Death and taxes are usually held up as the avatars of inevitability, but right beside them are unintended consequences from Florida laws.

Exhibit A: HB 1365, affecting Jacksonville and other cities in this market, banning public camping and sleeping. Lawmakers approved it during this year’s legislative session and it’s been in effect since the first of this month.

Those who recall the legislative process will remember the aspirational rhetoric from the local legislative sponsor and the governor of our state.

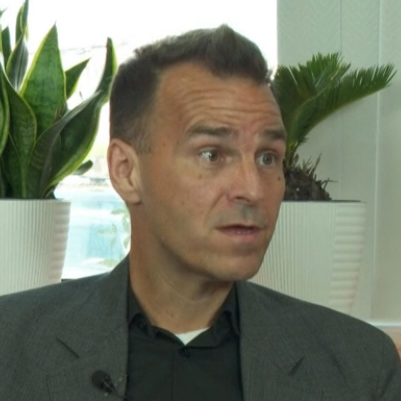

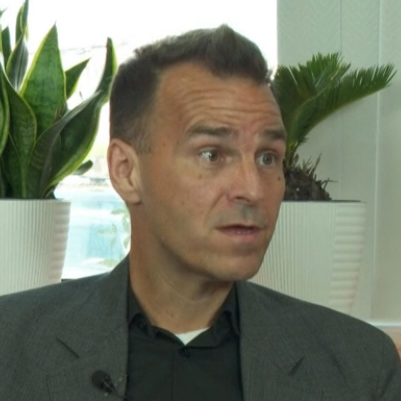

Sponsoring Rep. Sam Garrison, the future House Speaker from Clay County, framed the law as a “Florida model” for dealing with the unhoused, a “carrot and stick” approach designed to disincentivize sleeping rough, with the end goal being to clear the streets of them.

Ron DeSantis offered some guidelines to help shape the legislation along the way, saying the area that cities relocate people to “can’t just be some site that is like Sodom and Gomorrah, where they’re using drugs and doing all this stuff” and that help must be available.

When he signed the bill, DeSantis proclaimed it “will help maintain and ensure that Florida streets are clean and that Florida streets are safe for our residents.”

DeSantis has spent years dining out at the expense of the unhoused, of course. When he was running for president, he made a habit of brandishing a “poop map” of San Francisco streets, a sort of coprophiliac Rorschach Test.

He also told folks in Iowa last winter that the unhoused should be locked up, given that “some of these folks would benefit from being in an institutional setting and I think the public as a whole would be safer as a result of them being in an institutional setting.”

In the interest of perhaps helping the unhoused, the legislation requires “behavioral health services, which must include substance abuse and mental health treatment resources.”

Is Jacksonville complying?

Sorta kinda.

The idea of social services aside, the state law is intended to be punitive: to drive localities to get homeless people off the streets and into a centralized location.

Jacksonville’s model elides the “discipline and punish” motif though, raising questions about how compliant the local model is with the state intent.

The local ordinance (2024-713) passed in September “appropriates $2,500,000 from a Homelessness Initiatives Special Revenue Fund Designated Contingency account to the Jacksonville Fire and Rescue Department for implementation and administration of a Homelessness Strategic Plan for Duval County.”

The measure greenlit seven full-time positions within JFRD for a “homeless persons EMS response team.”

“We’re grateful that JFRD has stepped up really an elegant solution to the teams that we need to make contact with these folks,” Deegan said, via First Coast News.

Hilariously, given that this is the freest spending mayoral administration in Jacksonville history, with a stadium spend that subsidizes the business interests of an out-of-town billionaire whose team started out the season with a month of consecutive losses (before beating the Colts’ backups on Sunday), and new pension plans for first responders despite roughly $5 billion in unfunded pension liability for a plan closed down nearly a decade ago, money’s tight when it comes to following the state homelessness mandate.

“We need more money. There’s no question that we do,” Deegan said, again via FCN. “We’ve started off with a minimal amount of funding right now and as we go, it’ll get us started. But as we go, we’re gonna need to add more to that.”

Why is JFRD, which does not have enforcement power when it comes to violating the law, charged with dealing with this problem?

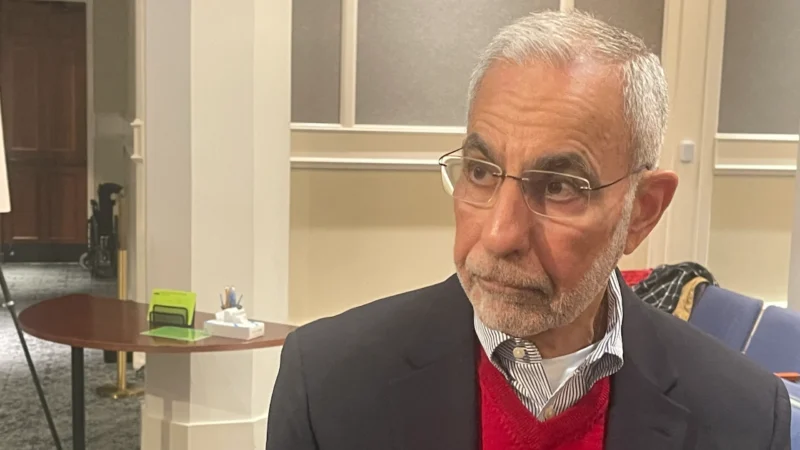

Because, ultimately, city officials, even DeSantis Republicans, seek to flout state legislative intent, as San Marco City Council member Joe Carlucci’s statement to WOKV makes clear.

“We don’t want to be putting them in jail. That’s not the goal. The goal is to first make sure they’re okay and then the goal is what services can we provide to them,” Carlucci said, ignoring the reality that Tallahassee wants the homeless off the streets and out of sight because, whether city leaders like it or not, state Republicans see the transient population as an affront to quality of life for taxpayers with jobs, homes and a stake in the community.

Deegan also says apprehension by law enforcement is a last resort, as Action News Jax reported in July.

Estimates of how many unhoused people there are in Jacksonville are fragmentary, but the problem is growing. At least 566, according to Changing Homelessness. That number from 2023 was up more than 40% from the previous year.

Jacksonville’s approach is all carrot and no stick, to use Garrison’s framing, and it’s not certain how a seven-person fire and rescue team will deal with the downstream problems posed by the increasing issue seen in a number of key neighborhoods — particularly Downtown, as evidenced by this year’s decision by Citizens Insurance to move to the Southside because their employees didn’t feel safe in the Urban Core.

It’s not just Downtown though. Consider Five Points, which has seen an exodus of businesses in recent months for various reasons. But that doesn’t mean the storefronts are empty. While the Five Points Theater is long gone, there’s still a show of sorts, as a walk down Park Street compels pedestrians to deal with increasingly persistent panhandlers.

Are locals supposed to call JFRD to deal with the issue, since the mayor doesn’t think cops have any role in enforcing the law?

Or are they supposed to wait on Deegan and a lapdog City Council to jack up property taxes to get the money they programmed elsewhere in their Supermarket Sweep approach to municipal finance, secure in the knowledge that this increasingly is a city of renters who don’t care what happens to millage?

Yes, the mayor is correct in blasting the law as an “unfunded mandate.”

But she makes the same mistake relative to DeSantis edicts that the governor does regarding federal mandates: forgetting the reality of being a subsidiary of state government that ultimately has to abide by a top-down approach.

Jacksonville’s approach to the law ultimately will be tested by the civil action plank in the state statute, as residents and business owners (people with property interests and skin in the game) who don’t think the city is doing its job with this half-hearted implementation will be able to sue starting Jan. 1.

Perhaps aggressive litigation will be the dash of cold water that the city needs to actually enforce the law as the state intended. At the very least, it will give the Office of General Counsel something to do.