Some might say that oyster shells and pottery shards buried a thousand years ago are just garbage.

But to a group of archaeology students who are uncovering them in the Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve, they are true treasures.

The students from the University of North Florida are sifting through refuse mounds to piece together the history of a people who lived along the Intracoastal Waterway long before the first Europeans set foot here.

“I like learning about the past and learning about indigenous history, so it has always been just trying to learn more about the place we live in. To me, history extends back beyond European arrival,” said UNF Archaeology Lab Director Keith Ashley. “We have an incredibly deep indigenous history here in Northeast Florida, and I want to help try to bring that to life and bring that to more people.”

Ashley has led about 20 students through this summer’s excavation of midden mounds — Timucuan Native American garbage piles full of oyster and clam shells. Student Amelia King realizes they are digging through ancient garbage, but it can tell us who these people were, she said.

“There’s no written records that we can just read straight from the source that tells us ‘my name is this, and I lived here and I did this every day,'” she said. “Utilizing what we dig up can give us some important context, and just more than what we have. Anything more is great.”

UNF student archaeologists have been examining Native American sites around Jacksonville for more than 20 years during annual six-week summer field trips.

In 2022, Ashley and earlier students investigated Mocama tribal sites dating back to the 1400s off Heckscher Drive, excavating what appeared to be a 50- to 60-foot-diameter community council house in the village of Sarabay. This summer’s dig is looking further into the past and the Timucua tribes that lived north of the St. Johns River near what is now Pumpkin Hill Creek Preserve east of Yellow Bluff Road.

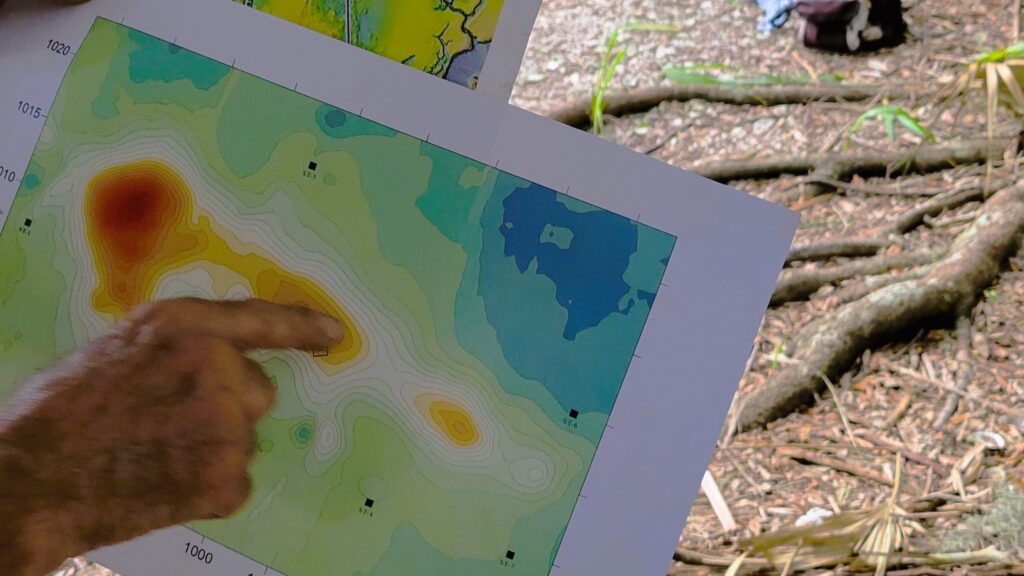

Ashley decided to focus on this site after aerial survey maps showed interesting features on some creek shorelines. Walking the sites revealed shell mounds and ridges now encased in a forest, of dense palmetto trees and vines. So this year’s Archaeological Field School is getting hands-on experience exploring the Timucua’s midden mounds and ridges, dating to the 11th to 13th centuries.

“This is for them to get practical experience. A lot of them want to be archaeologists, so this is their first kind of experience in the field,” Ashley said. “A lot of times, what we encounter in the field is really different than what you read about in the books. The books are really the ideal situations, ideal settings. Here, they get to directly touch the past and see how archaeology is practiced in America.”

Students learn basic field techniques, including survey shovel testing, excavation, mapping, record keeping and the use of survey and mapping equipment. This year’s program will run through June 21.

First, students worked in early June at the Yapi site, named for the Timucuan word for palmetto, part of a series of midden mounds on sites off the Intracoastal Waterway. A deep trench was cut into one mound of debris discarded by the people as they sorted through fresh oysters, clams and other seafood they had caught.

During their second week, students began working the Iyola (snake) site just south of the Yapi dig, where survey maps show that the midden mounds are very different from ones found in the past, Ashley said.

“Usually they are just piles. But here, they really have shapes to them. They are really long and linear. They have mounded areas; they have kind of comma shapes,” he said. “It is really unique that they are disposing their garbage this way. We are not sure if these are mere piles of garbage, or it’s something architectural, or some sort of hidden kind of meaning to them.”

So far, no sign of the homes where these people lived has been found, he said. It is unknown whether these midden mounds were part of a village or a rendezvous point for other villages specifically for food gathering.

Whatever it is, excavating all these mounds is hard work, as students dig multiple test trenches into the sharp-edged oyster and seashell mounds, then carefully sift through what is in them with garden tools, hunting for pottery shards and preserved bones, some as tiny as a fingernail.

Every trench’s contents is poured into buckets that are then sorted by students in boxes with screens underneath. Fish bones and smaller pottery shards are found, then carefully wrapped for further study. Sorting tables like these helped find two tiny jaw pieces complete with teeth during the Mocama excavation two years ago, possibly the remains of a 16th-century meal.

“We need to learn more about native people in Northeast Florida. There is not a lot that has been done, and it is important to continue cultural research about them,” King said. “I have not done a field school yet, and I am going to get my master’s in archaeology this fall at FSU, so I had to get some experience.”

During a recent excavation, a cheer went up as a large piece of “check-stamp” pottery — so-called because of the pattern embossed in it — was found. It was part of a large bowl with a flattened bottom, blackened where it had sat on a cooking fire.

Nearby, student Shawn Steiner was on his knees checking through the shells in a 6-foot-long trench when he found multiple pieces of pottery.

“We are digging through their big trash pile and what they left behind, but you can learn a lot about a civilization from their trash,” Steiner said. “Look at our trash — you can learn tons of things, so that is what we are trying to do: understand the people who were here, what they were eating and what this site was in relation to other sites around town.”

As she held a piece of pottery she found earlier that day, King had the same feeling.

“One of the great things about archaeology is that it is a sub-field of anthropology, so we are interested in people,” King said. “And just what some people might consider the mundane — their everyday life — just being able to hold this and know that someone used it and maybe just something simple in everyday life is incredible.”