On Friday, the tenth day of Black History Month, I picked up my son and his friend from the bus loop in our neighborhood. I asked them about school, their day, if they had fun. I dropped the friend off and proceeded on my route to pick up my daughter from daycare.

“Mom, we have to do a project,” my son says.

My ears perked up. Finally, I thought to myself, assuming the project was something centered on Black History Month.

“What’s the project about?” I asked.

He couldn’t tell me exactly. Only who he wanted to be.

“Who is that?” I asked, curious but half-listening as I navigated rush hour traffic.

“I want to be Neil Armstrong.”

“No!”

My reaction was immediate and vehement. No.

“Whyyyyy!” He whined.

“Can’t you be somebody other than a white man?”

“I can be a dollar bill,” he suggested.

“No!”

For the next hour and a half, as I picked up my daughter, returned home, put chicken nuggets and French fries in the oven, and commiserated with my own mother, my son cried.

He protested. “You won’t let me be who I want to be. You said I can be anything.”

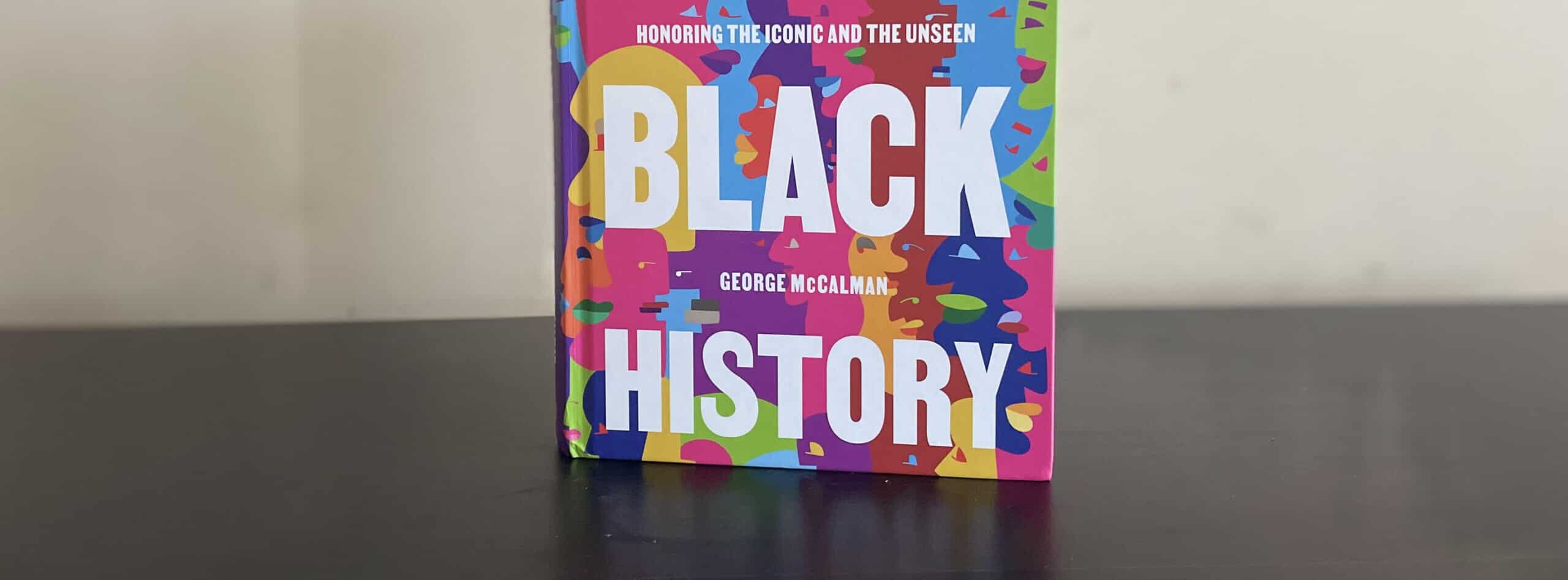

“You can be anything,” I tried, exasperated. “Anything other than a white man. I have a whole book on Black heroes with their biographies,” I said, referring to George McCalman’s opus Illustrated Black History: Honoring the Iconic and the Unseen.

I had received the book from the publisher and interviewed McCalman on my podcast. I declared during the episode that I couldn’t wait until my son had a Black History Month project and we could pick someone from the book to do as the subject. When I showed my son the book, lush with color and rich in story, he thumbed through the table of contents pages with tears running from his eyes and snot dripping down his nose, unimpressed.

“I don’t want to be Martin Luther King again,” he repeated. “I was him in kindergarten and in first grade. Why can’t I be who I want to be?”

“You can,” I emphasized. “But you’re a Black boy. Why can’t you portray someone who’s Black.”

“I want to be Neil Armstrong.”

He was adamant.

“Why can’t you be a Black astronaut?”

I quickly searched “Black astronauts” on my iPad and flung the populated Wikipedia page at my son so that he could see other representations of heroes who had gone to space other than Neil Armstrong.

“But they’re not on the list,” he said.

Yes. The list. Along with the project instructions, what came home from school was a list of possible people, places, or things the students could portray for their Living History Museum project. An assignment due in March, outside of Black History month. On this list were the usual suspects, the Washingtons (George and Martha), Abraham Lincoln, President Biden. There was also the Washington Monument, the dollar bill, the White House, and the Florida state flag. Out of the two dozen or more “possible options,” only four were Black people: Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman and Ruby Bridges.

I struggled to make adult understanding translate into kid logic. I suggested my son portray Barack Obama, because surely the first Black president of the United States is living history.

“If Joe Biden is on the list, surely you can be Barack,” I said.

More tears.

“What about the man who created the super soaker? He’s Black,” I suggested, referring to Lonnie Johnson.

More snot.

“What about the man who made the traffic lights? He’s Black,” I said, suggesting Garrett Morgan.

Furious head shake no. “I want to be Neil Armstrong.”

My son ran into his bedroom and slammed the door. I resisted yelling at him for slamming doors in my house like he paid bills. My foray into gentle parenting rearing its head at the most opportune time.

“Nikesha, let him be Neil Armstrong,” my mother said from FaceTime.

As my daughter tore apart her bookshelf with books from Vashti Harrison, creator of the Little Leaders series, my mother and I hatched a plan to let my son do a project about Neil Armstrong while also highlighting notable Black astronauts. (I went to the same high school as Mae Jamison, so she was definitely getting mentioned.)

My mother, still on FaceTime, coaxed my son out of his room and told him the plan. Reluctantly he agreed.

“Well, let me find an astronaut costume on Amazon,” I said.

The snot receded, the tears dissipated. The makings of a smile began until I realized that Neil Armstrong was one of three choices my son was to list before being assigned a final subject at the teacher’s discretion.

“Who else do you want to portray,” I asked.

“Michael Jordan or Lebron James.”

I rolled my eyes so hard I wished they had gotten stuck.

Monday, I messaged my son’s teacher and asked that he be given Neil Armstrong for his project, explaining that there were only four Black people on the possible choices list and three of them were women. She agreed to Neil Armstrong and the plan to incorporate Black astronauts into the project.

African American studies, Indigenous studies, queer history, A.A.P.I. studies, Latin heritage, women’s history, feminist literature, womanist theology, all of these rigorous academic subjects that inspire critical thinking and an examination of the roles and influence of patriarchy and white supremacy, are necessary, if for no other reason than for parents who identify as one or many of the aforementioned “minorities” have an easier time convincing their children to take pride in the contributions of people who look like them that may not always make a suggested list of heroes for a school project.

Nikesha Elise Williams is an Emmy-winning TV producer, award-winning novelist (Beyond Bourbon Street and Four Women) and the host/producer of the Black & Published podcast. Her bylines include The Washington Post, ESSENCE, and Vox. She lives in Jacksonville with her family.