With school starting as soon as this week in parts of Northeast Florida, the state’s African American History Task Force is trying to get teachers up to speed on new social studies standards.

Those standards have sparked national outrage over their framing of slavery, and a new prominent voice just joined the chorus.

Nikole Hannah-Jones, founder of the New York Times’ 1619 Project, criticized the standards in a discussion last week. Her project won the Pulitzer Prize for its portrayal of slavery, but it is banned from Florida classrooms under a law signed in April 2022 that restricts race-related instruction.

Hannah-Jones says most states do not do a good job of teaching slavery’s foundational role in creating America. With the standards as written in Florida, she says, students are missing context.

“When students in Florida look at the living conditions of Black people in the state versus white people, versus Latinos, based on what race those Latinos are, the history that they’re being taught does not explain what they are seeing. So, they are getting a very whitewashed version of history,” Hannah-Jones says.

Florida’s African American history standards have been criticized over two main points — for suggesting that slaves learned skills that benefited them and for a description of anti-Black massacres as “acts of violence perpetrated against and by African Americans.”

Vice President Kamala Harris labeled the standards “propaganda” in a visit to Jacksonville last month.

Hannah-Jones says the new standards may be accurate individually but they cherry-pick facts and paint an incomplete full picture of American slavery.

“They’re getting a history that really tries to oversimplify what was a foundational American institution,” Hannah-Jones says. “(It’s) one that I think then puts them out into the world very ill-equipped.”

Hannah-Jones’ 1619 Project was launched in 2019 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of African slaves being brought to the Americas. It sought to contextualize the role chattel slavery played in the establishment of the United States and its role in the American political, social and economic systems.

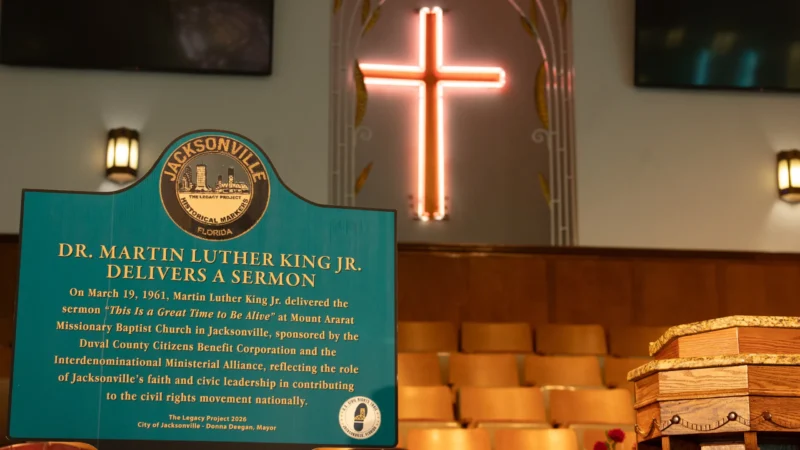

The Florida Board of Education banned the 1619 Project from being taught in schools during a meeting held in 2021 in Jacksonville, saying it was an example of distorting history and indoctrinating students.

At the time, board member Tom Grady called the 1619 Project “opinion and narrative disguising as fact, promoted by others with a different agenda, intended to divide us into racial buckets.”

The 1619 Project also fell under the Individual Freedoms Act signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis in April 2022 — a law he branded the “Stop Wrongs Against Our Kids and Employees Act,” or Stop WOKE Act.

Under that law, various race-related concepts would constitute discrimination if taught in classrooms or while training employees. Specifically, it prohibits instruction that leads people to believe they are responsible for adverse acts committed in the past by people of their same race or sex.

Hannah-Jones was among the panelists during a discussion on Black history at last week’s National Association of Black Journalists’ Conference and Convention in Birmingham, Alabama.

Others included Emory University political science professor Andra Gillespie as well as University of Alabama at Birmingham professor Tondra Loder-Jackson, whose research has focused on urban education and teacher preparation.

Loder-Jackson noted that in previous generations, Black history was taught in households, either through books or oral histories.

It’s a refrain that disparate groups in Jacksonville have picked up as they have sought to teach what they deem is a more complete version of the history of American slavery and its ramifications through churches or through community groups.

Concerned parents at one Northwest Jacksonville elementary school are working to create a Freedom School. Elsewhere, community groups are holding weekly meetings to devise how it can work to repeal the Individual Freedoms Act that led to Hannah-Jones’ work being banned and the creation of the new social studies standards.

Florida Commissioner of Education Manny Diaz Jr. says having African American history standards that are a standalone portion of the social studies standards “will bring African American history to life for our students.”

Fernandina Beach native William Allen served on the 13-person work group that created Florida’s Black history standards. He defended their work Monday during a teacher training session.

Allen says the story of African American history is one of advancement that has come “steadily if not glacially and, perhaps, not yet reached the climax of its plotline.” He professes that the story of African Americans is not parochial to Black people.

He says the workgroup wanted to incorporate anecdotes of people into the standards to help students understand the information taught to them.

“This curriculum is comprehensive in scope; it is not exhaustive in detail,” Allen says. “Nothing could be exhaustive in detail. … We are comprehensive, but we’re also attentive to what can actually be processed. And, that’s why we focused on stories so much as we did, because those can be processed. Students can immediately understand the story and they can therefore develop the critical apparatus for being able to interpret them.”