governor in 2022 were limited to spending $30,286,714.00, while candidates for cabinet offices were limited to spending $15,143,357.00.

- Candidates for governor must raise $150,000 from Florida residents, while cabinet officers must raise $100,000.

- Candidates can’t contribute more than $25,000 of their own money to a campaign, and donations “from national, state, and county executive committees of a political party” can’t exceed $250,000.

- Lastly, candidates must provide the state Division of Elections detailed financial reports and participate in a post-election audit of their campaign.

With those rules in mind, let’s take a look at DeSantis’ 2022 campaign.

For starters, DeSantis definitely had opponents — chief among them were Democrats Charlie Crist and Nikki Fried, both of whom also received funds from the state’s campaign finance fund. Crist received $3,887,559.53, while Fried took home $944,850.26.

DeSantis also kept his campaign expenditures under the required amount. His campaign spent $25,756,294.20, about $5 million under the spending limit.

As for donations from Florida residents, DeSantis cleared that hurdle during his first month of campaigning in 2021. And while the DeSantis campaign received millions of dollars in donations from the Republican Party of Florida, those donations were in-kind contributions, which are not prohibited in the state’s regulations.

The debate about funding

If approved by at least 60% of voters, Amendment 6 would eliminate this public funding option for campaigns.

Amendment 6 made it to the November ballot thanks to a measure passed by the Florida Legislature earlier this year. Support for the bill largely fell along party lines with Republicans supporting bill sponsor Travis Hutson, R-St. Augustine, and Democrats arguing that public funding for candidates plays an important role.

Hutson opposes public funding of any kind for candidates and wanted to bring the question back to voters this year. Meanwhile, even if candidates from all political parties can benefit from the money, Democrats like Sen. Tina Polsky, D-Boca Raton, think the funding option should remain in place.

Speaking before the Florida Senate Committee on Ethics and Elections earlier this year, Polsky said whether it was Hutson’s intention or not, Republicans would be least affected by doing away with the fund.

“It is very clear the Republican Party has a lot more money, funding, outside groups, special interest groups, who help pay for campaigns than the Democratic Party has in Florida,” Polsky said. “And as a result, it seems that this would be a negative for Democratic candidates, because if this passes, and the voters vote for it, they wouldn’t have the option for public finance which, at this point, they need more than the other party.”