Barnett’s Subdivision is a small neighborhood within the larger Durkeeville community that has a very rich history. In honor of National Black History Month, here are five facts about Barnett’s Subdivision that most Jaxsons may not know.

Historical background

On July 1, 1902, the Jacksonville City Council granted a streetcar franchise to the North Jacksonville Street Railway, Town, and Improvement Company. This new streetcar line serving what would eventually become known as the neighborhoods of Northwest Jacksonville generated national attention because it was a predominately Black-owned and operated company during the early years of Jim Crow-era segregation.

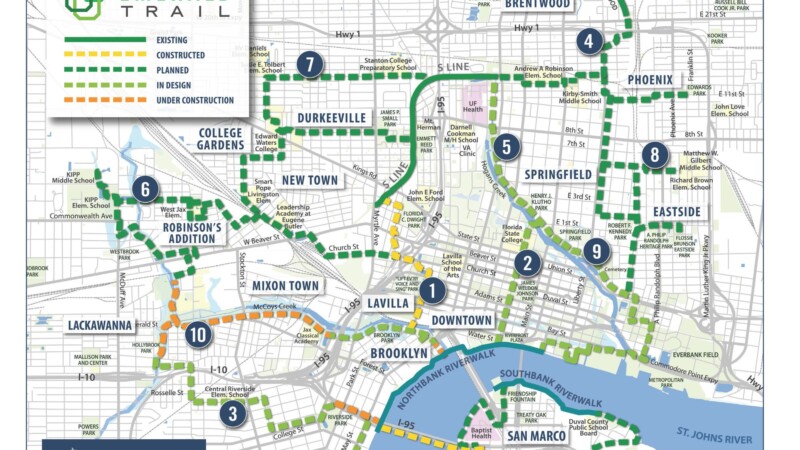

Served by the streetcar line, Barnett’s Subdivision became an attractive and vibrant neighborhood for many middle-class African American families following the Great Fire of 1901. Platted between 1907 and 1908 a few miles northwest of Downtown Jacksonville, Barnett’s Subdivision was a development roughly bounded by Kings Road north to West Fourth Street on the east side of Myrtle Avenue and West Seventh Street on the west side of Myrtle Avenue, and from the S-Line Urban Greenway west to Whitner Street, near the campus of Edward Waters University.

Today, Barnett’s Subdivision is generally accepted as being a part of the greater Durkeeville neighborhood, which is located north of Kings Road and west of Interstate 95. Here are five interesting historical stories and facts associated with the subdivision’s past.

1. Named after the founder of Barnett National Bank

Barnett’s Subdivision is named in honor of William Boyd Barnett, who owned the land in the 19th century. Born in Nicholas County, West Virginia, Barnett sold his interest in a Kansas bank and relocated to Jacksonville in 1877.

With a capital investment of $43,000 and a staff consisting of him, his son Bion as the bookkeeper, and one other clerk, he founded a new local bank in 1877. In 1901, his bank was the only one in town that survived the Great Fire that consumed most of the city. By 1995, Barnett Bank had grown to become Florida’s largest bank and a Fortune 500 company with revenue of $3.10 billion. At its height, it employed nearly 19,000 workers in Florida and Georgia and was the 20th largest banking organization nationwide with more than 600 offices statewide. For many years, the bank was Jacksonville’s leading corporate giver.

In 1997, Nations Bank announced its plans to acquire Barnett. At the time, it was the largest banking merger in American history.

2. Home to one of Jacksonville’s last surviving Green Book sites

First published in 1936, the Negro Motorist Green Book was a compilation of restaurants, overnight accommodations, gas stations and other public services for people of color traversing a “white-only” landscape for Black travelers during segregation. Jacksonville was a major Florida destination featured in the document.

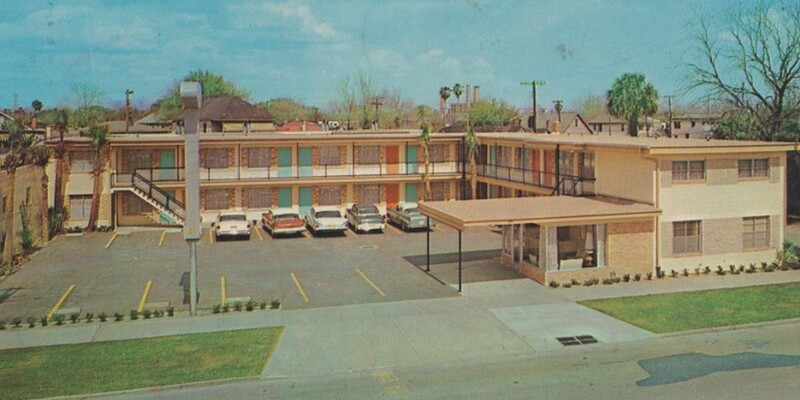

Located at 1251 Kings Road, Barnett’s Subdivision’s former Fiesta Motel is Jacksonville’s last surviving Green Book site that was not located in the nearby LaVilla neighborhood. The Fiesta Motel was a motel for Black travelers when it opened in 1961 with 26 air conditioned rooms, each with television and telephone. The old motel is now the 1251 Efficiency Apartments.

3. Architectural works of Joseph Haygood Blodgett

Barnett’s Subdivision may be home to the largest collection of surviving structures designed and built by noted African American architect Joseph Haygood Blodgett. Blodgett’s life and works are a quintessential example of a local rags-to-riches story.

Born into slavery in Augusta, Georgia, Blodgett moved to Jacksonville during the 1890s with one paper dollar and one thin dime to his name, initially working for the railroad for a dollar a day. In 1898, he became a building contractor.

The Great Fire changed the fortunes of Blodgett in 1901. During the rebuilding effort, Blodgett not only designed and built 258 houses but he kept 199 to rent, which eventually made him one of the city’s first Black millionaires. Philadelphia merchant John Wannamaker was astonished that a Black man could accumulate such a fortune in the South without capital and a formal education.

Blodgett’s design trademark was the inclusion of a small upper porch above a large lower porch that often extended around the side of a house. While the majority of Blodgett’s work has been lost through years of local urban renewal programs, a large number of Blodgett-designed residences remain in Barnett’s Subdivision.

4. Zara Cully-Brown Lived Here

Miller’s Grocery is a two-story brick building that was erected in 1929 at 1481-1485 North Myrtle Avenue. Owned and operated for 45 years by Cornelius Nathaniel and Mary Gibson Miller, the store was a popular neighborhood destination known for its giant “slaw dogs” and having the best fresh liver in town. In addition, a second retail storefront in the building was a popular speakeasy that was operated by Billie Ruth McCoy. Famous guests included musicians James Brown and Jackie Wilson and Jacksonville Braves baseball player Hank Aaron.

Famed actress Zara Cully-Brown was a tenant in one of the second floor apartment units. Born in Worcester, Massachusetts, Zara Cully married Jacksonville-born James McCoil Brown in 1914. Soon, the couple relocated to Jacksonville, where Zara worked as a drama and elocution teacher at her own studio and at Edward Waters University for 15 years.

While living in Jacksonville, Cully-Brown became known as Florida’s “Dean of Drama.” In the early 1950s, the family relocated to Hollywood, California, after growing tired of experiencing racism in Jacksonville. At the age of 82, she originated the Mother Jefferson role on the CBS sitcom The Jeffersons. Easily the funniest person on the show, at the time of her death in 1978, she was one of the oldest active performers on television.

5. A link to John D. Rockefeller

In 1886, the Jacksonville Belt Railroad was constructed to serve as a rail bypass around Downtown by connecting rail lines in Jacksonville’s Eastside with rail lines in LaVilla. Forming the east boundary of the Barnett’s Subdivision development, the belt railroad was eventually acquired by the Seaboard Airline Railroad. Abandoned during the 1980s, the former railroad is a shared-use trail called the S-Line Urban Greenway. The S-Line is what the Seaboard Airline Railroad had been called, while the company’s main competitor, the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, was known as the A-Line.

When this railroad through Barnett’s Subdivision was operational, it attracted many industries requiring freight rail service along its path. One of these, among the largest warehouses built in Barnett’s Subdivision, was constructed shortly after the Great Fire of 1901 for John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Co.

The Standard Oil Co. was incorporated in 1870 by Rockefeller and Henry Flagler. At its height, it was the largest petroleum company in the world. The company’s success made Rockefeller one of the richest people in modern history. The company was so successful that the business came to an end when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that it was an illegal monopoly in 1911. Flagler, Rockefeller’s Standard Oil business partner, took advantage of his wealth to build LaVilla’s Jacksonville Terminal passenger rail station, now the Prime Osborn Convention Center, and the Florida East Coast Railway between Jacksonville and South Florida.

The former Standard Oil Co. plant in Barnett’s Subdivision still serves a similar purpose more than a century later. Today, it is the location of the H.R. Lewis Petroleum Co.