Michael Wright remembers he was delivering mail when he found out his hometown would be home to a National Football League franchise.

Thursday night, the lifelong Jaxson sat inside the Legends Center to listen to the team’s proposal for how it could remain in town for the next 30 years, as the second of five community ‘huddles’ drew approximately 100 people to the Sherwood community center.

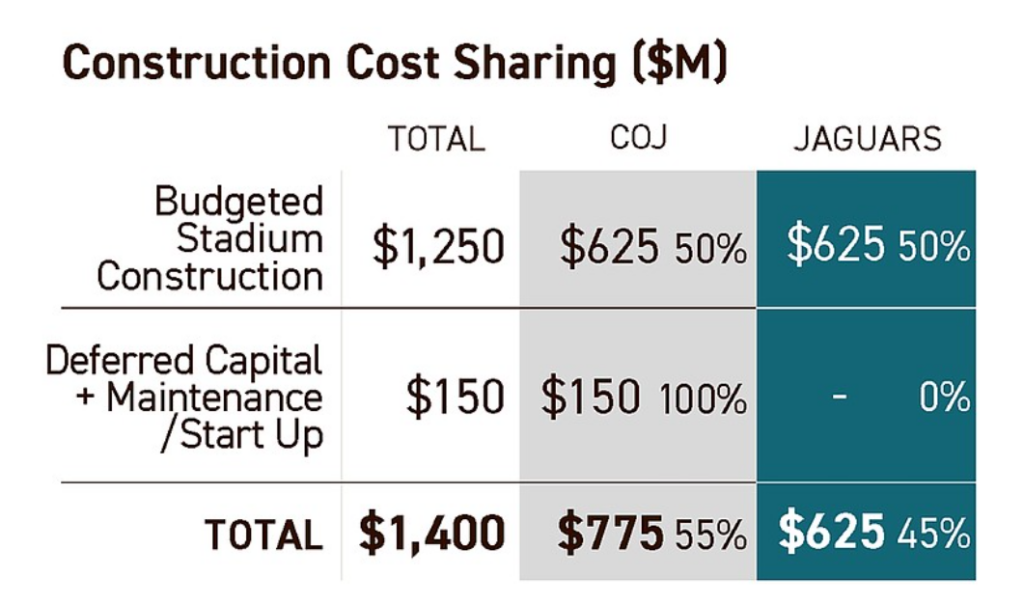

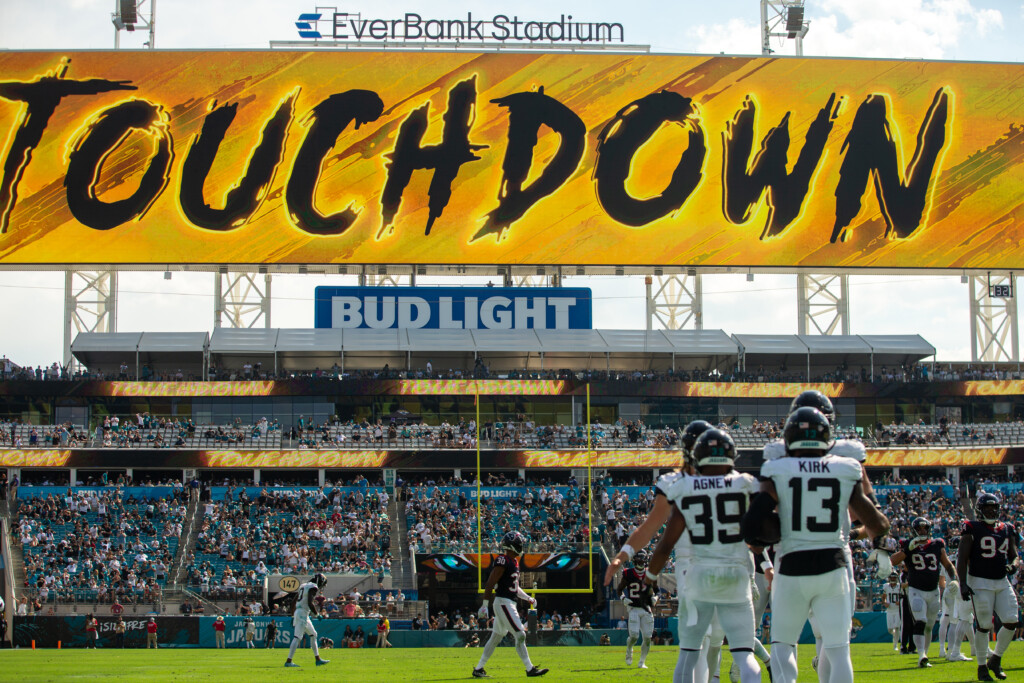

Jaguars team President Mark Lamping, Jacksonville Mayor Donna Deegan and the city’s chief negotiator, Mike Weinstein, spent an hour divulging their vision for renovations at EverBank Stadium. Both the Jaguars and the city would spend $625 million apiece on construction that would begin as early as February 2025 if the City Council and NFL owners accept it. The city would also spend an additional $150 million in deferred maintenance.

Wright sat through portions of the presentation with his arms crossed, but he left convinced.

“I think it’s a win-win. I’m with Mayor Deegan that you have to spend money to make money,” Wright said. “I go to other cities and I see how progressive they are. I want Jacksonville to be the same.”

Wright compared Jacksonville to Orlando and Tampa. Both Florida cities have invested millions in public facilities for sports teams in the last 15 years.

The Amway Center was erected on the edge of Downtown Orlando with more than $400 million in tourist tax dollars. Hillsborough County, the city of Tampa and the Tampa Sports Authority combined to pay nearly $30 million of a $160 million renovation of Raymond James Stadium.

On Thursday evening, Deegan stressed to the Legends Center crowd that ad valorem taxes will not be raised to fund the stadium renovations. Instead, a tax that was set to sunset would be extended.

‘No support for stadium’

Earlier in the day, the Northside Coalition activist group announced it was vowing to “oppose the billion dollars for a renovated football stadium and a billion dollars for a new jail unless another billion dollars is invested in Northwest Jacksonville and other neglected parts of the city.”

In a news release, Northside Coalition President Kelly Frazier said, “We appreciate City Council acknowledging the sins of the past against the Black community and the damage redlining had in Jacksonville, and now it is time for the city to put its money where its mouth is.”

The coalition didn’t mount an organized protest at the meeting, but as Deegan, Lamping and Weinstein took nine questions, they heard from Northwest Jacksonville residents who have lived there long enough to recall unfulfilled promises of previous politicians.

One resident asked why the city could devote so much care and attention to the stadium but not where it chose to build a morgue. Another challenged the team’s economic data that promises economic benefits for all of Jacksonville. Another asked why the stadium question could not be answered through a public referendum. Ultimately, several people pleaded for the city and Jaguars to honor promises being made in these community huddles.

Nearing the end zone?

Thursday also marked one year since Deegan’s upset victory. She pledged to listen to all of Jacksonville in the run-up to that win. Deegan began the day on the Eastside and ended it in Sherwood. In both communities, people were cautiously optimistic that the deal would benefit the Eastside, the historic, majority-Black community just to the north of the sports district.

Though the Jaguars are celebrating their 30th season this fall, the site where they play has been home to a football stadium for nearly a century.

In the 1920s, portions of the Eastside were razed to build what was then called Fairfield Stadium. That facility opened in 1928 as a place for the football programs from Lee, Landon and Andrew Jackson high schools. At that time end zones were on the east and west ends of the stadium.

Its capacity was doubled in the immediate aftermath of World War II to 16,000 seats and renamed the Gator Bowl.

The University of Florida and University of Georgia first played there in 1933. The rivals have played on that site every year since with the exception of 1994 and 1995 when the property was being renovated in preparation for the Jaguars.

It’s that history of development and displacement that gives Kacheryl “Cookie” Gantt pause. But she’s swayed by the proposed lease’s “community redevelopment agreement” that would see the NFL team and the city each set aside an additional $150 million over the course of the 30-year lease to focus on public parks, countywide initiatives like workforce development and affordable housing, specifically on the Eastside.

Lamping acknowledged on Tuesday at City Hall that there had been underinvestment in the Eastside for generations. He said the community redevelopment agreement would help erase decades of dismissal from the private and public sector.

“Some things are too good to be true. But, on the other hand, I think its still a good deal,” Gantt says. “It’s been a long time coming. I was there when the team came. …I’m on edge about eminent domain happening on the Eastside, A. Philip Randolph, because I’ve already been through that once.”

Gantt grew up Out East. She was a student at Matthew Gilbert Middle School when her family was displaced in 2001 as the city used Better Jacksonville Plan dollars to build what is now known as VyStar Veterans Memorial Arena.

Today, Gantt owns The Avenue Grill on A. Philip Randolph Boulevard, the Eastside’s main thoroughfare. She says she is excited that the proposal could allow for more local restaurants to become vendors inside the stadium.

“I think it’s a good investment for the residents of the Eastside,” Gantt says. “There are people out there who are 80 and 90 years old who have lived to see this moment.”