This week, four Jacksonville children will learn about the Tulsa Race Massacre because of a Grammy-nominated funk group.

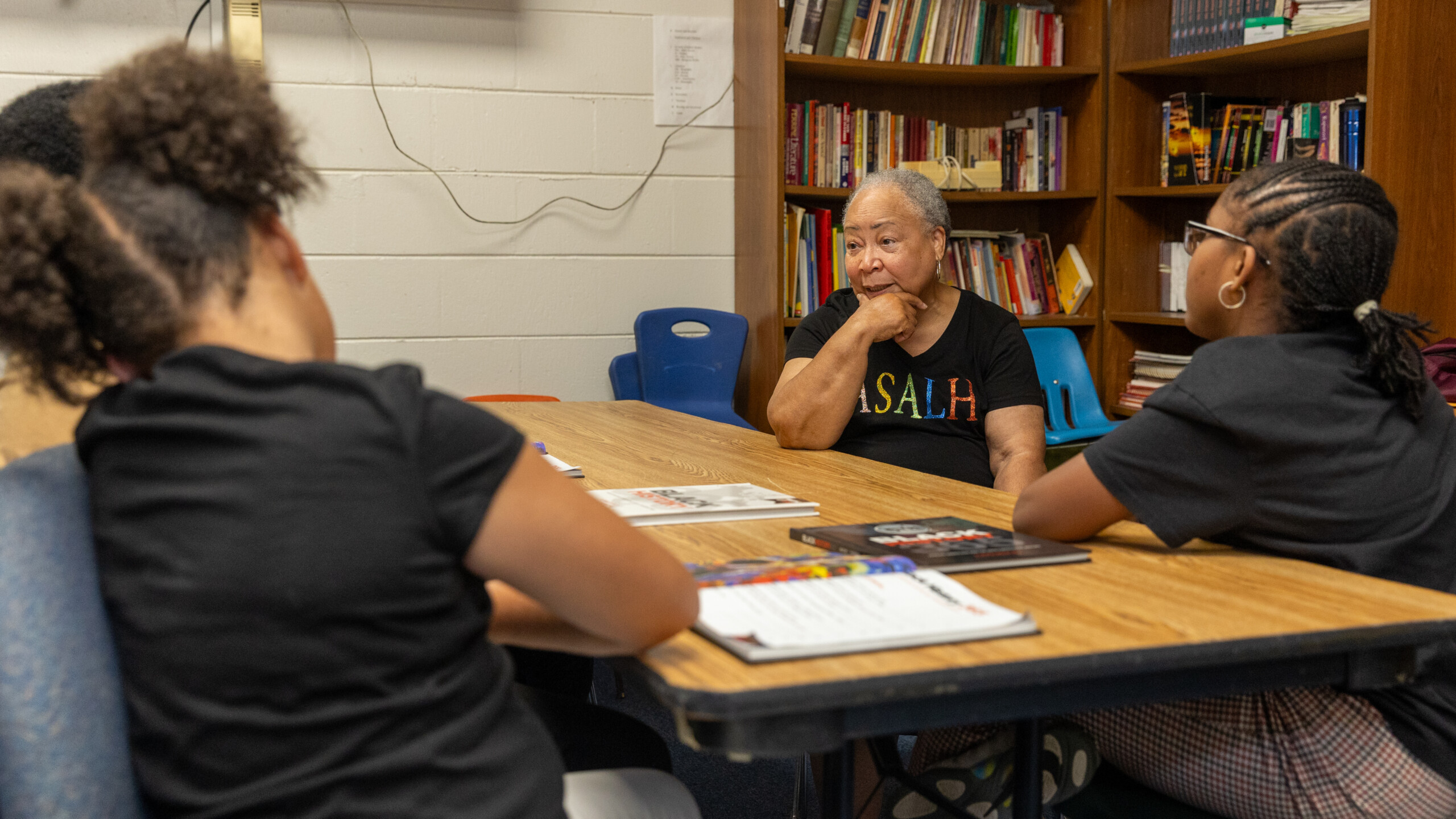

That was Christine McNair’s challenge to the students during the orientation of a local Black History Freedom School.

The James Weldon Johnson Chapter of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History created a Black History Freedom School to help school-aged children, and their families, learn about Black history. A pilot program was launched in February. A seven-month curriculum kicks off Saturday.

McNair is a retired teacher and guidance counselor who will serve as one of the educators within the Freedom School.

The school is free. It meets on Saturday mornings inside Mt. Sinai Missionary Baptist Church in Springfield.

“I’m just thrilled,” McNair says. “There’s a lot of history, a lot of events that have taken place, that children may or may not know about. In order to get our history to stay alive, we need to engage them. That’s bringing me joy to be able to do that.”

There have been multiple attempts to create a Freedom School in Jacksonville. Those efforts intensified after the Florida Department of Education released social studies standards for middle school students last year.

The standards say students in grades 6-8 should have instruction that includes “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

Gundy resigned from his teaching position at Ribault Middle School last year after the standards were released. Today, he says it’s important that young people — regardless of their race, gender or ZIP code — should know the history of everyone.

“There is no Black history without American history,” Gundy says. “There is no Black history without Florida. It’s not just Jacksonville. It’s not just Blacks. There were inclusive cultures that helped that history. It was poets, writers, actors, military personnel who existed (here). It’s important if we want to help young people know who they are, give direction and hope that they (may) know their own history.”

The James Weldon Johnson ASALH chapter’s Freedom School uses Black History 365: An Inclusive Account of American History textbook. That text has been incorporated in more than 40 school districts in Texas; in Portland, Oregon; in Detroit; in Palm Beach County as well as rural districts. It’s also used by Freedom Schools in Tampa, St. Petersburg and Sarasota.

Walter Milton Jr. co-authored the textbook. Milton told Jacksonville Today in September 2023 the textbook embeds QR codes into pages as well as other technologies to capture students’ attention.

“One thing about our work: it doesn’t denounce anyone to elevate another group of people,” Milton says. “It really recognizes all of those people that have contributed to our liberation.”

Milton believes children should be intrinsically educated. Doing so would stimulate learning.

“Education creates deep thinkers,” Milton says. “It’s important to help students become critical and analytical thinkers. When they have those skill sets, they can do well in life. We have to tie in who they are as cultural beings, what that means to the world and the impact that their ancestors have contributed to society.”

Edna Sherrill is an educator at Booker High School in Sarasota. She’s also one of the educators for the ASALH Manasota Freedom School.

Sherrill says Freedom Schools are possible because there are people who know and love Black culture and people who love children enough to tell them the truth.

“Several of our students noted they didn’t know there was so much resistance to what was happening,” Sherill told Jacksonville Today in September 2023. “You could use enslaved people, you could use the Little Rock Nine — our students didn’t know how many people pushed for so long to make sure we have the freedom and justice and all (that) we’ve heard about in our classes.”

Sarasota’s Freedom School begins in February to coincide with Black History Month. St. Petersburg holds its 10-week Freedom School in the summer.

Sherrill says the key to a successful Freedom School is incorporating the needs of a community. That’s why Sarasota incorporates the arts into its Freedom School discussion. Jacksonville’s Freedom School will lean on local history.

The schools McNair taught at during her career — John E. Ford PK-8 Montessori School and A. Philip Randolph Career Academies, two schools named after men whose impact was felt in Jacksonville and throughout America — illustrate the region’s robust Black history.

During Saturday’s orientation, Hazel Gillis, president of the James Weldon Johnson ASALH branch, wore pears with a Black T-shirt with white letters that said: “Freedom School Program.” Later, she thanked the students, and their parents, for their attendance.

“We are all here to learn,” Gillis says. “We don’t know it all. We will be able to learn our history.”

Gillis and Juanita Powell-Williams, the chair of the local ASALH chapter’s Freedom School committee, did not know the answer to McNair’s challenge to the students.

It turns out the Grammy-nominated group is from Tulsa, Oklahoma. Their name is an acronym for Greenwood, Archer and Pine — streets in their hometown that were destroyed by a white mob in 1921.

The Tulsa Race Massacre was a riot that destroyed a wealthy Black community after a disturbance on an elevator between a Black man and white woman that was sensationalized by local media.

McNair acknowledged she may not know a lot of the GAP Band’s songs, but the idea of receiving knowledge, verifying its accuracy and sharing it with another generation was too enticing to ignore.

Gundy says longtime Jacksonville activist Rodney Hurst as well as local author and March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom attendee Marsha Dean Phelts are among those who will speak with students in the Freedom School.

Florida has mandated that African American history is taught in elementary and secondary schools for the last 30 years. McNair says there is more to explore. And that’s the gap the Freedom School will close.

“There are so many people that have contributed that don’t get recognized,” McNair says. “They may not have done it for recognition, but we need to know.”