My son was called a ni**** by a classmate at school. It’s happened twice that I know of, once on the bus and once in school. I knew it would happen at some point. Living where we do, he attends a school where you can count the number of Black students in his class on one hand. I asked him what led up to him being called that name. He and the student aren’t friends. They were arguing with each other. My son used choice words. So did the other child. And yet the impact of one certain choice word is not the same as all the others.

I asked my son if he knew what the word meant.

“It means monkey,” he said.

I told him that was incorrect. I told him that the word was what white people used to make Black people feel bad about themselves. I asked him if he had learned about slavery. He said no. He’s in third grade. This is his first year with a social studies curriculum, class and grade.

I told him about how African people were kidnapped, chained, and enslaved. I told him that when the white owners referred to the enslaved people they used that word. I told him no matter how many times he hears it used colloquially, when he’s called that name by a white person it is meant to insult and hurt.

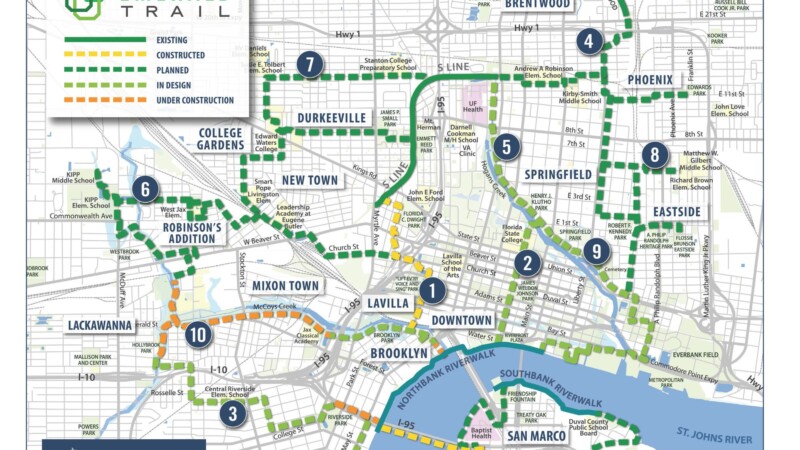

I told him we would have to take a trip to Kingsley Plantation so he can see the remains of the history of slavery and the conditions Black people worked under without being paid for their labor. I know the story of Kingsley Plantation and its Black woman owner is much deeper than the simplification I gave my son, but it is a beginning.

Having to explain this history made me think back on a time when I was forced to reckon with the history and power of the word. I was 16. I had read the book 47th Street Black and in it one of the characters was repeatedly called “an uppity ni****.” A phrase I wrote in an essay for school as I was giving a summary of the story. My mother read over my report before I turned it in and then said to me, “You can’t say that.”

“Why,” I asked.

“It’s a bad word about Black people from slavery.”

I revised my book report to remove the offending word, still unaware of its true harm as I’m sure my son is unaware right now. Like him, I had heard the word colloquially. From family members, in music, on TV. The word is ubiquitous in the Black community. As the claim goes, we’ve reappropriated the meaning into one of endearment amongst ourselves. And yet it still hits different when you hear it directed at you as insult, as menace, as threat, as a reminder to know your place.

I was 19 the first time the word was yelled at me, a story I’ve recounted in this publication before. I was angry then. Now that it has happened to my son, so much earlier than when it first happened to me, I am only sad.

I am sad that he too will grow up in a world where he is reduced to the color of his skin and assumptions are made about who he is, what he believes in, and what he stands for based on that one phenotypic expression of his humanity. I am sad that I will have to supplement his education with field trips, books, and other cultural experiences to bolster his understanding of his ancestry, his heritage, and his culture and why some people in the world will hate him for it. I am sad that I will have to teach him how to recognize and identify prejudice, discrimination, racism, and white supremacy so that he has a reference point for history and the history that we see repeat itself in the present.

The weight of one word, with its centuries of history embedded in the enunciation, has brought all of the “anti-woke” policies of the DeSantis administration into my home and set them on my kitchen table to untangle for my children so that they may understand the difference between history and political propaganda.

Words matter. Words can hurt. And sometimes, most times, they’re intended to.

Nikesha Elise Williams is an Emmy-winning TV producer, award-winning novelist (Beyond Bourbon Street and Four Women) and the host/producer of the Black & Published podcast. Her bylines include The Washington Post, ESSENCE, and Vox. She lives in Jacksonville with her family.