One Saturday a month, at an apiary at a community garden in West Jacksonville, about a dozen beekeepers talk among themselves and compare bee notes.

They speak their own language: “The queen has already gone in and filled out 10 frames on that super … with capped brood … I mean she just went in there and went ape crazy.”

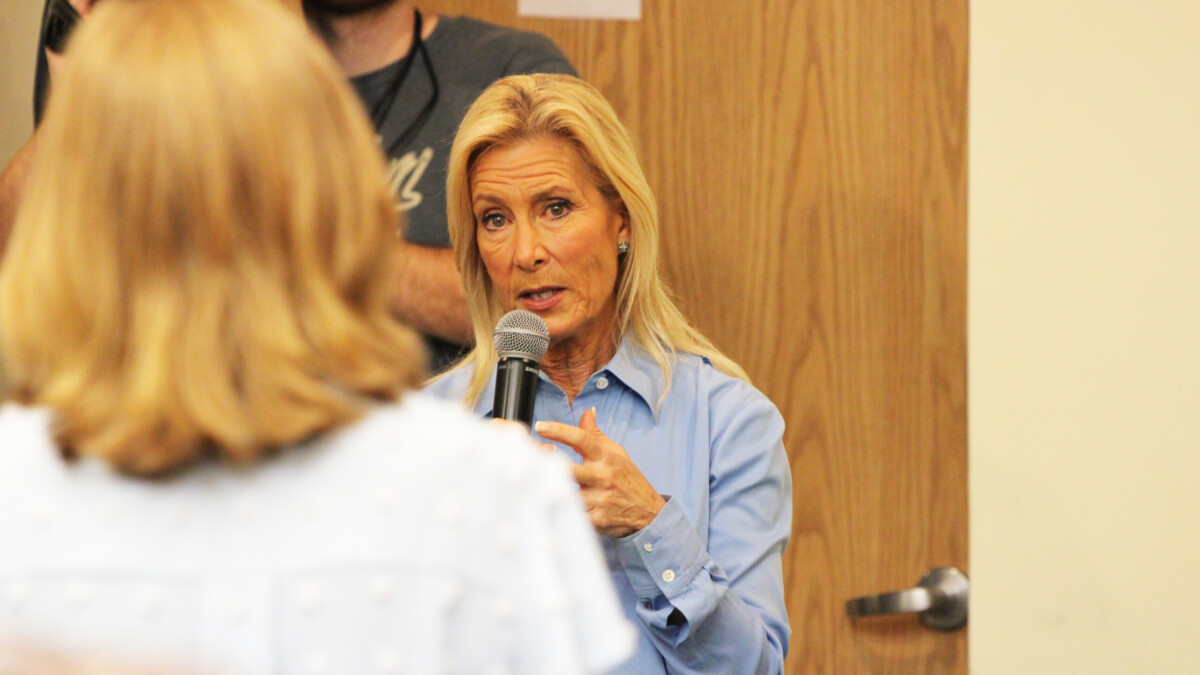

One of those beekeepers is Carol McBryde of Jacksonville, who started tending to bees more than 40 years ago as a hobby. She has about eight hives in her big backyard and a few customers she provides honey to.

McBryde says today’s burning question is “Where’d all the honey go?” The honey flow in the spring was a lot less than it has been in the past.

Bees today are threatened by parasites, pesticides and climate change. The nearly 3 million bee colonies in the U.S. is less than half what it was in the mid 20th century, and it has remained flat since the early 2000s.

“And most of us long-term beekeepers got little or no honey this year,” McBryde said. “So it’s probably environmental. I think the rain just washed the nectar and pollen off the plants, is why we didn’t get the honey flow that we normally get during that season.”

Helping to answer questions like that is mentor Michael Leach, who with his wife, Christie, owns Bee Friends Farm in Jacksonville.

In 2009, Leach started building beehives for other keepers. And he is heavily involved with the Jacksonville Beekeepers Association. Club members can ask him questions about their apiaries and why their bees are acting agitated or defensive.

“So some of the newer members that may be first year behivers will be experiencing more aggressive bees, and they’re gonna be wondering why, because of the fear of Africanized or killer bees in Florida. And so it kind of gives that alarm that maybe I do have a problem,” Leach said.

They also might talk about disease and pests. “Twenty percent of those mites are attached to the adult bee. … They’re in the comb on the cappings” — like the parasitic Varroa mite, which latches onto adult and adolescent bees returning to their colonies, and then mites’ offspring feast on bee blood.

“We want to know how high the threshold is of those mites,” Leach said. “So we’ll test for that and then if the threshold is reaching certain limits, we’ll apply treatments to the hive that will help mitigate that a little bit.”

The Jacksonville Honeybee Festival will be 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Saturday at the Jacksonville Fairgrounds.