Shed Dawson didn’t want to come back to St. Augustine.

St. Augustine is where he was arrested. It’s where he was beaten. And it’s where he left because he was blackballed out of finding a job.

And Dawson was all too aware that last year, not far from St. Augustine, a white supremacist murdered three Black people in a racist shooting at a Dollar General store in Jacksonville.

Despite all of that, Dawson came back to St. Augustine to share stories from his life.

He was joined Wednesday by fellow St. Augustine natives Purcell Conway and Thomas Jackson at the opening of Waves of Change, a new outdoor museum exhibit at the historic St. Augustine Beach Hotel that aims to educate people about the building and the beach’s connections to the Civil Rights Movement and the 1964 Freedom Summer protests.

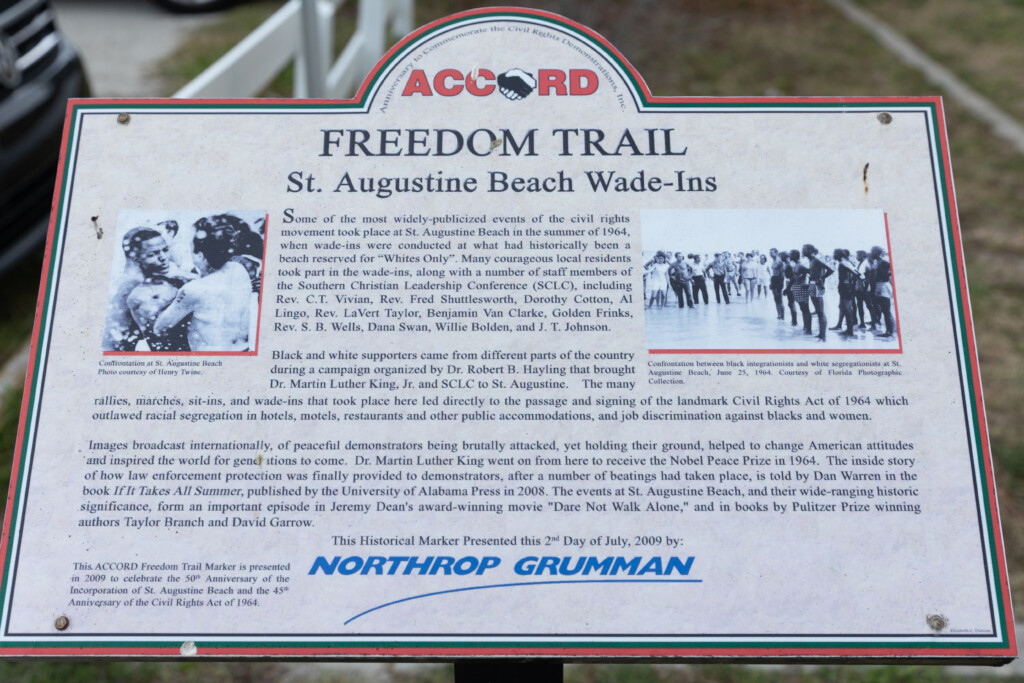

Built in 1940, the building overlooks a stretch of beach that was the site of wade-in protests, where Black beachgoers tried to dip their toes into the surf of the “Whites Only” beach just a few miles from Butler Beach, designated “Blacks Only.”

“Butler Beach was the Black beach,” Jackson recalls. “You could only go so far south on Butler Beach. Folks would tell you not to go any further or there’d be trouble.”

So, in 1964, Black locals and visitors alike organized a protest at St. Augustine Beach. They were met with angry, violent counterprotesters as well as a sea of state troopers there to break up any violence that broke out.

“There was a large crowd of protesters out there, heavily armed,” Conway says. “Baseball bats, iron pipes, chains …”

It didn’t take long for the violence to start.

“The melee that took out in that ocean — I’ve never seen such violence,” Conway says.

When the dust cleared, Conway remembers that the sand was stained red. But the thing that stuck with him the most was that he couldn’t remember another time when he’d seen white men beating up other white men.

Episodes like that are just some of the stories men like Conway, Dawson and Jackson carry with them all these years later. Jackson, 71, was younger than the rest, but Conway, 75, and Dawson, 77, were teenagers participating in the protests because, the men said, they felt they had no other choice.

“There was no future for me as a young Black man in St. Augustine, Florida,” Dawson says. “I knew if I got involved in the demonstrations, it could ruin my life. I had no way of knowing how it would affect me and my life if I got involved.”

Dawson was entering his senior year at Richard J. Murray High School, but word came down from the school’s administration that anyone caught participating in protests wouldn’t be able to graduate.

After leaving St. Augustine, Dawson spent a year living with family in Cocoa, before moving north to Philadelphia to work for an electrician. It’s an opportunity he believes would have been short-circuited had he continued to live in the South.

Conway, like Dawson, knew there was no economic opportunity for him the way things were. He was determined to play a part in making the country a better place for himself and future generations by any means necessary.

“We were in it to win it or die,” he says.

And they nearly did die at the hands of racist mobs. But speaking to the crowd assembled for the opening of Waves of Change, the men found an audience entranced by their stories.

When the event concluded, attendees — of various races, ages and backgrounds — thanked them for putting their lives on the line.

Preserving legacies

There are fewer and fewer people alive who share Dawson’s and Conway’s experiences, Laura Wynn, a social studies specialist for St. Johns County Schools, tells Jacksonville Today.

The fact that some St. Johns County students did not know that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested in St. Augustine during Freedom Summer was a reason Wynn believes it’s imperative students know and learn local history.

As primary sources are graying and dying, Wynn says students are losing that first-hand connection to the people who lived and in some cases endured what are now bedrocks of American history.

“It provides for engagement naturally,” Wynn says. “In the last few years, we have made a concerted effort to tell the big picture, state picture and local context. We have created local curriculum to do that.”

St. Johns County’s local history is richer than most.

Throughout the decades there have been extensive efforts to chronicle St. Augustine’s Spanish, British, Civil War and Catholic history. The 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer ignited local efforts to preserve and celebrate the city’s Black history.

Wednesday’s Waves of Change celebration is part of a series of events this summer to commemorate the 60th anniversary of Freedom Summer.

“History absolutely informs the present,” University of Arkansas African American history professor Candace Cunningham told Jacksonville Today in 2023.

“The context is different, but I think if you look over the long history of the United States, you do see these issues that have come up over and over again,” she said. “And yes, they are often around issues of labor, they are often around issues of economics, they are often around issues of social justice.”

Cunningham says the context around King’s most famous speech is an example. That event in August 1963 was officially called The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

In the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial, King challenged the United States to make real the promises of democracy and eradicate the indignity of Whites-only designations.

A year after that famous speech, King not only visited St. Augustine but rallied prominent people to support the local demonstrations through their presence or resources. Jackie Robinson came, as did Willie Gallimore, a Chicago Bears running back and Excelsior High graduate.

Six decades after Freedom Summer, Conway recalls there was something about the aura and love within King’s voice that drew people to listen and follow. He says listening to the civil rights icon in St. Paul A.M.E. Church in Lincolnville was an experience he will never forget.

Conway knew the potential consequences of his activism but demonstrated nevertheless because he believed the opportunity for economic freedom outweighed everything else. He says now that it was an informed decision.

As the principals of the Civil Rights Movement become ancestors — or like Dawson and Conway enjoy their retirement — Conway says it is vital that today’s young people are educated and informed.

“You can’t make concrete decisions if you don’t have the information,” Conway says. “To get the information, you have to know how to look for it and educate yourself.

“One thing the system did try to do, here in St. Augustine, was try to deny my generation education,” Conway continues. “Throughout my entire life, from the first grade to the 12th grade, I never received a new book in any subject. Everything was written in, the answers were put in some of the books. No! I never got one.”

Freedom Summer is not a textbook topic to Conway and Dawson. It’s their lived experience. The St. Johns Cultural Council aims to memorialize their experience, wading into the waters of the Atlantic, for generations to come.

The Waves of Change exhibit is now a permanent fixture at the St. Augustine Beach Hotel at 350 A1A Beach Blvd., right near the boardwalk leading down to the beach. Pedestrian access to the beach is open 24 hours a day, and the exhibit is available to view alongside the historic hotel.