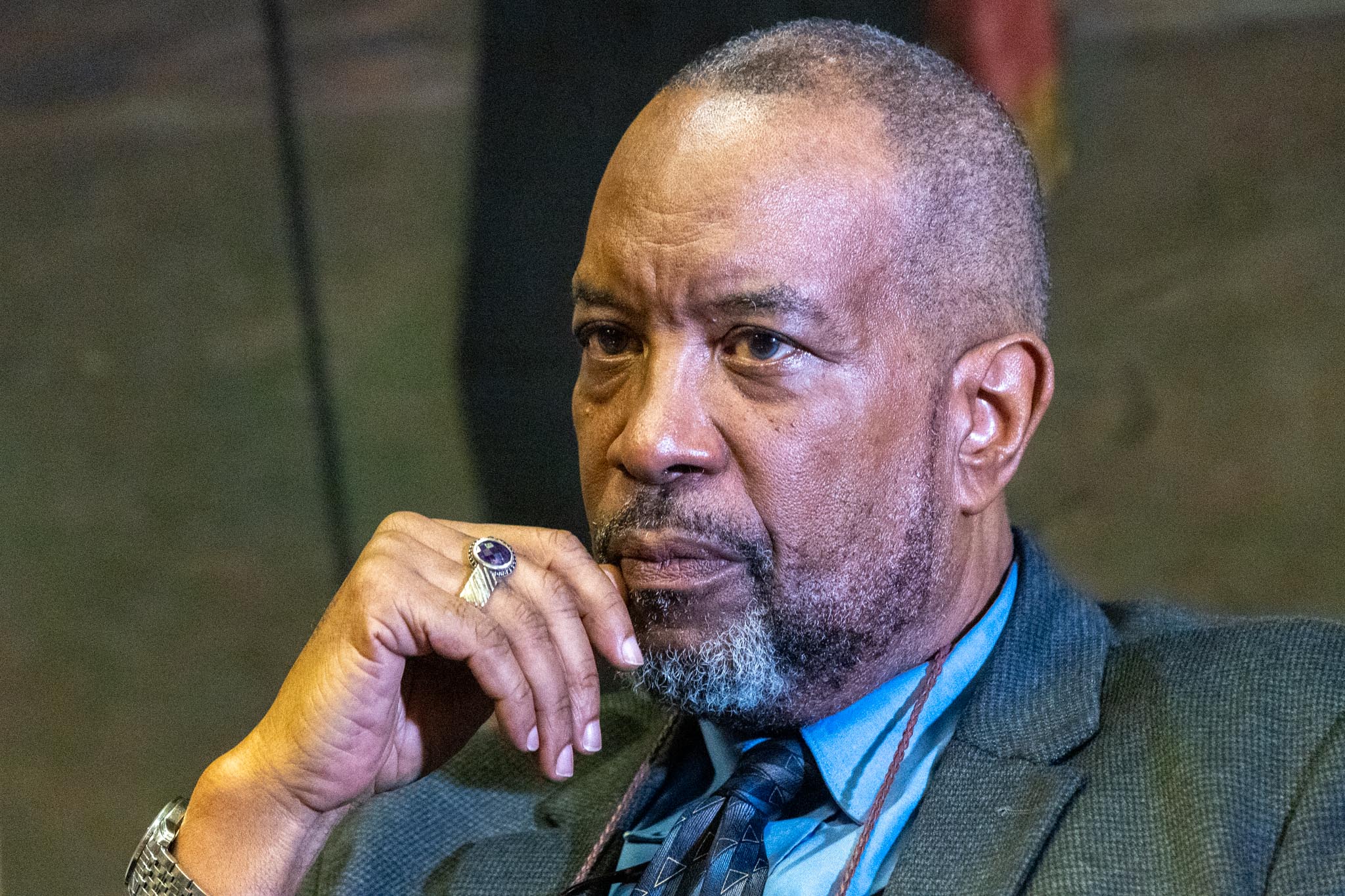

The presence of Donal Godfrey at Jacksonville’s City Hall on Friday was a reminder that the domestic terror that was commonplace during the American Civil Rights Movement is not ancient history. Godfrey, the survivor of a Ku Klux Klan bombing in Murray Hill, shared his story with current City Council President Ron Salem, who never heard about the bombing although he lived just blocks away at the time.

The Klan bombed the home Godfrey and his mom Iona King shared with family members in February 1964 in an attempt to stop school integration.

Their story is chronicled in the new documentary Just Another Bombing? It was screened at three Jacksonville theaters earlier this month. King and Godfrey returned to Jacksonville for the showings.

Tim Gilmore, a Florida State College at Jacksonville professor, covered the the bombing in his Jax Psycho Geo blog in 2017. That’s how Georgia filmmaker Hal Jacobs learned about the story and connected with Godfrey and King.

Godfrey’s public education began nine years after “separate but equal schools” had been outlawed in America. But Jacksonville, like many Southern cities, was not in a rush to integrate schools.

His mom, King, had moved to Jacksonville as a child in the 1940s. Her aunt, Isabel Boundrent, was sick at the time and family members came from across the Southeast to tend to her. King graduated from a segregated Stanton High School in January 1957 and worked as a housekeeper.

When it came time for her son to go to elementary school, King looked no farther than the neighborhood school near their home: Lackawanna Elementary on Lenox Avenue.

“People keep telling me how brave I was,” King says. “I wasn’t being brave. I was just being a person who felt that I had a right to put my child where my child needed to go. He needs to go to school. He needed to go to the school that was closest to us.”

At the time, the school was all-white. Godfrey, now 66, was one of the first students to integrate a public school in Duval County.

“We walked right past people that were waiting for the bus to come,” Godfrey remembers. “And, as we walked to Lackawanna, white women with their children asked her, ‘Where do you think you’re going with this little nigger? You’re not going to our school.’ We were berated and cursed all the way there.”

In the early hours of Feb. 16, 1964, when he was 6 years old, the Ku Klux Klan placed stolen dynamite under his home. It exploded underneath the living room that Sunday morning. His mom recalls that she’d stayed up late the night before preparing a cake.

“It blew…”Godfrey began.

“Crevices,” King interjected.

“Crevice is a good word,” Godfrey continued, “from the front door all the way to the living room. …To get out (of our house), we had to walk around the edges to get to the front door.”

The explosive was placed on the right side of the home. Because the family were asleep on the left side of the house, they all survived.

“The police didn’t come,” King recalled. “The fire station didn’t come. No one came.”

Godfrey says he has no idea how the FBI started to investigate the bombing.

At the time, Jacksonville’s daily newspaper covered the bombing but the story didn’t make the front page. Local Black newspapers, as well as the Atlanta Daily World, also covered the incident. It was also picked up by wire services and reported in The New York Times.

The scant local coverage may be why City Council President Ron Salem, who grew up in Murray Hill blocks away from Godfrey, did not know about the bombing until this month.

Godfrey and Salem swapped childhood stories on Friday. Unbeknownst to each other, they attended what was then known as Robert E. Lee High School in the early 1970s. Salem graduated in 1973, Godfrey in 1975.

At the time of the bombing, Salem was a student at nearby Ruth N. Upson Elementary who remembers the 1963-64 academic year vividly because President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in November.

“It’s only 60 years ago that we were bombing families out of their homes. I mean, that’s in my lifetime. It’s a little shocking,” Salem said.

The bombing came five months before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed. Section IV of that landmark legislation mandated “the assignment of students to public schools and within such schools without regard to their race, color, religion or national origin.”

After a 45-minute conversation, Godfrey signed his 2019 autobiography, Leaving Freedom to Find Peace, for Salem.

“Writing the book was therapeutical for me,” Godfrey says. “It made me drill down and deal with some of the things that I suppressed. In the writing, the book I cried, I cried. There are certain parts of the book right now I still tear up.”

The City Council president, a self-described football fan, said it blew his mind that Godfrey and King lived with Pro Football Hall of Famer Harold Carmichael’s family in Moncrief for a spell after the bombing. (Carmichael is a Raines High graduate.)

Godfrey finished first grade at Susie Tolbert Elementary in Grand Park. He then attended Forest Park Elementary for three years before returning to Lackawanna in fifth grade “after integration was enforced.”

“That was, like,1969 when it was forced,” Salem recalled.

In October 1969, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that “School districts must immediately terminate dual school systems based on race and operate only unitary school systems.”

City Council member Tyrona Clark-Murray also attended the meeting on Friday. When she mentioned that she is on the faculty at Dupont Middle School — the same school Godfrey once attended — King’s face lit up and she challenged Clark-Murray to use her position as an educator and elected official to speak up and keep pushing forward toward inclusion.

To this day, Godfrey and King are still cautious while visiting Jacksonville and careful not to broadcast their location to the masses. While many things have changed here in the last 60 years, Jacksonville has also seen a series of public displays by white supremacists over the last 18 months, from public testimony at government meetings to the targeting and killing of three Black people at a Dollar General in Grand Park last August.

Today, Godfrey lives in a village outside Accra, Ghana. He moved to the West African country after a decades-long career in the military and United States Foreign Service exposed him to people and cultures beyond Murray Hill.

As for what has changed in their former hometown, King notes the two interstates, specifically I-10, have cleaved Black neighborhoods. Railroad tracks and an arterial road, Roosevelt Boulevard, separate Gilmore Street into three chunks. The home where Godfrey and King survived the bombing is a short walk away from the North Riverside community that’s trying to resist gentrification.

“I am sure that it is a planned situation to run the interstate through communities. And, they seem to be communities of color, that displace people,” King said. “Nationwide, there is a horrendous need for affordable homes. And, when these people are displaced, where do they go? What do they do? …Can you afford to move after you’ve (been displaced?). They’ll give you a couple dollars, yes. But, it isn’t enough to sustain your new lifestyle that they have made you create.”

King says it’s vital that stories like hers are told for generations to come.

“You need to talk to your elders, get their history,” King says. “Like with this, I wasn’t willing to go back and deal with that. Who wants to dig up death? Because had we not survived (the bombing), we would have been dead.”