Many books and articles on local history feature the Timucua town of Ossachite, said to be the native precursor to Downtown Jacksonville. There’s just one problem: Ossachite never existed. This is the story of how the story spread, a new theory on where it came from, and how it became embedded in Jacksonville mythology.

An inactive interim in local history

The first person to write about Ossachite was historian T. Frederick Davis, whose 1925 book The History of Jacksonville, Florida and Vicinity was the first comprehensive academic history of the First Coast region. Chapter II begins with a survey of Florida’s first Spanish period, 1565-1763, which Davis calls “a sort of inactive interim in local history,” the type of dark age that makes a fertile field for myths and legends.

The area that would become Jacksonville wasn’t nearly as inactive as Davis thought — more on that in a bit — but it’s true that the future site of Downtown Jacksonville saw little habitation until the British established a ferry crossing there in the 1760s. Even so, Davis notes that the area saw periodic visits and use by the Spanish, British and Native Americans. On page 24, he mentions an especially interesting item:

“At the foot of Liberty Street there was a rather bold spring of clear, good water (an outcropping, perhaps, of the stream that is known at the present day to underlie the surface in that section of the city). Back from the river a short distance stood a small Indian village.”

In a footnote to this passage, Davis adds:

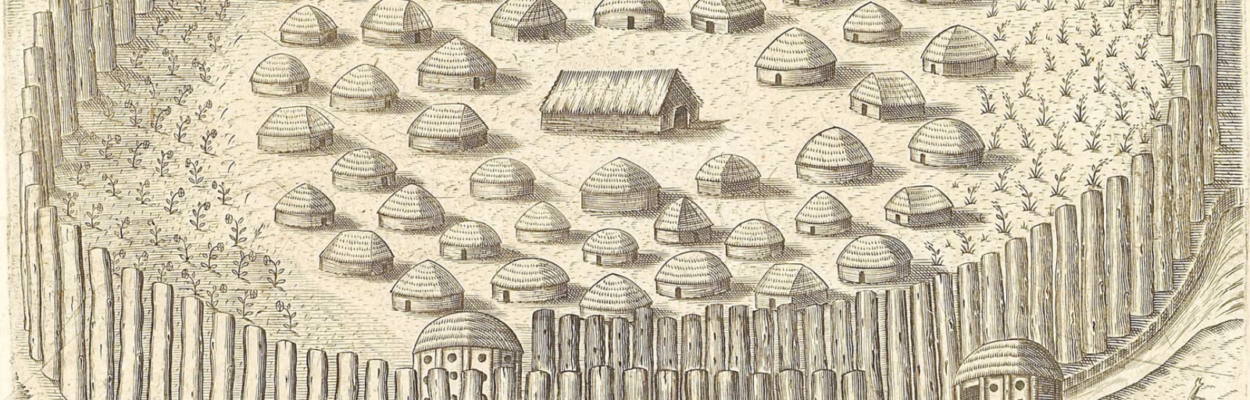

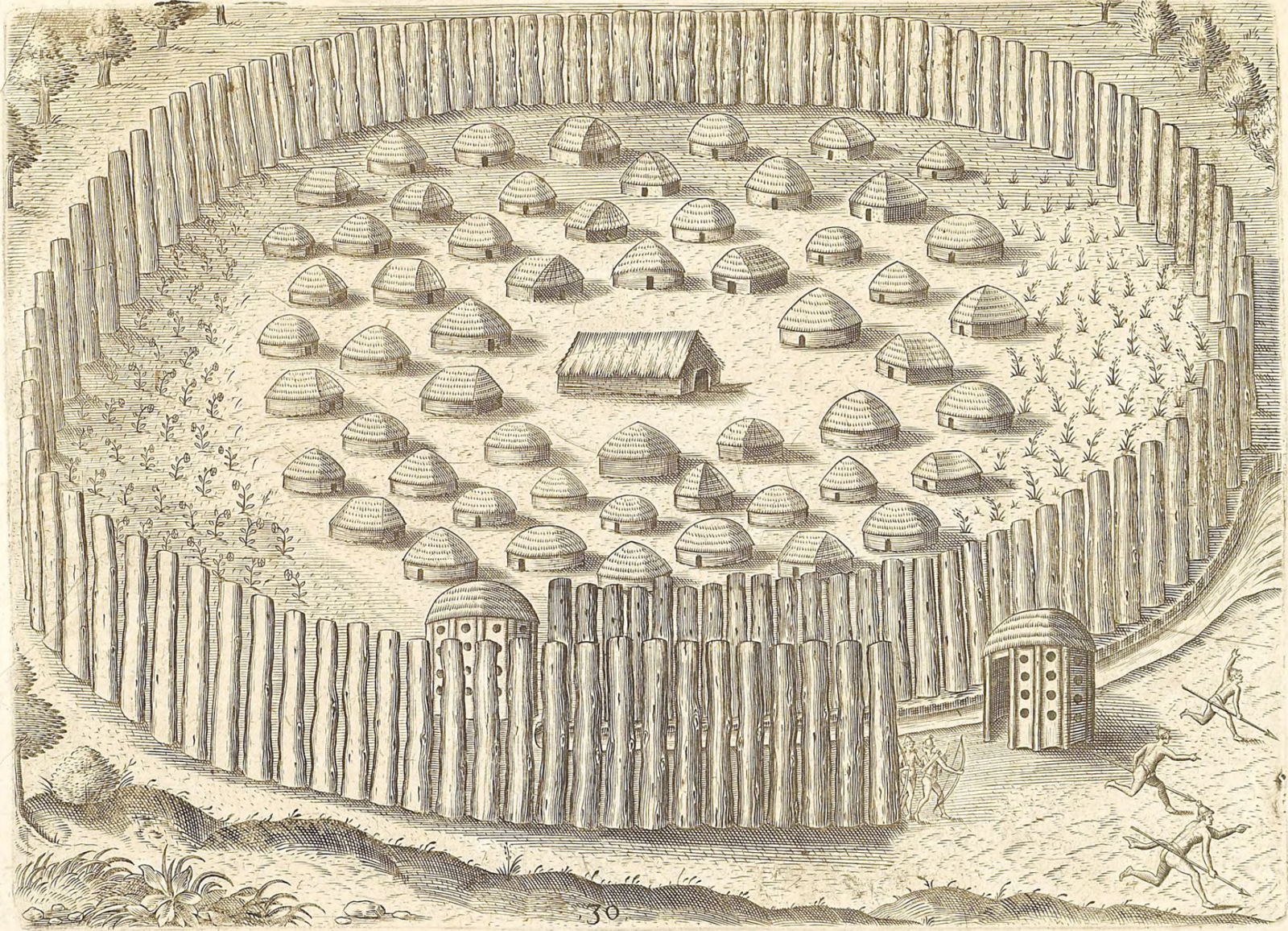

“One of the earliest Spanish maps shows an Indian village here called Ossachite. This liquid Indian name, Os-sa-chi-te is the earliest record of a name applying to the locality of Jacksonville. It was a Timuqua village of probably not more than half a dozen houses thatched in the Timuqua style, as shown by Le Moyne’s drawings.”

Davis’s evocative passages about Jacksonville’s supposed Native American precursor have long captivated Jaxsons eager to know more about the city’s rich but often neglected past. Unsurprisingly, many a book and article on local history have included Ossachite, frequently along with Davis’s claim that this was the first known name for the Downtown Jacksonville area.

Ossachite spreads

Davis’s reference to Ossachite quickly caught the eye of the Jacksonville Historical Society, which was founded in 1929. In 1931, JHS received funding from City Council to erect a series of markers at the sites of important historical places and events. Along with markers for the Cow Ford, the Union picket lines from the Civil War and others, JHS placed a plaque for Ossachite at the northwest corner of Julia and Monroe streets.

Though easily missed among the landscaping today, the sign reads: “Site of the ancient Timuquan Indian town of Ossachite from earliest times until about 1700.” It’s not clear from the JHS annual why they chose that specific site, then the location of the main post office (now the Ed Austin State Attorney’s Office), but ever since, it has testified to generations of pedestrians about the supposed lost town.

Generally citing Davis, Ossachite is referenced as the native forerunner to Jacksonville in popular works like Edna and Lula Krause’s From Pines to Skyscrapers (1955), Bill Foley and Wayne Wood’s The Great Fire of 1901 (2001) and Donald J. Mabry’s World’s Finest Beach: A Brief History of the Jacksonville Beaches (2010). Earlier editions to Wayne Wood’s landmark Jacksonville’s Architectural Heritage include it too, but the 2022 edition notes that recent researchers have doubted its existence. More skeptical takes on Ossachite have more recently appeared in Tim Gilmore’s site Jax Psycho Geo and my book Secret Jacksonville.

One of the most popular versions of the Ossachite legend was written in 2003 by Glenn Emery, creator of the erstwhile website JacksonvilleStory.com. Emery was a librarian for the Jacksonville Public Library with master’s degrees in library science and history. His website chronicled some of the forgotten aspects of Jacksonville’s history, and his writings were so admired that after his death in 2006, they were integrated into the website of the Jacksonville Historical Society.

Calling Ossachite the “grand Timucua city,” Emery wrote that it “proved bigger than other communities in the area” and that it “thrived 1,000 years ago, but it survived until about 300 years ago.” Emery suggests it may have been centered at the old Courthouse site on Liberty Street. He wrote that Ossachite had a mound and massive council house, and was home to “potters, painters, wood carvers, shell workers, and copper artisans.” When the Historical Society moved the page to its website, additional details were added calling Ossachite “the Timucua metropolis in Jacksonville’s past” and saying its population “at one time numbered over 2,500 people.”

Historical evidence

Accounts like these are intriguing, but there’s a problem: There’s no evidence that Ossachite ever existed. Since the late 20th century, we’ve seen an explosion in research about the Timucua people, their language, and native and European sources documenting their lives. Historical sources for the Timucua include French, Spanish and English texts as well as letters and books written in Timucua.

These sources mention dozens of Timucua towns and settlements; known Mocama Timucua towns in the Jacksonville area include Saturiwa, Moloa, Alicamani and Athore. In the late 16th century, the Mocama became part of the Spanish mission system, and a sizable mission, San Juan del Puerto, was established at one of their main towns on Fort George Island. While dozens of towns across the Jacksonville area appear in native and European records from across several centuries, none mention Ossachite, or any settlement in Downtown Jacksonville.

Archaeology is similarly silent; there’s no evidence for a large native settlement or mound in Downtown Jacksonville. The Mocama lived around the St. Johns River mouth and surrounding islands and inlets, but the area of Downtown had little if any settlement — in fact, the whole area between Downtown and roughly Palatka may have been an unoccupied buffer zone between the Mocama and another Timucua chiefdom, the Utina, with whom they were often at war.

If a city named Ossachite once occupied Downtown Jacksonville, it vanished without leaving a single trace of its existence.

But where did it come from? Fortunately, the ongoing research on the Timucua leads to a theory — one that involves a guy misreading a map 100 years ago.

A legendary error?

My friend Doug Henning, a Timucua language researcher working on the Timucua database project, believes that the name may be a corruption of Uzachile, a Timucua town in the Florida Panhandle west of the Suwannee River. Uzachile, also written Ossachile, was the capital of the Yustaga chiefdom at the time of the Hernando De Soto expedition in 1528. Having heard of De Soto’s brutality, the citizens of Uzachile abandoned the town before the Spanish arrived. Uzachile is not mentioned in documents after this time; in later decades, the capital of Yustaga was Cotocochuni or Potohiriba.

Nevertheless, Uzachile or Ossachile appeared on some later maps. It first appears on a 1684 map by French cartographer Jean B. L. Franquelin. As with many colonial European maps, Franquelin’s geography is warped to a fanciful degree and bears almost no relation to reality. It features such errors as mountains in the Florida Panhandle, a giant inland sea roughly at present-day Atlanta, and even real towns are placed in totally incorrect places. Case in point is Ossachile. Franquelin relocates this Panhandle town last documented 150 years earlier far to the north of the Timucua missions in the Jacksonville.

Many later maps relied on Franquelin’s. One by the Dutch publisher Pieter Van der Aa may have been the source of Frederick Davis’s faulty identification. The geography of this 1706 map manages to be even more mistaken than Franquelin’s, showing mountains in the Florida peninsula. It shows Ossachile along a river in an area that an observer could easily identify as Downtown Jacksonville, if any of it bore any relation whatsoever to genuine geography.

The theory that Doug and I propose is that while writing his book in the 1920s, T. Frederick Davis saw the van der Aa map, or one very much like it, and reasonably mistook the location of Ossachile for Downtown Jacksonville. Misreading it in “Ossachile” for “Ossachite,” he included it in his brief footnote and inadvertently sparked a legend that’s still going strong today.

The legend of Ossachite fascinates me in another way. It shows that Jaxsons have long had an urge to know more about their city’s deep past and Native American heritage that greatly exceeds the amount of authentic information available to them. Having little access to the true story of the Timucua, they seized on a myth. Myths can be good things — they can help bind people to their place, and in some cases can encourage them to seek out the truth. That was certainly true for me when I first heard of the mysterious city nearly 20 years ago.

Fortunately, folks today don’t have to rely only on myths. The explosion of research on the Timucua has led to dozens of books trying to bring new life to their culture, language and history. Check out the work of Doug and his colleagues on the Timucua language at Hebuano.com and pick up some of the many available books, a few of which are included in our list of the best books about Jacksonville. Ossachite may never has existed, but it continues to leave its mark.

Contact Bill Delaney at w.delaney@moderncities.com.

Lead image: Theodor de Bry’s engraving of a Timucua village, supposedly based on a lost painting by Fort Caroline survivor Jacques le Moyne.