A three-judge federal panel unanimously upheld a controversial congressional map backed by Gov. Ron DeSantis, despite accusations he and the Legislature discriminated against Black voters.

The judges agreed that the plaintiffs failed to show the Legislature was discriminating when it approved Gov. DeSantis’ map.

“It is not enough for the plaintiffs to show that the governor was motivated in part by racial animus, which we will assume without deciding for purposes of our decision,” the court wrote. “Rather, they also must prove that the Florida Legislature itself acted with some discriminatory purpose when adopting and passing the enacted map. This they have not done.”

The lawsuit targeted DeSantis’ efforts to dismantle a congressional district in North Florida, a district that enabled Black voters to elect their preferred candidates for three decades.

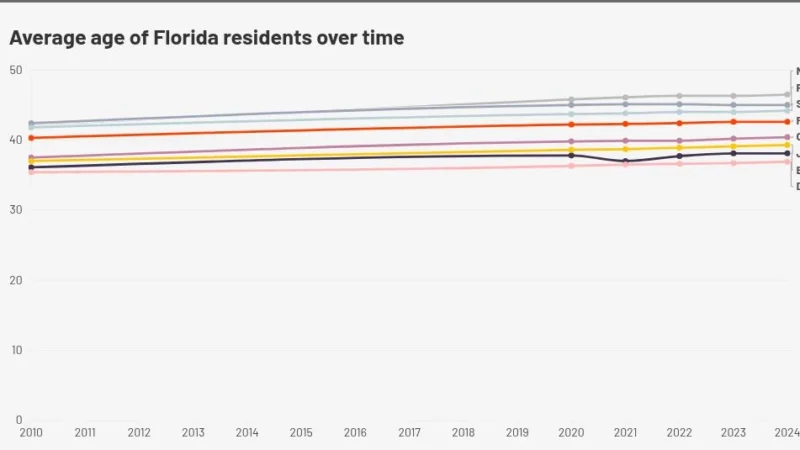

U.S. Rep. Corrine Brown, D-Jacksonville from 1993 to 2016, and U.S. Rep. Al Lawson, D-Tallahassee from 2017 to 2022, represented that district, which in its final iteration spanned from Jacksonville to Tallahassee. It was replaced by congressional districts that spread North Florida’s Black population across several districts, none of which elected Black voters’ preferred candidates.

The plaintiffs, which include a group of voters, Common Cause Florida, FairDistricts Now and the Florida State Conference of the NAACP, could appeal directly to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Common Cause Florida Executive Director Amy Keith said they were “currently in the process of analyzing the ruling and have not yet made a decision about next steps.”

On X (formerly Twitter), Florida Secretary of State Cord Byrd praised the ruling. “Boom!” he wrote. “Another huge win. More to follow.”

The governor’s communications director called the decision “ANOTHER Florida win.”

Yet the court’s decision doesn’t end the statewide dispute over the map. Another lawsuit awaits judgment from the Florida Supreme Court. Unlike the federal case, which scrutinized legislative intent, the state lawsuit questions the map’s direct impact on Black voting power, bypassing the need to establish discriminatory intent.

In a state trial, a judge ruled the map violated the Florida Constitution, but that decision was reversed on appeal. The state’s highest court will ultimately decide whether Florida is obligated to protect Black voting power in the future.

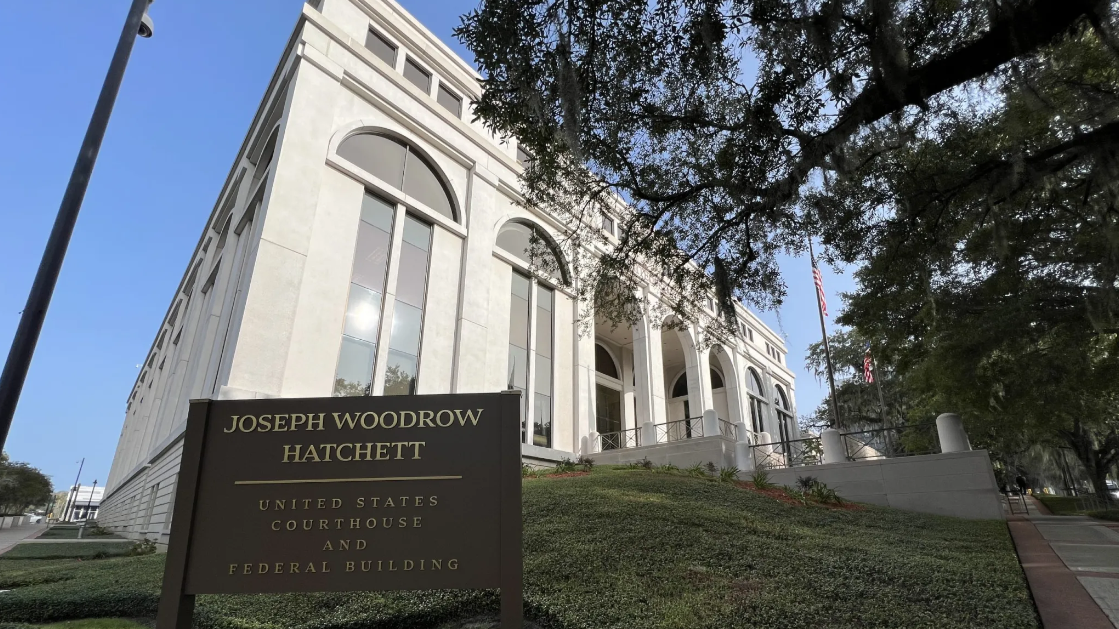

The three-judge federal panel, made up of U.S. District Judges M. Casey Rodgers and Allen C. Winsor along with 11th U.S. Circuit Judge Adalberto Jordan, pointed to the many efforts the Legislature took to preserve Black-performing congressional districts, even as DeSantis pressured the Legislature to fold, as evidence the Legislature did not discriminate.

“These are not the actions of a legislative body infected with racial animus,” the court wrote. “To the contrary, the Florida Legislature clearly fought hard and enacted congressional districting maps that it believed were compliant with the United States and Florida Constitutions, including the FDA’s non-diminishment provision.”

Eventually, the court said, “there did come a time when the Legislature seemed to run out of steam” and chose to enact DeSantis’ proposed map after a veto.

That wasn’t enough to prove racial discrimination, the court said. “Ratification of another’s racially discriminatory motives requires a conscious, deliberate choice by the decision-making body. This may be shown with evidence that the decision-makers themselves ‘agreed with’ the discriminatory motives. Or it may be demonstrated with evidence that the decision-makers knowingly chose a particular course of action for the purpose of giving effect to the discriminatory motives.”

While the state’s own expert witness agreed that “DeSantis’ veto was unique this cycle because it was a veto based on the racial composition of voters in the proposed district,” the plaintiffs needed to prove that the Legislature had discriminated against Black voters.

11th U.S. Circuit Judge Jordan and U.S. District Judge Winsor wrote separate competing opinions agreeing with the outcome of the case but disagreeing about DeSantis’ culpability.

Jordan wrote that DeSantis did intentionally discriminate against Black voters.

Winsor said that DeSantis didn’t. Instead, DeSantis was motivated by a desire to end race-based redistricting in order to comply with the state’s Fair Districts Amendments.

Winsor went so far as to suggest the state’s Fair Districts Amendments’ protections for racial minorities could be unconstitutional. The plaintiffs, he said, have not “shown that a state can use compliance with its own laws (here the Fair Districts Amendment) as a compelling state interest.”

The state lawsuit that is still pending doesn’t have to prove intent. Instead, it relies on the Fair Districts Amendments — voter-approved protections intended to prevent gerrymandering and uphold the voting strength of minority groups in Florida.

The state and the plaintiffs agree the new map reduced Black voting power, but they disagree about whether the “non-diminishment clause,” a legal protection that prohibits reducing minority groups’ voting strength, applies to North Florida’s Black voters.

A state trial court said it did and struck down the map, but an appeals court overruled that decision.

Ultimately, the Florida Supreme Court will decide whether DeSantis’ map remains in place or not, but that court has signaled whatever decision it makes is unlikely to come out in time for the 2024 elections.

This story is published through a partnership between Jacksonville Today and The Tributary.