Florida’s largest teachers union filed a lawsuit Thursday against the state Department of Education, in the first legal challenge of its kind over a law that critics say has led to book bans in schools.

The Florida Education Association filed what’s known as an administrative legal challenge. It’s not challenging the law itself, HB 1467, which requires schools to be transparent about curriculum and library materials and was signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis last year.

Instead, the suit says the Department of Education expanded the scope of the law and went too far when it issued training for school librarians this year.

“What has happened here is Florida officials under the DeSantis administration have flagrantly and unlawfully exceeded the quite narrow authority that HB 1467 provided the Department of Education,” said Skye Perryman, president of Democracy Forward, a non-profit legal advocacy group which has lawyers on the case.

The Duval County school district has been particularly criticized for ordering that books be removed from classroom libraries if they have not been approved. DeSantis claimed the district took a hard line to make the state look bad politically, but the district responded that it was merely following the guidance of the state Board of Education.

HB 1467, which took effect in July 2022, “requires school districts to be transparent in the selection of instructional materials and library and reading materials,” according to the text of the law.

Perryman said HB 1467 “authorized the Department of Education in Florida to prescribe how certain lists of books in libraries are formatted, and to develop specific training material for educators.”

However, two rules issued after that, known as Rules 6A-7.0715 (Training Rule) and 6A-7.0713 (Elementary School Rule) “really rewrite the law that the legislature passed last year through a rulemaking process,” Perryman added.

For one, she said the state redefined the term “school library” to include any collection of books in a school, even those in classrooms.

From the lawsuit: “While ‘Library Media Center’ is defined in H.B. 1467 or elsewhere in the Florida Statutes, the proposed Training Rule defines ‘Library Media Center’ to mean ‘any collection of books, ebooks, periodicals, and videos maintained and accessible to students on the site of a school, including classrooms.’”

That language is also heard in a training video all school media specialists in Florida have to watch. In it, a female voice says: “Elementary classroom libraries are a type of school library. Materials in all school libraries must be selected by a certified media specialist.”

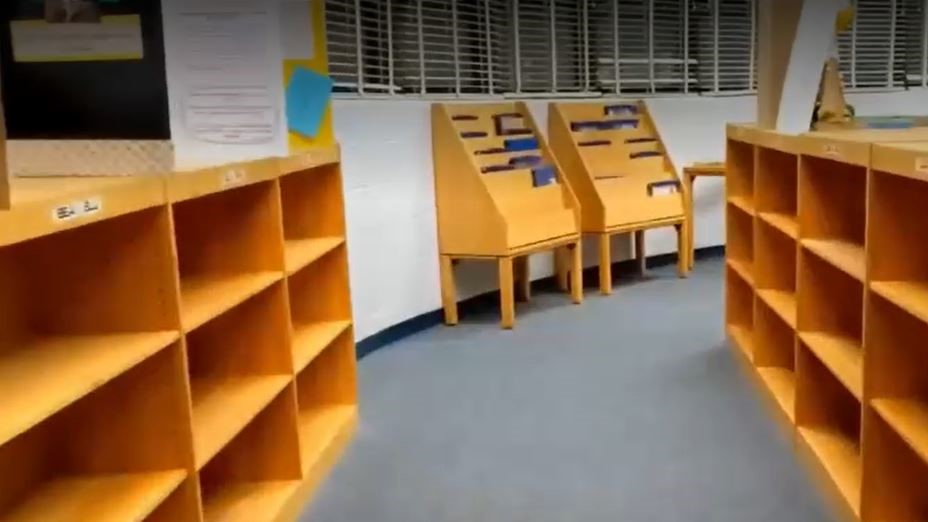

Words like these have led some teachers to empty their classroom shelves, said Andrew Spar, president of the Florida Education Association.

“We’ve all seen teachers being told to box up their classroom libraries, to take the books off the shelves and put them aside if they are not books provided by the school or district,” Spar said, adding that’s not what state lawmakers intended with HB 1467.

“When they were debating it, they took out specifically ‘classroom libraries’ so that they would not be covered by this law and the Department of Education, by rule, put it back in.”

Earlier this month, DeSantis lashed out at reports of book bans in schools, describing them as a “hoax.”

But Spar said some districts have told staff to restrict access to classroom libraries, and these are “definitely a reaction to these laws that the governor promoted and passed. And yes, books are being taken off the shelves. So the governor can call it a hoax. But we all know, based on what we’re seeing that that’s just simply not the case.”

The suit, which was filed in the state division of administrative hearings, said the Department of Education’s rules “effectively prevent most teachers from selecting materials for their own classrooms, foist uncompensated and time-consuming duties on teachers and librarians, forbid most parents from sending books to school in their children’s backpacks, and impose a costly and burdensome requirement that schools catalog nearly every book, periodical, or other media on their premises.”

It alleges that the rules “substantially harm hundreds of thousands of teachers, librarians, students, and families by upending Florida’s public education system,” and should be rolled back.

“Through new restrictions and requirements imposed through an invalid exercise of delegated legislative authority, the rules stretch beyond the statutory language and change the effect of the law by adopting an unprecedented and illogical definition of ‘library media center’ that should be struck down,” said the text of the suit.

According to Jay Wolfson, the Associate Vice President for Health Law, Policy and Safety

at the University of South Florida, “as a general rule, administrative officers of the state are presumed to be the experts in determining how statutory language is interpreted and applied.”

In an email, he said, “Hearing officers and courts historically defer to that judgement, and agency leaders are generally afforded great latitude, unless their actions are deemed arbitrary and capricious, or patently violating the plain language — and for some, the legislative intent — of the statute.”

“It will be up to the administrative hearing officer -– and then subsequently the courts, upon appeal, to determine whether the administrator has acted beyond the scope of the statutory authority contained within the language (and for some judges) the legislative intent of the law,” he added.

Any appeal “would likely proceed to the state judicial system – where it would climb the ladder to the State Supreme Court,” according to Wolfson.

The Florida Department of Education did not respond to a request for comment on the lawsuit.

The two other parties bringing the legal action along with FEA are the Florida Freedom to Read Project and Families for Strong Public Schools.

“The agency’s actions have attempted to create a divide between parents and educators,” said a statement from the Florida Freedom to Read Project.

“These new rules have removed our parental rights to allow our children to self-select their reading materials and created an unnecessary barrier to young, emerging readers. Parents, having not been heard in the board room, must now look to the law to get their power back.”

According to Perryman at Democracy Forward: “Parents and teachers and communities are mobilizing and fighting back and they’re going to use every tool in the toolbox, including legal tools in order to push back against what is a dangerous national movement.”

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))